The Boatman, a book by former aid worker John Burbidge, is set in India during the early 1980s, unearthing facets and talking about Mumbai landmarks which were part of a thriving but subterranean gay scene

Foraging around the internet for the phrase ‘Bombay Bandstand’ yields an odd million or two hits for the star-strewn promenade at Bandra, a heady sea-sprayed stretch of concrete that has been in existence for less than a decade.

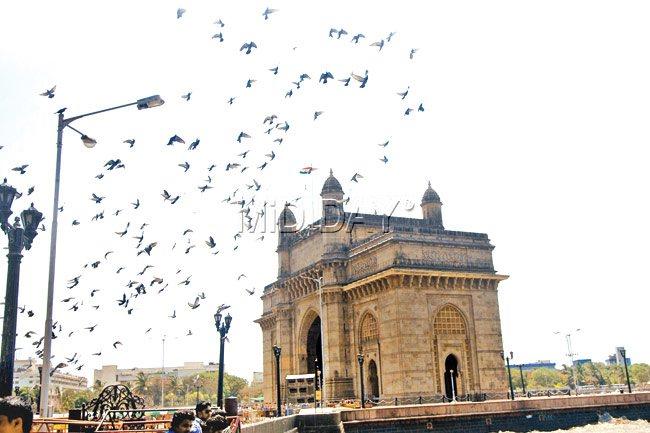

TO BE FREE: Like these pigeons at the Gateway, silent sentinel to the subterranean gay culture in the city in the '80s and '90s. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

ADVERTISEMENT

Bandstand culture in Mumbai, now seemingly obscured on the internet, actually goes back a whole century or more. References to it can be found in vintage texts and jazz tomes, although there has been a resurgence of interest in recent times (if ever so slightly), via the good offices of the Bandstand Revival project, which has attempted to bring back elusive traces of a bygone era by springing the pomp of an after-dusk live brass band upon an unsuspecting populace, who have long become completely inured to such instances of embedded culture. However, unknown to many except those with first-hand experience (many of whom were sworn to secrecy by the dictates of those times), the twilight whirring at a bandstand has also been associated with the carousel waltz of an underground culture from as far back as the 70s, with the Cooperage Band Stand Garden and Children’s Traffic Park in Colaba (or simply, Bandstand) once being the crowning glory of a thriving gay scene in the city, and a symbol of her subterranean hedonism.

Parallel

Ever since India Today placed its partial archives in the public domain, the rare early article on homosexuals has allowed us a tantalizing glimpse of this parallel culture. A 1984 piece talks of a gay gathering at the Bandstand on New Year’s Eve, with “exclusively male revellers who circle around the pony track, exchanging greetings with old friends, while some huddle in pairs in the darkness." The article features a photograph of a gay couple getting cosy in a Mumbai (called Bombay then) park, their faces obscured even if their demeanour spoke of a new openness that, in many ways, we are still talking about in those terms, even now. This was before Ashok Row Kavi's mother talked about her gay son so forthrightly in a 1986 issue of Savvy magazine, which for many observers of the gay movement (especially those who link its advent with AIDS outreach programs), was the moment history began.

Book

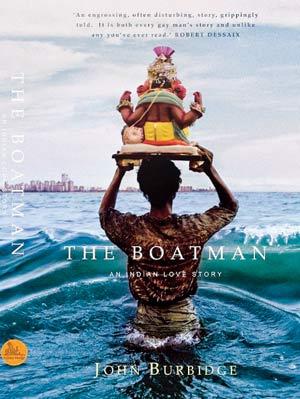

Now, a new book released earlier this year by Yoda Press, adds an intriguing prologue to this narrative. The Boatman, by former aid worker John Burbidge, is set in India during the early 1980s, and unearths many facets of a scene in its salad years, untouched by the activism, identity politics or notions of visibility that came much later, and caught in the quagmire of deep-seated repression, with its secrets, lies and unrelenting truths, and equally, untold treasures.

DECODED: The book is essentially one of celebration

Bandstand, as the Australian Burbidge describes it, was a “blazing beacon in an ocean of darkness”, and held an iconic status for gay men throughout India. The book details episodes of midnight hour revelry, amorous encounters with a long line of both cultured and proletarian men, as well as run-ins with the law. Even then, policemen had already discovered the fairly lucrative sideline of pocketing bribes from hapless gay men who were in no position to be outed, and paid up readily. It is a practice that continues to this day, with the plain clothes officer a constant feature at even the shadiest of cruising locations. However, the general tenor of the book is one of celebration, and of discovery. Burbidge came from a deeply conservative background, and it was in India, as a 30-year-old, that he was able to finally experience men, flesh and soul.

Liberation

Thus, over the years, the Colaba Causeway unwittingly became the first bastion of gay liberation in the city, given how it strung together so many sites of historical significance to queers.

Filmi flavour: Internet searches throw up Bandra Bandstand, when one searches for Bandstand. Pic/Atul Kamble

Starting with the old stamping ground at Cooperage, so beloved of Burbidge, where lustful sailors from the Naval institute once looked in for fresh pickings, to the Gateway of India where clandestine pick-ups still take place with utmost alacrity, then moving right along the windswept Wellington Pier, with drinking joints Voodoos and Gokul all within shouting distance, one could possibly trace the path of a vintage-era pub crawl. In the 90s, Gokul's upper level “had been colonised by (gay men), from (where) they could plot the seduction of the sturdy labourers drinking downstairs”, wrote openly gay author Manil Suri in the literary journal, Granta. The place is now just a run-of-the-mill pub (with the most affordable alcohol, though) with its attractive bouncers only providing some benign gay interest.

Physiques

The Causeway itself provides an endless supply of international eye candy, with tight physiques nicely turned out in the invitingly dressed-down casualness of backpacker attire. Peeking (as opposed to leching) is now a national pastime, and perhaps doesn't even bear an overt sexual charge anymore.

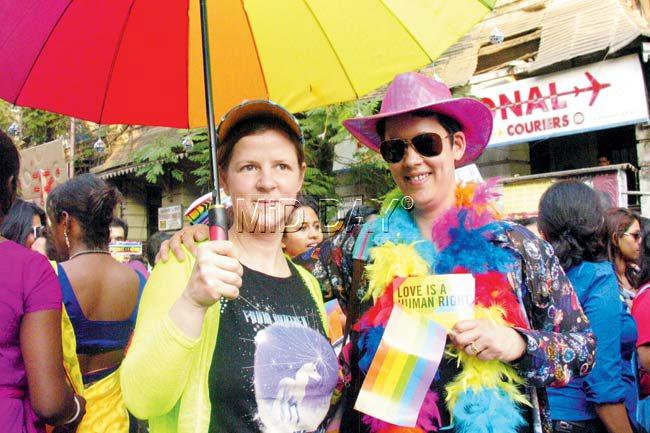

VISIBILITY: Now the gay scene in the city has so much more visibility. An LGBT rally. Pic/Suresh KK

Later, after collecting a large tumbler of Ice Green Tea Latte (extra macha, extra ice) at the spanking new Starbucks, one could take a detour into the promenade in front of the Taj and mingle with Arab men with long flowing robes. A few doors away from the Radio Club, if one is lucky, Voodoos would be open for the night, although the shutters are often down these days, and the moral police keeps getting blamed. Much much further up ahead is one of the gay universe’s best kept secrets — the Mumbai Port Trust Garden which, on most evenings, attracts quite a queer bunch. Some of Colaba’s multicolour environs have been enshrined for posterity in queer popular culture. In the film, Bombay Boys, Roshan Seth plays an old queen who picks up a young man at the Gateway, from a choice assemblage of several ‘types’. In a particularly affecting segment in Riyad Vinci Wadia’s seminal Bomgay, an expatriate eager to hear from his friends in India, receives a parcel finally, in which are photographs of shirtless men dancing the night away at Voodoo’s, of friends posing at the gents' toilet at Dadar station, and of the phallic Apsara Theatre steeple, so iconic for those early revellers (it has since been taken down).

Surreptitious

Memories of such tenuous modes of communication, now survive only in the oral accounts that are a testament to the thwarted lives and lost loves of entire generations. Like Burbidge, another person who lived out his romantic prime surreptitiously in the shadows of Colaba’s alleyways, was Farrokh Bharucha (name changed). Now in his fifties, the Parsi gentleman talks wistfully of his stash of old postcards, from long before cell-phones rendered obsolete the beguiling uncertainty of lovesick memos. One of the postcards is discreetly signed with just the initials of a paramour, DK, bearing a stamp smeared with the postmark, ‘On Her Majesty’s Service’. He keeps it interred in his old rosewood almirah, in a glory box of jewels and baubles and knick-knacks of little sentimental value to any one else. “He was my boyfriend, the only boyfriend I knew. It wasn't conventional. It wasn't about living together. It was about being in each other's hearts,” says Bharucha of a man he used to know from just the smell of his hand, or the lilt of his voice, or the glide of his hair, perhaps. On the postcard, DK had written he would visit Bombay, and for three hours every afternoon, he would wait at the Gateway for him. Bharucha never went. Sometimes the leap of faith required was too much. “Heaven knows what the cards would have foretold if I had allowed myself to take that chance,” he says. The chance of just one meeting that held so much life-changing force.

Signposts

These days, memories of casual encounters can be cast aside like crumbs on a lace doily, but Bharucha held on to his little signposts, to almost commemorate a life that never was. The story wasn’t something that was unique to him, it was shared with all those born into a society that did not need them, unless they played along and pretended to not be different. Happiness depends upon those snatched opportunities on which the accidents of life can arrange themselves miraculously. Opening oneself to that infinite unknown could be the difference between a life well spent and one lost in the darkness of eternal denial. Burbidge’s catharsis was effected by India's welcoming underbelly, the nether reaches of which has snuffed out too many lives. Long after men and women pass into oblivion, the ethereal markers of those lives can be found on benches and pavements, in a favourite stool at a café, in a secluded spot at a park. Colaba has borne witness to personal histories that have never been committed to paper or tape, but their traces, nonetheless, will always remain.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!