Mid-Day Anniversary Special: Top cop Rakesh Maria learns methodologies change, motivations remain constant when it comes to crime

Top cop Rakesh Maria learns methodologies change, motivations remain constant when it comes to crime

25 July, 2025 06:56 PM IST | Vinod Kumar Menon

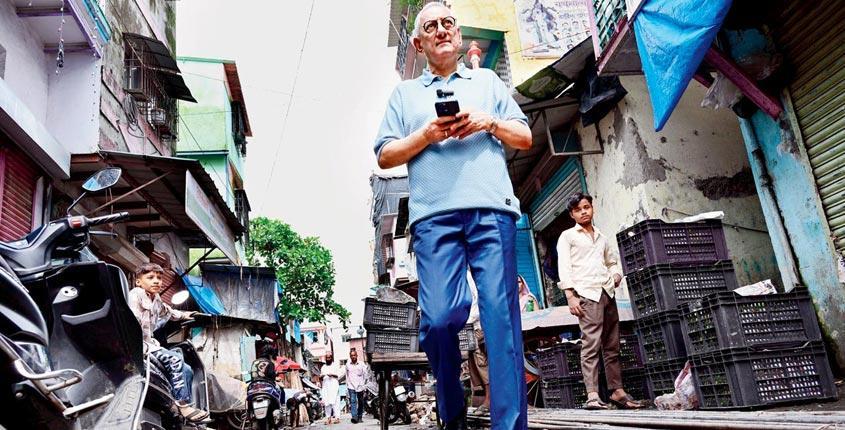

Super cop Maria at the site of a grisly murder at Padma Nagar, Deonar. Pics/Rane Ashish

Rakesh Maria, Director General of Police

From the Files of Rakesh Maria — 1981 batch IPS Officer, Retired on January 31, 2017, as Director General of Police, Commandant General of Home Guards, and Director of Civil Defence, Maharashtra.

On February 3, 1987, Rakesh Maria became the DCP of Zone IV Matunga, succeeding Y C Pawar. Before this, Maria served as Superintendent of Police in Osmanabad, a district in southern Maharashtra’s Marathwada region, which was renamed Dharashiv in 2023.

Maria said, “When I took charge as the Deputy Commissioner of Police, Zone IV in February 1987, the city was different — raw, chaotic, and unforgiving. My jurisdiction stretched from the Passport Office near Century Bazaar all the way to the Mahim Creek, ending just before the Vashi Toll Naka. Nine police stations fell under my supervision. These were Dadar, Mahim, Matunga, Dharavi, Antop Hill, Chembur, Trombay, RCF and Deonar. Unlike today, where these areas are divided amongst three separate DCPs, back then, they all came under one zone i.e. mine (Zone IV)” recalled Maria.

Maria recalled, “Padma Nagar Zopadpatti was once a tangle of narrow lanes and tin roofed shanties, then falling under the jurisdiction of the Deonar Police Station. Today, it has transformed into Padma Nagar, a gentrified neighbourhood dotted with two-storey concrete homes. What was once a single police station jurisdiction is now divided among four police stations, Deonar, Govandi, Mankhurd, and Shivaji Nagar.”

Rewind to late summer of May 1987. “It (Padma Nagar Zopadpatti) was the scene of the most gruesome murder case I had seen till then and one that would teach me lessons I would carry for the rest of my career,” Maria recalled, as he stood in front of Padma Nagar, thirty-eight years later...

Maria did a deep dive into the case. “It was a routine visit to Deonar Police Station, sometime in the last week of May, 1987. I was reviewing police station records when Constable Gangurde and Detection officer (Goonda Squad) Chaskar came to me, faces tense, eyes serious.”

“Sir, there’s something you need to know,” Chaskar said. “A murder... in Padma Nagar.” I looked up sharply. “Murder?” Maria recalled.

An informant had tipped them off. Maria reminisced, “A man named Alam Qureshi, 45, a fitter at the docks, had gone missing. He lived with his much younger wife, Parveen Sultana (18) in the Padma Nagar Zopadpatti. To make ends meet, they had rented part of their two-room hut to an auto-rickshaw driver named Sharfuddin Samsuddin Khan. Alam worked long hours in shifts at the docks. In his absence, Parveen and Sharfuddin grew close — what began as a quiet liking soon turned into a full-fledged affair. The neighbours whispered, and eventually, Alam began to suspect something was wrong. Fights broke out, he abused her verbally and physically. The situation worsened, until it reached a boiling point.”

Maria went on, “Fed up with the abuse from her husband Alam, Parveen, with her paramour, Sharfuddin, hatched a brutal plan to eliminate Alam. One evening, Alam returned home from the docks. Parveen cooked a meal, as usual. What he didn’t know was that she had laced it with a sedative. As he slipped into sleep, Parveen signaled for Sharfuddin. The man arrived and brought someone with him, Shahnawaz Mohinuddin Khan, just 19, a rag picker, who spent most of the time at the Deonar Dumping Ground, located 2 to 3 kilometers from Padma Nagar Zopadpatti. They offered him Rs. 40 — enough for a plastic / polythene sheet and bamboo poles to cover his hut before the monsoon hit. That was all it took.”

Maria went on, “Together, they smothered Alam with a pillow. Then came the horror. They dismembered the body, packed the parts into plastic bags, and loaded them into Sharfuddin’s auto. Under the cover of night, they dumped the mortal remains of Alam at Deonar dumping ground.”

From death to deception. From Maria’s files we learnt, the very next day, Parveen walked into Deonar Police Station — crying, frantic. She wanted to file a missing person complaint. Her story was well-rehearsed. She said Alam had run away with another woman. That he was abusive and assaulted her, every time she questioned him of his affair. And he had left in a fit of rage and never returned.

But something didn’t add up. The Goonda Squad of Deonar police station started digging. Human intelligence sources whispered the truth.

Alam wasn’t missing. He was dead. Murdered.

Maria ordered a swift response. “Pick up the rag picker first,” he told Gangurde and Chaskar, instructing them to take the police team along. “We found Shahnawaz and brought him in. Under pressure, and with the guilt of a teenager who had sold his soul for shelter, he finally broke,” recalled Maria.

“He confessed. Pointed us to the spot. It took over 14 hours of digging through filth and garbage to recover what was left — a severed hand, part of a thigh. The body was never found in full.”

By then, Maria’s file said, Sharfuddin was already in custody. He too confessed. Parveen was picked up last. Her mask of sorrow was gone. Now she sat cold, calculating. But the story was out.

Maria analyzed, “We had no CCTV. No mobile phones. No DNA analysis. But we had instinct. Human intelligence, that led us to uncover a brutal murder.

We turned Shahnawaz into an approver (pardoned), and based on his testimony, both Parveen and Sharfuddin were convicted by the court.”

Most of all Maria said, “I walked away from that case with two lasting lessons.”

First: In Mumbai, the value of a human life was just Rs. 40.

Second: You don’t need a professional killer. Just desperation.

These lessons that have stayed with him through the years, and a message Maria wants to pass on to young officers is,

“Today we have advanced tools, scientific aids, mobile evidence, surveillance and CCTV cameras. But there’s no substitute for human intelligence. Criminals may change their methods, but the motivations which are jealousy, greed, lust and fear remain the same. Never trust a complainant at face value. In every case, everyone is a suspect.

Detection isn’t just a skill — it’s a mindset that begins from within. To solve the toughest cases, you must listen carefully, observe closely, question relentlessly, and suspect everyone: even those who come to register complaints at the police station. No one should be exempt from suspicion. With thorough investigation and modern scientific tools available today, convictions in court are bound to follow,” said Maria.

Maria brought the conversation back to his first case. He said, “This case wasn’t just about a murder. It was about understanding the city — its desperation, its decay, and its drama. A man’s life ended over just Rs 40. You don’t need a professional killer for that — only desperation. From that darkness came a lesson that has stayed with me for a lifetime,” Maria concluded.

1987

Year he became DCP Zone IV

Tejas Mangeshkar

Tejas Mangeshkar and Mukul Deora of Bhavishyavani Future Soundz were all about living for today, planning for tomorrow and partying tonight

Dhruv Ghanekar

Dhruv Ghanekar, co-founder, blueFrog broke rules to hit the high notes

Anees Bazmee

Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3 director Anees Bazmee on working with the showman of Indian cinema, Raj Kapoor. He started working there at the age of 16 and would take four buses to reach the studios in Chembur

Abhishek Bachchan

Abhishek Bachchan rewinds to the star-studded première of his debut film at Liberty cinema

Viren Rasquinha

Former India hockey captain Viren Rasquinha talks about finding his playing feet on his first surface