Art historian Susan Hapgood’s new book provides keen insights into the port city’s fantastic experiments and relationship with photography in the 19th century, writes Kareena Gianani

Class with teacher in vernacular school, Bombay, by Shivshanker Narayan (1873). British Library, London/u00c3u0082u00c2u00a9 British Library Board

Bound and pressed between the pages of the book, Early Bombay Photography, are more than sepia-tinted photographs documenting an illustrious port city in the 19th century. No doubt, there are delightful topographical views, elegant studio portraiture, and subjects looking into the camera, some sitting ramrod straight, their gaze unflinching. What the book is, in essence, is a journey of revelation — into a city that not many know took to photography within a year after the daguerreotype process was introduced to the world (1839), and that, by 1850, it is likely that more people practiced photography in Bombay, than anywhere else in Asia. Early Bombay Photography is equally about the highly-charged social, political and aesthetic photographs which were produced by both British and Indians alike.

Class with teacher in vernacular school, Bombay, by Shivshanker Narayan (1873). British Library, London/© British Library Board

ADVERTISEMENT

It was discoveries like these which fuelled art historian and author Susan Hapgood’s research into the subject. Hapgood says she was gripped by 19th century Indian photography well before she moved to Mumbai from New York in 2010 and founded the Mumbai Art Room. The executive director of the International Studio and Curatorial Program in New York was delighted to find just how early on Bombay became a part of the global photography movement in the 19th century. “The field of study of non-Western photography is still relatively young. However, one will not find the same volume of photographs made in China, for instance, in the 1850s.

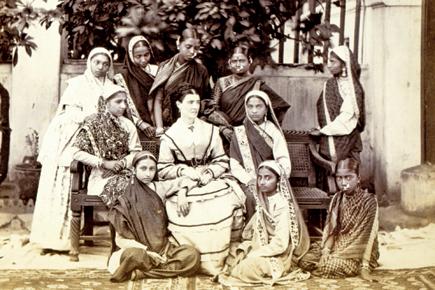

Vallabhacharya Maharajas, from The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay: A Series of Photographs, with Letter-Press Descriptions, by Narayan Daji and William Johnson. Vol I, 1860 or earlier, published in 1863. Courtesy of Farooq Issa, Phillips Antiques, Mumbai. In the book, Susan Hapgood notes how this photograph was the subject of a notorious libel case because the accompanying text discusses the “gross immorality” of the priests. “Back in the 19th century, the photograph was seen as the ‘truth’ and in the ethnographic studies, these images were accompanied by supposedly objective texts that read today as terribly biased descriptions. It sounds hilarious today, because we know better; but it is also tragic,” says Hapgood.

Bombay was quite the pioneer. I was stunned to discover that the first Indian Photographic Society was formed in October 1854 — merely a year after London got its first photographic society,” Hapgood tells us over the telephone from New York. The book also brings to the fore the stories of some of the earliest, enterprising photographers of Bombay, and how their works were politically and ethnographically significant. Hapgood says other histories have focused on British photographers in Bombay, but she was keen on fleshing out stories of India practitioners at that time.

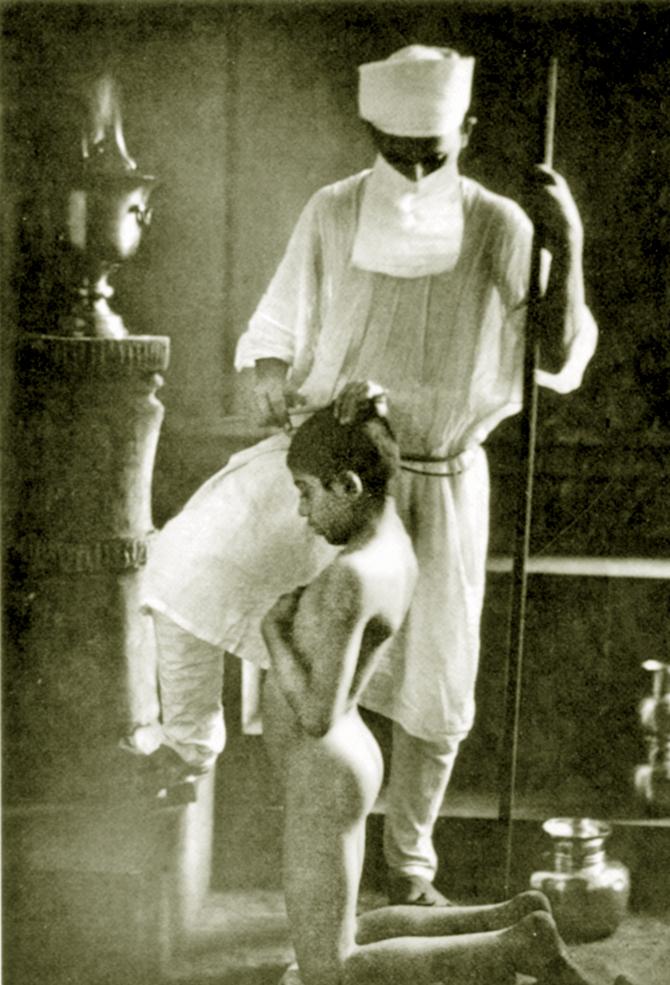

The Naver Ceremony — The First Ablution, in The Photogram, by Shapoor N Bhedwar (1894). Courtesy of PhotoSeed Archive. Susan Hapgood was drawn to the aesthetic sensibility of Bhedwar, who was “deeply embedded in the international photography circuit and whose pictures were in tune with the global art movement”.

She was particularly piqued by Hurrichand Chintamon. “He is considered to be the first Indian to run a successful photography studio (in the late 1850s). Even today, if you go to any antique store in Mumbai, pick up an old portrait and turn it over, chances are that you will find Chintamon’s name printed on the back.

The Flower Girl, from The Feast of Rose series, by Shapoor N Bhedwar (1890). National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

He was a fascinating character; 23 of his group portraits were exhibited in Paris in 1867 and he travelled to England in 1871 where he was soon inducted into the Royal Society of Arts,” says Hapgood. The book also features the photographs of Shapoor Bhedwar, who was deeply embedded in the international photography circuit and whose pictures were in tune with the global art movement.

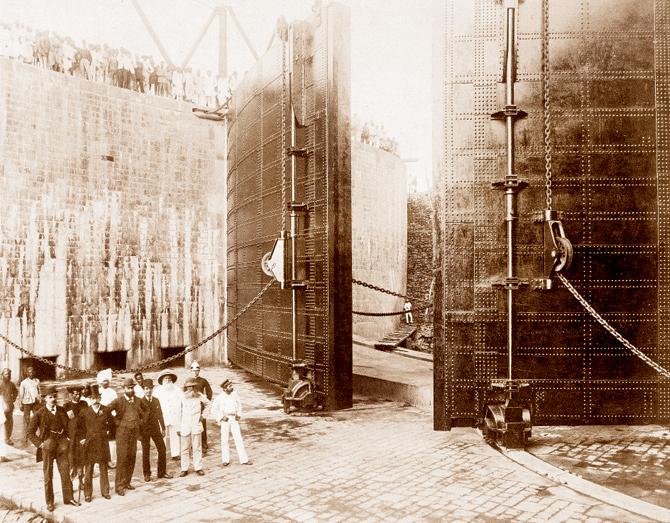

80-Feet Entrance. View Of Back Of Gates And North Culvert Openings — Group of Engineers and Contractors (Victoria Dock Construction, Bombay), by Edward Taurines (February 21, 1888). British Library, London/© British Library Board. Susan Hapgood points out the way Taurines’ photographic eye commands attention to this engineering marvel and shows the man in white, dwarfed by the mighty gate, standing near the large pile of planks.

Hapgood says her “jaw dropped” when she discovered how legendary American photographer, Alfred Stieglitz, praised Bhedwar’s work as “having a richness of tone and delicacy rarely seen at a photographic exhibition”. Over the course of her research, Hapgood had many moments wherein she was struck by awe. “I was at the Maharashtra State Archives in 2010, poring over original handwritten documents about the first photography classes in Bombay, how many students had registered, and so on. And then, in 2011, at the British Library in London, I stumbled upon the exact same documents, in longhand copy, because duplicates were made of anything deemed important for record-keeping."

Trench of East Wall Cut Through Rock, Looking South (Victoria Dock Construction, Bombay), by Edward Taurines (December 19, 1885). British Library, London/© British Library Board. Susan Hapgood says she finds this photograph aesthetically appealing, especially the way light is used to look like water bouncing. “Yet, you can’t miss how upsetting this show of the British marshalling labour is,” she adds.

However, awe was not the only emotion that ran through Hapgood’s discoveries; she also had unpleasant run-ins with the colonial mindset. She says she was jolted by the racial tones of the texts that accompanied many government-commissioned portraits taken during that time. In the book, Hapgood draws attention to the memorandum Lord Canning, the Viceroy of India in 1861, sent instructing all provincial Indian governments to gather photographs as “characteristic specimens” of the “more remarkable tribes”. “It was like they weren’t even talking about human beings,” she says.

Untitled View of Bombay (1869). Photographer unknown. From the collection of Gopal Nair, Mumbai

Untitled View of Bombay (1869). Photographer unknown. From the collection of Gopal Nair, Mumbai

Early Bombay Photography is undeniably a significant addition to history of 19th century photography in Bombay. Hapgood, however, says there are two more places in Mumbai in which further research will throw up more surprises: “Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum has a fabulous collection of glass plate negatives from the 19th century.

Susan Hapgood, Trustee, Mumbai Art Room

And the Piramal Art Gallery has a treasure trove of photographs collected by author and academician Judith Mara Gutman, waiting to be examined.” Early Bombay Photography, by Susan Hapgood, published by Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad (www.mapinpub.com) in association with Contemporary Arts Trust, Mumbai. Price: Rs 1,950

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!