Pune’s industrial thrust stumbles over religious sentiment as a hill that locals hold more dear than economic opportunity sits at the centre of controversy

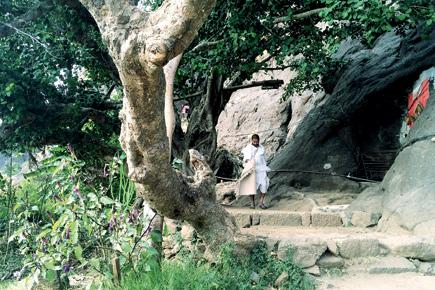

A monk outside his cave at Bhamchandra Hill on the Pune-Nasik Highway.

Bhamchandra Dongar, 35 kms from Pune sits steady and calm but is at the centre of a controversy raging around it. To locals of Dehu, and the surrounding villages of Shinde, Vasuli and Bhamboli, the hill is one of three tekris that 17th century poet-saint, Tukaram or Tukoba, as he is colloquially known, took refuge at to ponder the mysteries of life, god and the universe.

ADVERTISEMENT

A monk outside his cave at Bhamchandra Hill on the Pune-Nasik Highway. Pics/Mitali Parekh

The migrants who work in factories that populate the industrial complex of MIDC Chakan Phase II at its foothill; and the sahibs who drive their BMWs, Dusters and Mercs on the wide, clear roads into these factories are vaguely aware of a holy hill where Varkari students reside. Teachers of Vasuli's public school who walk to the hill during their free periods, complain that the single, lonely immigrant doesn't understand the historical and spiritual gravitas of the site and go up to drink and make-out. The valley around it grows onions, potatoes, groundnuts, bajra and jowar, but relies on temperamental rain for irrigation.

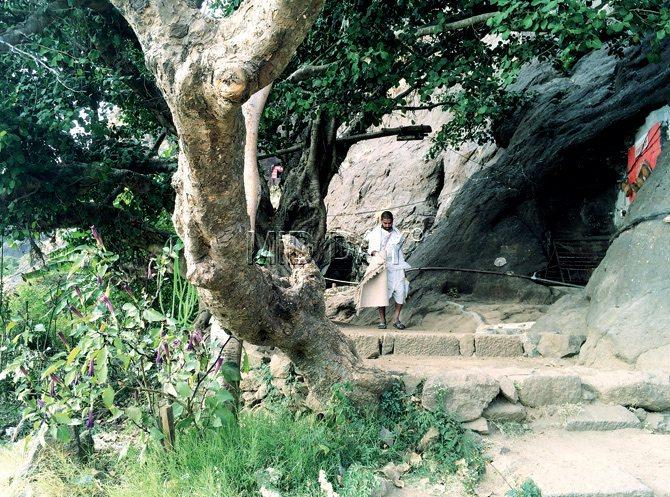

The Shiva temple mid-way up Bhamchandra

Farmers already disgruntled over the forced land acquisition for industry by the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) in 2009-10 were further miffed when in 2011, Chinese automobile firm Beiqi Foton Motor Co., the country's largest truck maker, stepped into the argument by buying 270 acres right under Bhamchandra. A clash of interests was imminent.

The gate to the Foton property below the approach road to the hill

So careful is Foton about not making a wrong move that you cannot get past the receptionist at their Pune office. "We have no comments on the matter," is the statement given. No press officer or spokesperson is named. Even trade reports of the company in industry papers are carried without a comment from the head of operations in India, Xu Xinsheng.

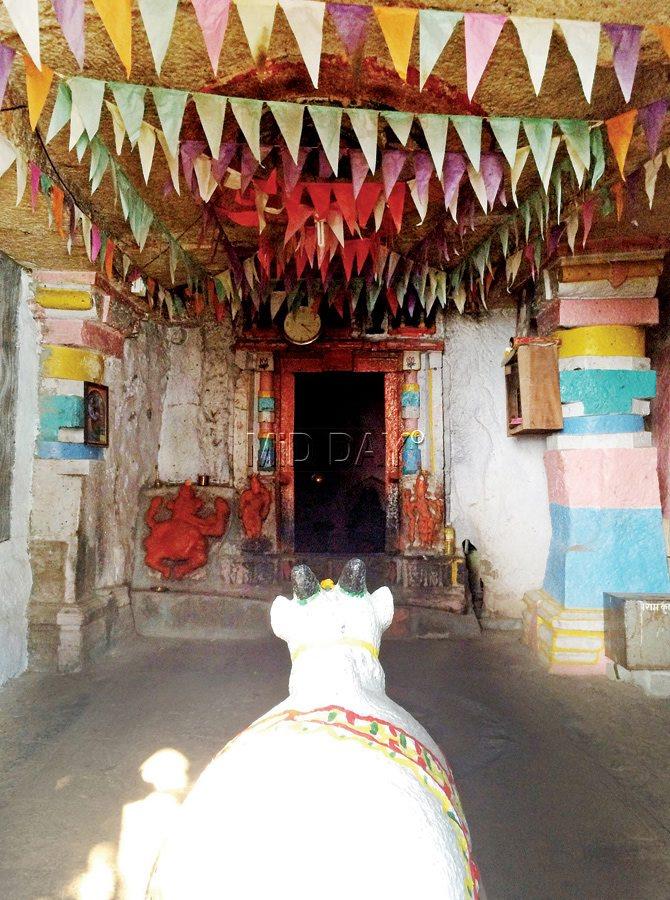

With the shrinking of farmland, the Thakkar community of farm labourers are reluctantly readying to take up jobs as construction labourers

While there are several more firms, including Tetra Pak, Schindler, GE and Air Cell, that have bought land around the hill, Foton feels the heat because its land is located right under the tekri. But MIDC CEO Bhushan Gagrani maintains that the prescribed distance from the heritage site has been maintained (regulations ensure a 500m distance between temples and construction sites).

Land owners like Sunil Ghanwat, who sold their ancestral land to firms like Foton, have built opulent homes and launched small businesses

Foton's land has been split into two — 200 acres on one side and 70 on the other, to leave alone the Maruti temple where Tukaram would first pay obeisance before climbing up to the caves on Bhamchandra to meditate.

The temple is also the site of the annual Saptahi, a week-long event when hundreds of Varkaris camp at the foothills to chant and sing day and night in praise of their lord, Vithoba. The neighbouring villages take turns feeding them. There was talk that Foton had an eye on this patch too, but Gangrani says Foton surrendered the 70-acre patch and requested MIDC to provide a compensatory area close-by. "They need an additional 1,000 to 1,500 acres of land for an industrial park," says Gangrani, "But that will not be possible in Chakan because we don't have that large a plot. We have shown them sites in Nagpur, Nashik, Nanded and Aurangabad. They are yet to finalise one."

Activist Madhusudan Patil is fighting to convince the government to declare the hills as eco-sensitive zones and a heritage site. Pic/Dattatraya Adhalge

Though cordoned by a barbed wire, Foton's plot sees no gate to bar shepherds from roaming into the bit of land closer to Vasuli. The other patch, nearer Shinde, has a security cabin and guards to question those who wander there.

Inequal returns

The villagers are not convinced that their sentiments will be respected. Those that sold the land to MIDC, including Arjun Panmand and the Ghanwat family, received Rs 16 lakh per acre. Their houses are the most recognised in the village — two and three storey bungalows with brightly painted balustraded balconies.

Sunil Dutt Ghanwat's family gave up 20 acres of ancestral farmland near the hill. The leftover, they continue to farm on. But the money flows in from their water tanker business. "My son is studying to be a mechanical engineer and my daughter is giving her UPSC exams. We hope these companies [at the foothills] will give them jobs once they finish their studies," he says. He also has livestock — goat, bullock and cows for a diary business.

Panmand's family gave up 32 acres, and like the Ghanwats, invested in tankers. He has enough farmland to sustain the family and is currently rejoicing in a good harvest of onions. It's the Thakkar community of adivasis, who work as farm hands and lease farmers, whose future hangs in peril.

"They are not educated and work at the rate of Rs 300 a day at the farm; or on a sharing basis through the year," says Panmand. "In that case, we provide the seeds, water and land, while they put in the labour. After harvest, they get half the yield's profit. The Thakkars live in Thakkarwadis off the villages. They rely on the forest for food — hunting, gathering, collecting firewood."

When factories come, the Thakkars could be employed as daily wage construction labourers, gardeners and housekeeping staff, and if they are skilled, as drivers or machine operators.

Would they like that? It's a stupid question.

Shankar's silence says so as he picks onions while Panmand oversees the harvest. "If we have no choice, it's what we will do."

The Thakkars are a guarded lot. They don't want to be photographed, they don't like to give their names and they don't want to get into a stand-off between current employer and potential employer. They have no powers and this is not their fight. As farm labourers, payment is dependent on nature and the landowner's benevolence. As factory hands, it will be more systematic and with benefits, but they will be dispensable labour.

Monks are protectors

Up on Bhamchandra, things are simpler.

There is first the Maruti temple. Then mid-way, there are a few caves that house a Shiva temple. And right at the top is a Vithoba mandir (an avatar of Vishnu the Maharashtrians revere) and his consort, Rukmini. There is a motorable road that goes right to the top, taking about two hours. And a steep footpath that takes you to the mid-level in 20 minutes and very short breaths.

It is somewhere here that Sant Tukaram was visited by his Pandurang (Vithoba) on the 15th day of meditation. In the mid-level caves is now a small housing arrangement for monks from the Varkari sect of Alandi.

Yashwant Chaukhandi is one 12 monks who live here. He has piercing amber eyes crowned by three sandalwood stripes.

Originally from Amravati, he studied in Alandi for four years and now lives here to learn by rote, the works of Tukaram, Dyaneshwar and other minstrel saints of Maharashtra. Their sustenance comes from the villages below where they seek bheeksha.

"It's calm up here, and quiet," says Chaukhandi, who looks like he could be in his 20s. "We feel closer to Tukaram. They say when Tukaram's second wife Jijatai would set out to take him his lunch from Dehu, she wouldn't know which hill he was on. He told her to put her ear to the ground and follow the path on which she heard, 'Vitthal, Vitthal... We feel this earth still resonates the chant." Does the creeping industrialisation bother them? "As long as they don't touch the mountain, we won't do anything. If they do, there are many of us to protect our bhakti dham," he says calmly and refuses to be photographed.

Local activist Madhusudan Patil wishes the one-and-a-half lakh Varkaris would do more than just wait. With his anger, he is trying to move mountains. "I belong to no religion. I am only and simply a Tukaram bhakt," he says. Patil has been petitioning the zilla parishad to declare Bhamchandra as a heritage site and eco-sensitive zone. "I'm planning to move court," he says determined.

Local legend has it that Patil has been visited by Pandurang on Bhamchandra. Cheeky locals also send nosey tourists to him in Pune when they get irritating. "It is ironic that the poet who preached about respecting the ecology and nature should be crowded by smoke," he says. "Both hills — Bhandara and Bhamchandra — have been recognised even in the British gazettes for their cultural and religious importance. The government should push for them to be recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Even if the industries are built beyond a prescribed buffer zone, won't the air and water pollution affect the ecosystem on the hill?"

Assistant Director of the Pune division of the State Directorate of Archeology and Museums, Vilas Wahane clarifies the hill's status, saying that under the Ancient Monument and Archeological Sites and Remains Act of 1960, the first step to declare the Bhandara hill as a state protected monument was taken in 2011. A notification was published in the Maharashtra State Gazette and a copy of it posted near the site giving those with farmland and industries around the area two months to voice their objections. "The original plan protected the caves, the hills and some surrounding farmland, forested land and industrial land. There were concerns raised by those owning land in the foothills and a new plan was made to include only the hill, the caves and 50 mts of the surrounding area. This was submitted to the Mantralaya through the deputy secretary of the Culture Department. However, following a protest led by Patil, asking for the plan to be reverted to the original one, the matter is under contention."

If Patil succeeds, not just Foton, all other industries around will have to take the hit for polluting the environment. Gangrani has a more pragmatic approach, "In India, there will always be something of cultural importance close-by. Development cannot happen like this [if we keep away from all cultural, historical or religious site]."

The pundits who perform the rites at the temples on Bhamchandra come and go to their 'maaher' (mother's home) to meet 'Mauli' (their mother, Vithoba). The terms with which they address the saints, gods and their consorts are familiar, as if they are family members — Vithoba, Tukoba, Mauli. They are not overtly reverential as when addressing a distant divinity.

The egalitarian lord

Vithoba is a part of daily life. He helped Janabai, another poet-saint, with her housework. "Tukaram's poetry is important because it is original," says Pandurang Balkawade, a historian and researcher. "It is not a retelling of the Vedas or the Bhaagvat. It is part social and political commentary; part advice; part devotional praise and part simplification of man's relationship with the universe. It's told in a simple tongue, not in Brahmanical Sanskrit. And the Varkari sect is egalitarian, not confined to caste division. People look for solace from daily strife in the abhangs [poem sung in Vithoba's praise]. It sent the message that devotion to God didn't have to go through the priestly class."

And what does he think of the industrial imposition on the hill?

"Bhamchandra and Bhandara are sacred land and respect for them should come from the people visiting," he says. "You should know that this is not the place to drink or party with friends, or take your girlfriend to. You can do that 10 km away in Mahabaleshwar or Lonavla. This is a place where one should retrospect and meditate. The land below is a famine-prone area. Industries will bring livelihood. Tuka would not oppose this." In the caves at the tallest level on Bhamchandra sits a monk who has not spoken for 26 years. Nobody knows his name or why he has taken the vow of silence. No one knows what he will do if peace on the hill is broken.

"Like Jijatai," says a school teacher, who is out for a walk, "he only hears Vitthal... Vitthal..."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!