August Kranti Day, this week, is time to explore the paths around Gowalia Tank’s historic maidan

Salahuddin Kallan

It happened over two days 74 monsoons ago. Cries of “Quit India” ripped the air thick with freedom fervour on August 8 and 9, 1942. History was in the making on the gulmohur-laced Gowalia Tank green, soon to be christened August Kranti Maidan. Aruna Asaf Ali hoisted the Congress flag, political heroes marched to their arrest and teargas released for the first time in the country.

It happened over two days 74 monsoons ago. Cries of “Quit India” ripped the air thick with freedom fervour on August 8 and 9, 1942. History was in the making on the gulmohur-laced Gowalia Tank green, soon to be christened August Kranti Maidan. Aruna Asaf Ali hoisted the Congress flag, political heroes marched to their arrest and teargas released for the first time in the country.

Shells fell in dark drifts around Malati Jhaveri. The collegian defiantly lobbed a piece back at a British soldier. Draped in a red khadi sari she was whisked off to jail, where her patriotic songs won police sympathy too. Before she died in 2014, Malatiben related the incident to me, kohl-lined eyes flashing. She thought she had risked the wrath of her silk merchant father, who was Sheriff of Bombay and had been knighted three months earlier in May 1942. “He was Sir Shantidas Askuran, yet so nationalistic, telling me, ‘I’m your pita but you must follow your Rashtrapita, Gandhiji’.”

ADVERTISEMENT

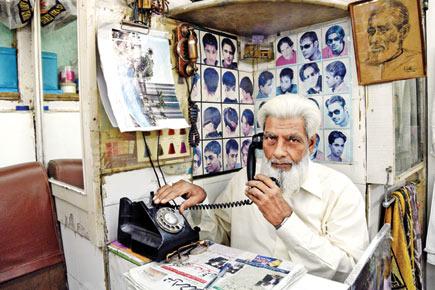

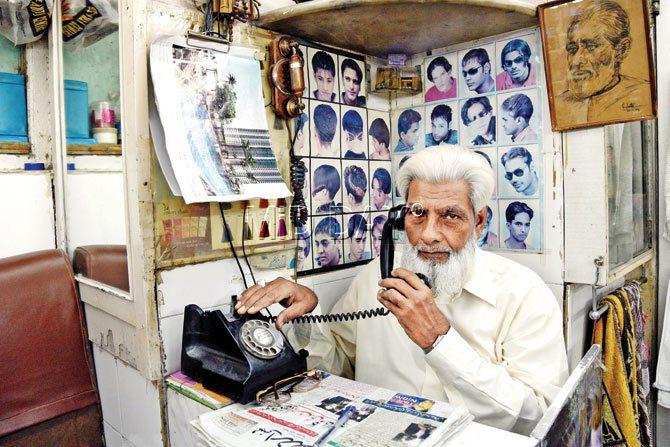

Salahuddin Kallan at Royal Hair Dressers, set up in 1925 by his father Kifayatullah Kallan (seen in the charcoal portrait). Pic/Suresh KK

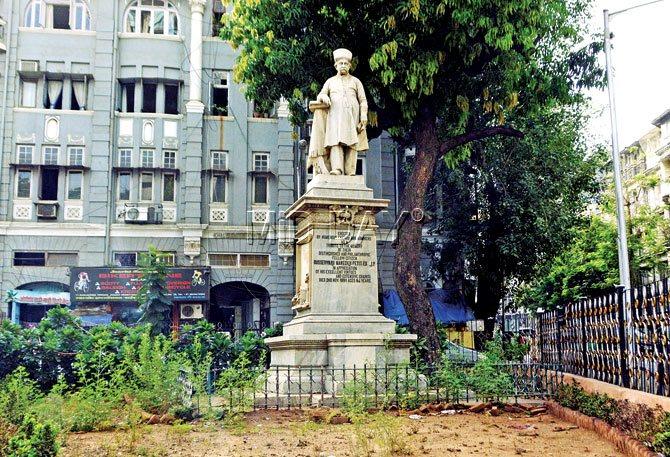

Bare metres from the maidan milling with impassioned pleas for independence, a young wife watched from the second storey of Khaluckdina Terrace, within a whisper of Gowalia Tank (its name has a bucolic allusion: “gow” meaning “cow”, Gowalia referred to shepherds bathing cattle in the boat-filled tank). Now over a hundred, Villie Unwalla gazes out from that same window since her marriage in 1936. The statue of philanthropist NM Petit, clad in traditional dagli coat, stands below. Looking past it at the maidan, reliving those hours, she says, “Hearing shouts of ‘Do or Die’ we felt such a sense of pride.”

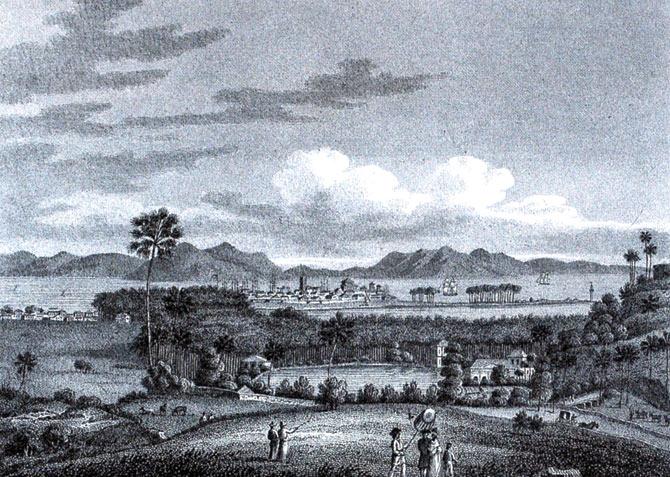

A view of Gowalia Tank Road in the foreground of this 1771 painting by J Storer. Once a wilderness, rice and pomelo plantations came to be cultivated on this stretch before it began to be built over. In the late 1800s a tiger was sighted prowling down from Malabar Hill to drink from the waters of this tank. PIC/COURTESY “Bombay to Mumbai: Changing Perspectives”, Marg Publications, 1997

Two years later, in April 1944, the Unwallas were stunned by another deafening echo. World War II’s explosion on the steamship Fort Stikine flung debris way beyond the docks. A gold brick flew a thousand yards, landing in their flat. “We felt the impact because it was all quiet for miles,” she says. It was more silent still at the turn of the century, when her in-laws would spot only one car every hour. “People mostly pedalled cycles they polished with pomade. And our corner was the terminus where trams changed wires.”

The statue of philanthropist N M Petit stands outside Khaluckdina Terrace at Gowalia Tank. Pic/Bipin Kokate

Rumi Taraporevala, her neighbour in the Soonaiji Agiary lane opposite, rode a pair of routes. Boarding tram Number 13 or 16, he jumped off at Charni Road junction for another to Dhobi Talao’s St Xavier’s School. “Conductors clanged that bell underfoot and I indulged in some thuggery,” he confesses. “Kids up to 9 years travelled for half an anna (2 paise). Being small-built I got away till finishing school at 16! Speaking of which, my father gave his matriculation exam around 1918 sitting under a mandap in this maidan.”

Trundling to Bori Bunder and the Museum via Pila (Play) House in Grant Road’s theatre district, Number 16 passengers would wave at familiar faces. Their phoolwalla stringing rose petals for fragrant door torans. Their fruitwalla pleased to have a patron in JRD Tata’s wife, Thelma, coming in a Chrysler from Altamount Road to pick juicy piles. Their widest smiles must have been for the andawalla, or egg man, numero uno surely with the Parsi community’s penchant for “eeda” over everything edible.

Growing up in the serene cul-de-sac ending at Soonaiji Agiary, solicitor Kaiwan Kalyaniwalla notices Bohris and Jains swell the demographic pool. A small miracle shines at the agiary celebrating its 204th anniversary this week: natural veins ingrained in marble walls form the face of Zoroaster, from the paghri on the prophet’s head to his flowing beard. The agiary has one of seven interconnected wells. Others include those in Jer Mansion, Khaluckdina Terrace and Tejpal Theatre. There are stories of spirits in these wells — the one at Khaluckdina, a servant reported, assumed the benign shape of a white kite.

Flanked by buildings with beautiful balconies and balustrades, the gully is also home to chocolate queen Meher Pinto, the Iranis of Wibs Bread and generations of cherubic children playing Chor-Police between tightly parked cars. Back then, horse tongas circled the compound’s only private vehicle, the 1927 Ford Model T of Behramsa, father of Taj hotel architect Rusi Patel.

Taraporevala would wake from nightmares as a child in Cozy Building, calmed by the reassuring clop of bullock carts. “There was a 24-hour service for taxis too,” he recalls. “They gleamed under gas lamps lit by slim, wiry men like long-distance runners in khaki shorts.” His elegant wife Freny glances around their terrace spilling with bougainvillea and money plants glossy from recent rain. “This is my favourite spot,” she says simply. The couple’s photographer-filmmaker daughter Sooni adds, “You could walk our lane on fixed nights to hear Adi and Silla Marzban’s voices booming from a radio in every flat. I had one eye on the clock, willing it to go slower, but inevitably the half hour of their play would be up.”

Sooni has joined us to record her dad’s reminiscences. He’s returned from a trim at Royal Hair Dressers. Visiting this 1925-established salon of Salahuddin Kallan next afternoon, I find it superbly frozen in time. Ten men slumped in ancient barber chairs struggle to straighten as I enter. “Madam yeh gents ka hai,” murmurs one before realising it’s a chat, not a cut I’m after.

A step from Royal is Ideal Restaurant where Nizam Dhukka feeds customers mutton masala fry, kheema and omelette pav for close to fifty years. Old-timers miss the Oriental Restaurant and Stores — part Irani café, part pharmacy; it is Grand Centre today. Dick Joice sold medicines and liquor from different entrances. Nipra was the chemist delivering home. Star Bakery’s chocolate-topped cream cakes went for an anna each. Manhar offered toast and batasa biscuits sealed hot in steel tins and wide-mouthed jars; glass covers with electric bulbs ensured these savouries stayed crisp.

The shop front hiding a tragedy is My Own Studio at Sheridan House.

Its proprietor Rajesh Mistry explains how their wing of the building collapsed in 1965. With five floors crashing, his father could not escape being wedged between his counter and the dentist’s chair of Dr Pesi Nanavati that tumbled from upstairs. The good doctor’s neighbour, journalist Amy Fernandes, knew something was wrong the moment her father unusually showed up at Villa Theresa Convent to escort her home. Hutoxi Hodiwala’s grandmother went down four floors in her bed. She survived, as did the flame of the little oil lamp she had lit. That it continued to burn on the prayer table till evening was viewed as an act of faith. The family’s pet parrot dropped with his cage, shaken. Sensing disaster, the African Grey had squawked a prescient, plaintive keh-keh-keh refrain through that fateful morning.

Happier sounds I try re-imagining, over the hellish honk of present traffic, are cries of street hawkers Gowalia Tank veterans describe. Jari purana wallas and knife sharpeners roamed with basket vendors peddling topli paneer. Not forgetting kaleji bheja sellers whose liver and brain delicacies thrilled meat eaters.

On reaching Hardinge House, I see it rudely razed. A redeveloper’s board cockily girdles the property. This was home to Firoz Bardi, now in Pune, who admits to “pangs of pain on passing it”. Tehmina, daughter of their neighbour Shirin Daruwalla, became maestro Zubin Mehta’s mother. Bardi saw a shy Zubin often come to meet his grandparents in the 1940s.

In the flat above were the Contractors, related to dashing Farrokh Engineer who, to Bardi’s delight, obliged with a cricket game in one of the rooms. Bardi has a horrifying schoolboy memory of Gowalia Tank’s brush with the underworld — a bloodied goonda knifed in the stomach had once lurched towards him on this road.

A short hop away, an eatery marks the maidan’s east edge. Seeming to take quite seriously the watery antecedents of the area, its piquant tagline advertises: “Lagoon: a lake of tasty food”.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at mehermarfatia@gmail.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!