A new interactive drawing in London by Mumbai-based artist Ranjit Kandalgaonkar takes us back to the years in which this city suffered a plague outbreak and the urban legends that surrounded it

The wily oriental rat flea, the vector for the bubonic plague, hardly took the blame for the outbreak of the deadly disease in Bombay in 1896. The epidemic that hit the city saw a number of reactions, some of which border on the ridiculous, from Indian residents and British officials. The public response to the epidemic has now resurfaced in a drawing by Ranjit Kandalgaonkar as part of an ongoing exhibition called Ayurvedic Man: Encounters with Indian Medicine at Wellcome Collection, London.

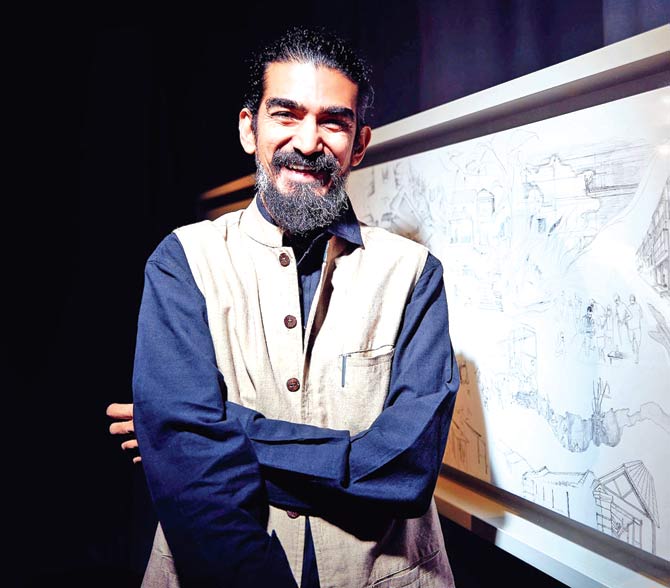

Ranjit Kandalgaonkar with his drawing at Wellcome Collection, London

ADVERTISEMENT

The Mumbai-based visual artist and researcher was commissioned this year by Wellcome Collection, a museum and library in London that explores the connection between science and art. The commission, titled Drawing the Bombay Plague, is on a 10-ft-long canvas and narrates the panic-struck, misinformed reactions from the public. The commission follows Kandalgaonkar's three-month residency, supported by the Charles Wallace India Trust and Inlaks Shivdasani Foundation, at Gasworks, a non-profit visual art organisation in South London.

The members of the Bombay Plague Committee. Seated in the centre is William Forbes Gatacre, chairman of the committee. Pics/WellcomeâÂu00c2u0080Âu00c2u0088Collection

“Drawing the Bombay Plague is an exercise in highlighting how public misconceptions about disease persist through fear, fantasy, paranoia and rumour. Interspersed alongside the drawing are misplaced statistical data on plague measures, produced by the authorities to shock subjects into submission, albeit with varying results,” says Kandalgaonkar. The drawing is the result of research primarily through the photographic archives at Wellcome Collection, a three-volume report by William Forbes Gatacre (the Chairman of the Bombay Plague Committee in the late 19th century) and Pickings from the Hindi Punch at the Asiatic Library in Mumbai. There is also recent research by experts, such as historian Prashant Kidambi, that Kandalgaonkar refers to. “The Gatacre report has an 'index of evidence' which documents all the work that was carried out by the British administration to tackle the outbreak. That index can seem self-incriminating,” says Kandalgaonkar.

Racist science

The index cites instances such as locals getting upset by disinfectant baths and sprays that they and their houses were forcibly subjected to. “There is also an entry that considers whether plague is spread by ants, which is dismissed for lack of evidence,” says the artist.Kandalgaonkar says that the British officials held many casual racist assumptions that hampered their scientific method. For instance, there were doubts about whether it was the Gujarati traveller, who often went to meet his relatives, who was the vector for the disease.

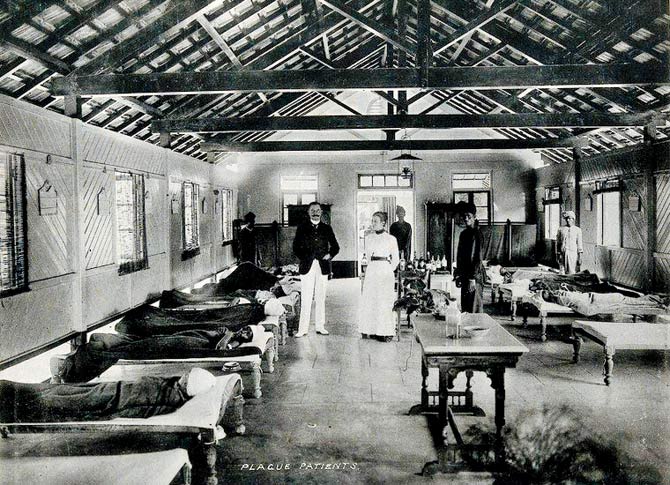

Doctors attend to plague patients in a city hospital between 1896 and 1897

Referring to Kidambi's research, Kandalgaonkar says that British officers were inclined to ascribe the origin and the spread of the disease to filth and sanitary disorder, rather than just the flea. Naturally, the poorer Indians, who lived in relative squalor by the docks, where the plague first broke out, were the worst targeted. There was even some reasoning that the British, who wore boots and slept on beds, were safe. In another case, sunlight entering dirt-ridden areas was seen as a cure for the plague. “The reason for the outbreak, as was later discovered, was, ironically, the mercantile routes of the British, from Hong Kong to Bombay. As more and more ports put ships from Bombay on quarantine, the British administration panicked,” says Kandalgaonkar.

Punch sheds light

Kandalgaonkar's research at the Asiatic Library in the city was through the old pages of Hindi Punch, a local version of the British weekly humour and satire magazine. Pickings from these issues served as a record of the plague years, with cartoons that commented on the situation. “In one of the cartoons from this time, a family considers leaving the city in a hot-air balloon, so that the odorous, microbe-ridden air wouldn't reach them,” he says.

A plague goddess?

These instances find place in his drawing, which has been made into an interactive surface through Wellcome Collection's team. The drawing narrates incidents sourced from these records, such as the family's wish to fly away from the city as well as the forced spraying of disinfectants on houses. There are also two goddesses on either end of the drawing - one is Ola Bibi, a Bengali demigoddess associated with curing cholera; the other is Sitala Devi, the broom-wielding goddess who was prayed to for recovery from small pox, and now, for chicken pox.

Kandalgaonkar brings up Colonizing the Body by David Arnold, where the writer states, “Plague, like smallpox and cholera... emphasized the enormous differences in perception and response - indigenous and colonial alike - between one epidemic disease and another. One illustration of these differences was the virtual absence of a plague deity, comparable to Sitala for smallpox or cholera's Ola Bibi... It was the state's motives which provoked a crisis of comprehension, not the activities of an irate or capricious goddess.”

In the mayhem that ensued the epidemic, the flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, was considered as just one of the many suspected vectors of the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis, and got away with the death of about 22,000 people between 1896 and 1900.

Also see: These Mumbai tantriks raped women on the pretext of 'healing' them

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!