... tiles would be its landmarks. As an exhibition in the city ponders the memories of Mumbai-s floors, we find an excuse to focus on the different histories presented by colonial and economic interests

Ahura Building on Mancherji Joshi Road, Dadar Parsi Colony, was built in the 1920s. The second floor home of Mahrokh Joshi has two tile patterns. While the hall sports cement tiles of the Minton pattern, the balcony and an inner bedroom have cement tiles

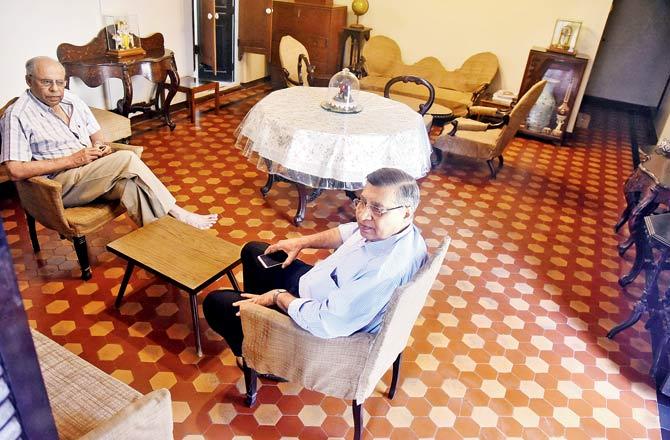

Sitting in the living room of her Peddar Road home Marlboro House, Pushpa Palat says the only time they gave the tiles of their apartment, one of seven in the 1938-built building, a deep clean was when they purchased it in 1998. Since then, they have only washed them with water. No floor cleaners. "If there-s a stain, you scrub it and over time, it will go. But, I had been warned early on not to apply any chemicals to the flooring," says Palat, author and journalist. You-d think that the tiles then would reflect the wear and tear. The house after all, as Palat insists, is child- and dog-friendly. Yet, the only thing that the tiles reflect is the abundant sunlight from the large windows.

That Palat and her husband Raghu, a banker, are proud of the heritage of the house would be an understatement. They reel off its history as they take us on a tour. Built by British architect Claude Batley—whose other works in the city include Bombay Gymkhana, Lincoln House and Bombay Central Station—they say the house has been built in Art Deco style and was initially made for a German lady who didn-t end up staying because she had to leave the country during World War II. "Interestingly, each room has the tiles laid out differently. In fact, each apartment in the building sports different styles," says Palat. Unfortunately, we can-t see that for ourselves because all other residents have replaced them with modern ones.

Marlboro House at Peddar Road is home to Raghu and Pushpa Palat. Atul Kumar, Founder, Art Deco Mumbai Trust, says that in terms of design, what set Art Deco tiles apart was the unique geometry, directionality and nautical elements incorporated. "For instance, if you look at the flooring in marble at the Churchgate-s Empress Court lobby, it is abstract. Within it, there is a big black arrow pointing into the gate of the lift," says Kumar, adding that even inside apartments, one often finds design indicators leading to different rooms. "The colours were vibrant because Art Deco was a reflection of early modernism. It was flamboyant, some even call it loud. There were blacks, greys, maroon, red, yellow. The first floor of Court View building opposite Oval Maidan, for instance, is a riot of colours," he adds.. Pics/Pradeep Dhivar

The Palats aren-t Mumbai-s only residents who have a thingfortiles. At Colaba art gallery Tarq, an exhibition by artist Vishwa Shroff, uses tiles found in Mumbai-s buildings as a tool to speculate on how time and architecture collide. For the exhibition, called Folly Measures, text written by Veeranganakumari Solanki states: "Recontextualization and reconstruction of time and change are meticulously recorded in the details of mismatched tiles, landings, residues and lines...Floors become pattern libraries of interruption, while worn tiles become a chronicle of chanced memories. Architectural features become the carriers of change and time frames. Material compositions from changing fads of marble, concrete, kota stone to mosaic tiles, banisters and old walls, each tells a story from a chapter in time."

Shroff, 39, says that tiles take on time well. "They have scratches and other time markers and are vulnerable. That-s what interests me." For this part of her exhibition, she made multiple visits to buildings between Navy Nagar, where she lives, and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, observing the tiles on the staircase landings. She has also recorded where her view has been blocked due to the placement of furniture. Which buildings these are, Shroff will not say. Hena Kapadia, Tarq-s gallery director says they have had residents of the buildings come to the exhibition and not realise what lies beneath their feet.

Tehmi Terrace was built in 1914. Historian Heta Pandit, whose family owns the Turner Road structure, says it was renamed after her grandmother Tehmina Rustamjee Patel, when the family moved here in 1942. The Grade III heritage structure, says Pandit, has been built in vernacular style - while the essential style is inspired by British architecture, it was built by a Maharashtrian and sports certain Indian features. The floors have Minton tiles in the living room and local clay tiles in the passage areas. Pics/Ashish Raje

Vishwa Shroff at her exhibition, Folly Measures, at Tarq. Pic/Ashish Raje

Dhuru Lodge on Dadar-s Swatantra Veer Savarakar Road, has been around since the 1800s. "The house was built by our great grandfather Cassinath Dhuru-s father Deoji," says Ajit Dhuru, a retired media professional. In the 1930s, the property had a stable for horses as that was the popular mode of transport. Built in typical British villa style, the house was, in the mid-1990s, included in the heritage list as a Grade D structure. However, in a later revision of the list it was taken off. The tiles, says Variava, are clay tiles, possibly imported from England. Pics/Pradeep Dhivar

World history impacted Mumbai tile choice

Firdaus Variava, of Bharat Floorings and Tiles, explains that the earliest tiles in Mumbai were those made of natural stone. In the 1930s we got terrazzo—a composite material, poured in place or precast, which is used for floor and wall treatments; it consists of chips of marble, quartz, granite, glass, or other suitable material, poured with a cementitious binder for chemical binding, polymeric for physical binding, or a combination of both. It was in the 1970s that we got ceramic followed by marble and vitrified tiles.

Conservation architect Vikas Dilawari adds that when talking of the late 19th century, which is when CSMT or former VT station and other Victorian buildings came up, is when we started using Minton tiles or encaustic tiles—first developed by Cistercian monks in the 12th century England, encaustic tiles faced a crisis when Henry Tudor VII closed the monastries because the Church refused to grant him a divorce from Catherine of Aragon. The art form was revived in the 1800s by Henry Minton—which are fired tiles were used in Victorian buildings in the UK. For instance, the Rajabai tower arcade has an undisturbed pattern, making it look like a carpet. These tiles became very popular and became associated with Victorian buildings. What started with public buildings slowly became a craze with elite homes adopting the same style.

"There were highly decorative versions [of Minton tiles] and then there were the simplified versions which were less embellished. Two octagonal tiles of different colours, less ornate, were more prevalent in Mumbai homes. These were also Minton tiles." But, there were many areas which had no tiles, for instance, floors with Indian pattern stone flooring. These would have been carpeted. Before Minton, wooden flooring was common. The disadvantage was that these could not be washed. There would be cavities and below the floor would be another false ceiling of wood. This is what we see at Esplanande House , Dilawari adds. In Mumbai When the economic recession followed between the two world wars, i.e. 1919 and 1939, the need to make materials faster, economical and due to Gandhiji-s Swaraj movement pushed the need for alternative tiles i.e. cement tiles. Minton tile patterns came in cement versions, for instance, something we see in Bharat Tiles. Dilawari points to the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum and says that the special exhibition centre on the top floor of the Byculla structure sports cement tiles in Art Deco pattern—the ceiling of this floor was repaired in late 1920-s/early 30-s. Whereas the gallery has a carpet of Minton tiles. When new buildings began to be constructed in the 1930, -40s and -50s around Oval Maidan, says Dilawari, concrete tiles were used.

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!