Ahead of the State of Architecture exhibition, curators Rahul Mehrotra, Ranjit Hoskote and Kaiwan Mehta get chatty about smart cities, heritage, and of course, Bombay

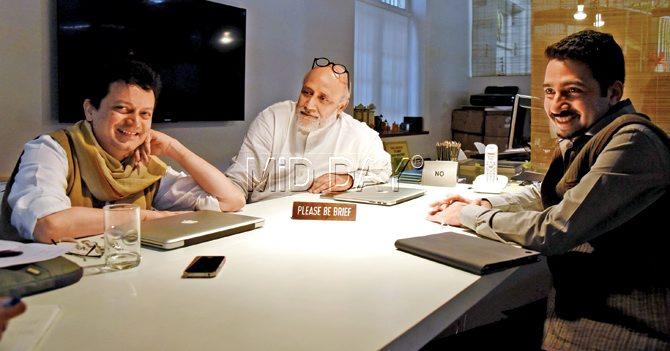

(From left) Cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote, architect Rahul Mehrotra and architecture theorist Kaiwan Mehta.

To define the upcoming State of Architecture exhibition, its curators start with what it isn’t. It’s not the “sexy kind of exhibition” where you will find the “starchitects”. It’s not sponsored by realty developers or the one that happens in exotic destinations. Taking a sweeping shot at contemporary architectural practices in the country, and helmed by architecture theorist Kaiwan Mehta, cultural theorist and poet Ranjit Hoskote, and acclaimed architect Rahul Mehrotra, it will have an old-school rootedness (the Charles Correa variety) that pays attention to what’s around you.

ADVERTISEMENT

Cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote, architect Rahul Mehrotra and architecture theorist Kaiwan Mehta. Pic/Suresh KK

Starting on January 6 and stretching up to March 20, the exhibition, presented jointly by the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Mumbai, and the Urban Design and Research Institute (UDRI), will see satellite exhibitions as well as a South Asia-level

conference.

Rahul Mehrotra. Architect

In the past week, the exhibition team, which includes Kamalika Bose, Riddhi Shah, Sohil Soni, Zenia Vandrewala and Jemma Antia, has been settling upon the colour of the walls and the typography for the exhibition. But these are secondary to what the team discusses on a daily basis — the meaning of ‘architecture’. “We wanted to bring the focus on architecture without losing it in the conversation about conservation, monuments, cities, infrastructure and so on,” says Mehta. The city, he adds, is not the only way to talk about architecture. As we settle down around a table surrounded by miniature architectural models in Mehrotra’s Kala Ghoda office, the architect asks, “So, can we dive straight in?”

Ranjit Hoskote. Cultural theorist and poet.

Q. A favourite frequent grouse of most Mumbaikars — that civic buildings are an eyesore, and public structures, unaesthetic.

Rahul Mehrotra: When India got Independence, the nation-state used architecture to define its image and identity, which is why [Le] Corbusier came for Chandigarh. That has gone out completely. As they say, now it’s an architecture of GDP, a statistical architecture. It has nothing to do with form because the identity of nations is now in accordance with growth rates. The state has absolved itself of identifying itself through art and architecture and doesn’t commission architects any longer; you have to then rely on Mr Ambani for the iconicity. So, in the exhibition, we are not talking about farmhouses or weekend houses. That is the architect’s role in one per cent of the population. The question we are raising is, ‘Does architecture matter to society in terms of public buildings and public infrastructure?’

Kaiwan Mehta: We forget that architecture is primarily an economic activity. Whether it’s a building for a call centre, or a range of different people working, a certain economics governs the question of design. Architecture is stuck between the idea of design and the practicalities of economics.

Ranjit Hoskote: We are also presenting the exhibition as an argument against what seem to be panaceas. In recent times, we have heard a great deal about the ‘smart city’ as a solution. The smart city is not an answer to where 850 million people will be housed in Indian cities in 2050. It’s an answer to an unspecified question.

Kaiwan Mehta. Art theorist

Q. You, Mr Mehrotra, had in an interview earlier this year debated smart cities.

RM: The interview’s headline said I have no idea what a smart city is. It was part of a longer sentence that was clipped quite cleverly.

Q. What you meant was perhaps there are other ways of looking at it…

RM: Yes. The one big advantage of the smart city was that it brought attention to cities. Having done that, how we approach the problem needs more deliberation. Smart cities were invented by tech companies like IBM and CISCO at the height of the American recession because they had to sell their wares. And some dictatorships, like Singapore, picked them up. It’s a branding exercise which has been sold to our Prime Minister. Indian cities are much more complex and plural, and the danger that stares you in the face is that they will become gated communities. Mehrotra fishes out a YouTube video, uploaded by Narendra Modi in January 2013 called the GIFT City Film. The vision to transform Gandhi Nagar into a futuristic city is supplemented with a masculine Siri-like voice and a disciplined urbanscape. Among its promises are drinking water from every tap, and an underground system in place of service lanes. The smart city is like an office park, with absolutely no talk of housing, observes Mehrotra. Both Hoskote and Mehta concur that the video evokes Fritz Lang’s 1927 film on a doomed city called Metropolis. “Where is the Batmobile?” Hoskote asks.

RH: Old-fashioned as it seems, there are some Utopian ideas of what this country’s future can be.

KM: Most newspapers have a city page and weekly columns, say on books, films or food, but there is none on architecture. There is writing about heritage, but not architecture.

RH: What has happened in due course is that heritage has become an adjective in itself. (Looks at Mehrotra) You remember that joke when you were on the heritage panel ?

RM: A developer said he had made this building, and had put some arches in it, and argued with me, “Maine toh usme heritage dal diya na (I have put heritage in it, haven’t I?)” Heritage was something you could buy and put in a building. It was an aspirin.

KM: Back then, the heritage committee would hold a public meeting every third or fourth year.

Q. The current heritage committee doesn’t have any heritage experts on it.

RM: That’s the case with everything here. The value on professionalism has diminished in our society. So, a simple way of saying it, is that there is political interference in everything. Like someone said, the fact that we have bad air and bad water is actually because of corruption. We don’t implement pollution laws since people are corrupt.

Q. But, local politics and the city have changed quite a bit. Bombay is now Mumbai. Are we holding on too dearly

to the myth of Bombay?

RH: It wasn’t a myth; it was an ideal. There is a difference. For all of us, the June 1965 issue of Marg magazine is

of importance, where Charles Correa, Pravina Mehta and Shirish Patel proposed the pragmatic idea of a new Bombay. At this point, Mehrotra sneaks in a wooden wedge bearing the words ‘Please be brief’. Some brief chuckles later, Hoskote is warned not to take cues from this.

RH: All of these people felt they were stakeholders in a debate that concerned the public at large. Today, there is a kind of technocracy that believes it has all the right ideas. A large number of people, including the intelligentsia, feel excluded from this process now.

KM: As a student, I remember, I could ask someone on the heritage committee a question about architecture or the city.

Q. What, according to each of you, are the city’s most pressing issues?

RM: For me, it would be housing. And related to housing is sanitation.

KM: The relationship between education, policymaking and intellectual interaction is what the social fabric of the city needs.

RH: Housing, again. You cannot have a great city built on a foundation of inequity. You can’t have a great city where more than 50 per cent of the population lives in shanty-towns, informal housing and what I particularly object to is this romantic fetishisation of slums — the Dharavi Syndrome. It may sound old-fashioned, but I think there is a place for a plan that provides social housing. You can’t have these kinds of outrageous land prices that doesn’t allow people to have what should be the structure of a meaningful life.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!