Increasing violence and strife have made people wary of the unknown. Now, a unique project aims to prove that sometimes there is comfort not just in the familiar but the unfamiliar too, through chance, happy encounters

On that fateful morning of November 15, 2013, Munira Chendwankar had on a T-shirt that said, ‘Tendulkar No 10’ to pay homage to Sachin Tendulkar, who was playing his final Test match that day.

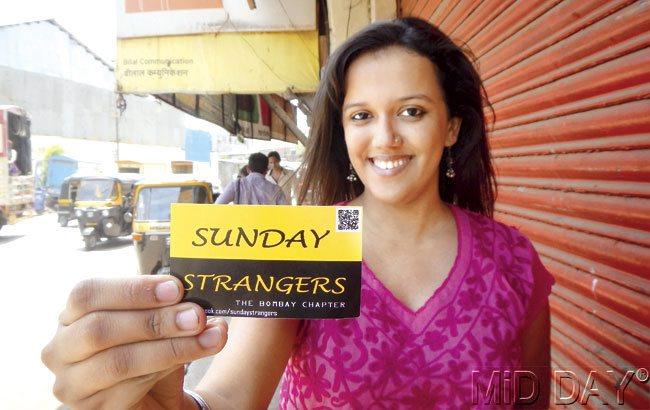

Munira Chendwankar smiles as she holds the ‘Sunday Strangers’ card. Pics/Suresh KK

ADVERTISEMENT

Having left the green, up-market housing complex in Borivali, where she lived, the toothily grinning 23-year-old Chendwankar waited at the chowk for an autorickshaw ride to work.

Bonding over Sachin

As Chendwankar stood on the crossroads, her T-shirt caught the eye of an elderly stranger, Arvind R Bhavsar, standing nearby with his grandson clutched in his arms. Her open vibe and her benign expression stirred something in him.

Shakti Mills, the site of the Mumbai gang rape. Pic/Sayed Sameer Abedi

He too was a diehard Sachin fan, he told her; he had seen Tendulkar play for his school, Shardashram Vidyamandir, at Brabourne stadium against Anjuman-i-Islam, in 1987. What a day! His batting had impressed Bhavsar, who had bunked work to see Tendulkar play, so much so that he’d gone and told the boy some day you will surely play for India.

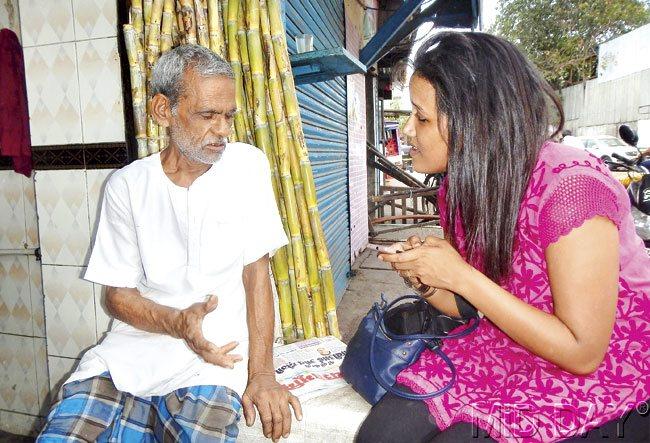

Chendwankar talks to a stranger as part of her project

Fast-forward: when the grown-up, much-feted Tendulkar was visiting the Taj Hotel, Bhavsar’s son was manager there. The elderly man met Tendulkar again. He reminded the master blaster of their previous meeting. Hearing this, Tendulkar thanked him for having believed in him even then. Bhavsar recounted this soft, warm anecdote to Chendwankar and smiled.

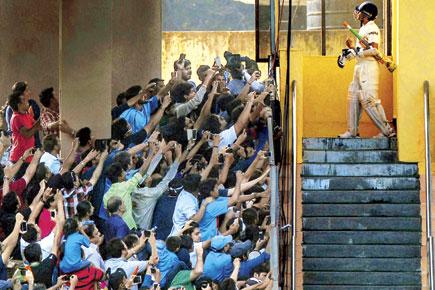

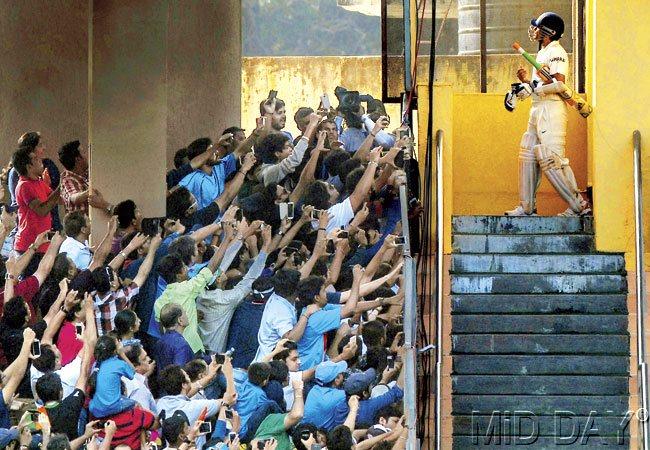

Sachin Tendulkar during his last Test, a chapter in Chendwankar’s Sunday Strangers story. Pic/Atul Kamble

Chendwankar went on to make a connection with a stranger. She told him about herself, just the broad details about her job as a reality television producer, and said, “I also have a Facebook page ‘Sunday Strangers’, where I write about chance happy encounters. Can I click your photo and write a post about you?”

Bhavsar’s anecdote became post number 62 on her Facebook page. In March, Chendwankar wrote about her 100th stranger, having spoken with some 300 people on the road, and indirectly with thousands of Mumbai-based Facebook members.

Acts of kindness

Chendwankar’s project celebrates trust and openness on city streets. It tries to allay the mostly justified fears of women in the city. Two searing stories of rape jarred Mumbaikars’ faith in humanity. One, the Delhi gang-rape in December 2012 and then, the Mumbai gang-rape in a disused mill in the city in August 2013.

The readership was already incensed by inflation and scams, now it became outraged as well. Soon, city artists were bringing out works of anguished art and theatre — one play on rape was sponsored by a media house — with the idea that the city was essentially hostile to women, and adding that all public spaces were hostile to women.

Unlike art-as-outrage, Chendwankar’s project takes into account the routine acts of kindness by strangers that go unnoticed in the daily slipstream or even just the peaceful, benignly neglectful co-occupation of urban spaces with strangers which are the norm.

In June 2013, two months before the Shakti Mills rape, Chendwankar saw a kadaklakshmi. a mystic Hindu beggar who flagellates himself with a coir or hemp whip, on the street outside her building, and she ran down to ask him what his idea of happiness was.

Chendwankar, who was then thinking about happiness through writing as an adjunct to her TV job, recalls him telling her, “Feeding my family brings me happiness.” She says she went on a spate of meetings with around 40 strangers that day. She launched herself as a would-be-writer with ‘Sunday Strangers’ on the same day.

She says, “I am still a kid at heart. I think like a child. Some of my friends are so awkward (speaking to strangers). Some of them ask me, ‘Are you going to talk to him?’” Well, why does Chendwankar do it? “It’s fun. It’s good to try.”

Meeting new people

She says, “(To meet a stranger is like) someone throwing a dart at you, some stranger can really tell you something important. For instance this old man, Ashwin, had lost his wife some years ago, and today he paints and sings.

He sang with Johnny Lever once. He told me that it’s okay to let people go. You have to move on in life.” When news of the Shakti Mills rape in Mumbai filled the airwaves, Ashwin rang up again to ask if she was okay. At a mall near her office, she saw a young couple with a boy. “They went to a bookstore to refresh themselves with a book. He was Neeraj (last name withheld). I told them, I do this page, and I’d like to talk to you guys.”

So she waited for them to finish shopping and come out, and then she had them pose for a picture. “Earlier, their life was different but a baby completely changes your life. Their child has shown them what happiness is all about,” she says. “It’s my way of spreading happiness. I learn from strangers, and they feel happy to share their stories,” she says.

Just like a child

Sitting in their tastefully decorated flat, her mother Meena, 54, says Munira was trusting of strangers ever since she was a child. “We have a saying in Marathi: mulaache paay palanyat distat (The child is the father of the man),” says her mother.

When Munira was two-and-a-half, the family went on a vacation to Matheran, a hill station near Mumbai. The family was relaxing in their hotel one evening, when they saw that Munira was missing; they went to look for her. The toddler was in a clearing on the hotel grounds, dancing with four young men in their 20s. Her father Deepak took a picture on his analog camera. Munira keeps a copy of the photo on her cellphone.

“Sometimes,” says Deepak, 60, “she’ll spot someone interesting down on the street below our building and talk to them. Then she’ll call out to me to come down with her camera. Sometimes the neighbours ask, why does your daughter speak to strangers? I say, it’s for a project of hers.” The low-rise housing society where they live is middle-class, and typically wary of strangers.

Being the father of a girl, and given that they hail from a mainstream Marathi background, Deepak’s radar is always up, and he doesn’t quite know what to make of his daughter’s project, or of her late hours. “Sometimes, she comes home (from work) at 3 am. I am still awake. I am worried until she opens the main gate, takes the stairs and comes home.”

Her mother adds, “People say how come she just talks to strangers. But we are open by nature. When we take a rickshaw, we are curious about the man driving it. When we go to a hotel, we talk to the other people there.” Munira reassures her parents, saying that she is particular, that she is careful about whom she speaks to, and that she won’t let anyone take advantage of her. She keeps pepper spray in her purse as a safeguard.

Fear of the unknown

Many strangers, she says, look more dangerous than they are. Like, for instance, a rickshaw driver, Don (last name withheld) whom she encountered last year. When she was coming home from work late at night, there were no rickshaws near the office — just Don with a creepy stare, his rickshaw with the slogans, ‘No pyaar only yaar’ and ‘No life without wife’.

As any woman knows, a rickshaw’s over-the-shoulder-view mirror is strictly for ogling purposes — and Don’s mirror had a sticker in the shape of pouting red lips. The overall vibe coming off him unnerved Chendwankar. To make matters worse, Don told her, “I don’t give rides to just anyone.” She recalls being nervous as his meter went down.

He told her about his interests, which included the stock market and Facebook. He also gave her his view on marriage (arranged marriages: good, love marriages: unstable). When she asked him to smile for a photo, he said, “You are the first girl for whom I have smiled.”

He dropped her off, and continues to be in touch with the ‘Sunday Strangers’ page. She says, “He comments on all my (Sunday Stranger) posts.” Her project is also a meditation on how much our daily lives depend upon strangers in the sphere of work, commuting, leisure, and just existing in the urban space.

Open happiness

Long before she began the ‘Sunday Strangers’ project, Chendwankar had made a career out of openness to strangers. In 2010, she worked as researcher for a reality show which featured an actress who would solve domestic quarrels on television.

Researching for one such episode led her to a slum in Ghatkopar. Here, she met a family whose daughter was having problems with her mother-in-law. Chendwankar convinced them to share their problems on TV. She recalls, “They blessed me and invited me for lunch,” which touched her deeply.

Chendwankar has worked on research, been a costumes manager, and today she is a senior producer in the creative team, which means she makes episode structures. The field of reality TV, especially singing and dancing shows, has been booming for years now. But isn’t reality TV a fabrication at best? She answers, “We label it as entertainment.”

She adds, “Whatever people think about TV, I take it personally. I am making people happy. (The viewer) has come back from work, through traffic, and he has turned on his TV. I am making him happy.” Chendwankar knows she’s in the right field, she says, because of the satisfied look on her mother’s face when she watches Marathi serials on TV.

As a producer for a recently-concluded dance reality show, Chendwankar’s job involved scouting for strangers with a talent. Her ‘Sunday Strangers’ project, she says, is about strangers who are friendly. “It’s not my mission,” she says. “It makes me happy and it makes the other person happy.” As to the future of the project, she says, “It’s not a planned thing like a book or something. I (will keep at it) till I can.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!