A young Kathak exponent from Mumbai fights geo-political chaos, the pandemic and prejudice to find a guru across the border who is keeping the original Lucknow gharana tradition alive

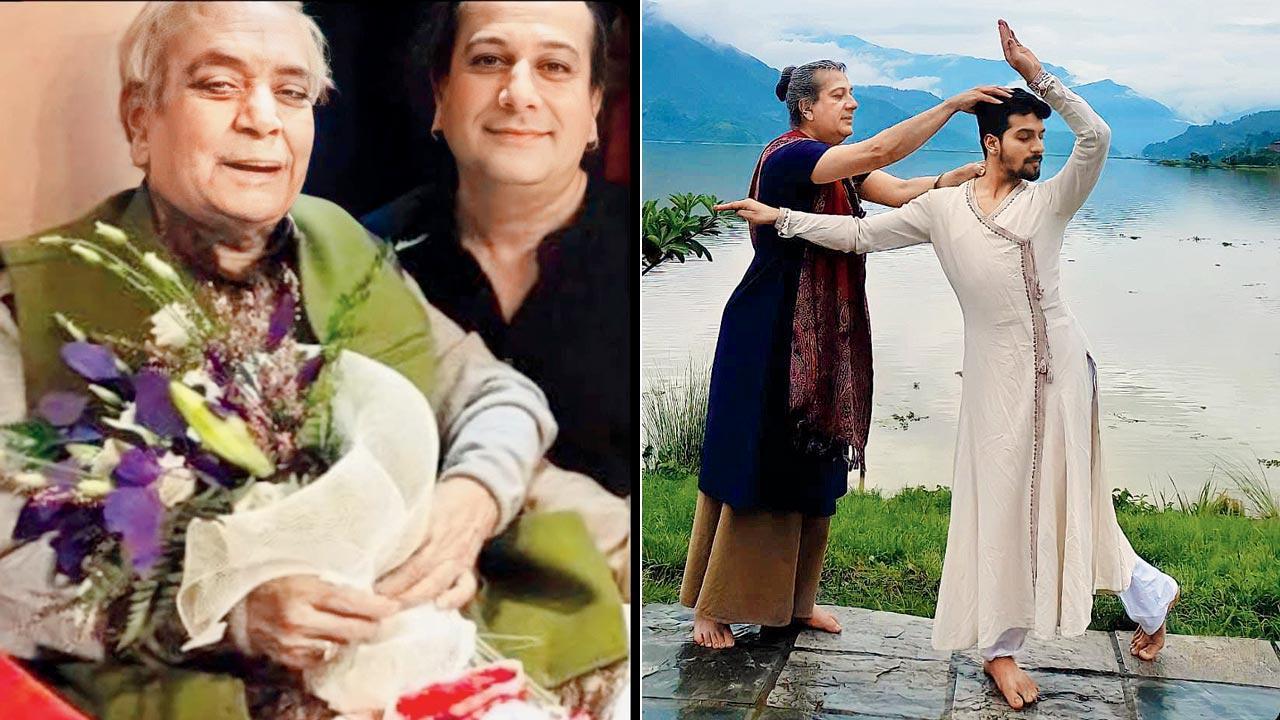

Fasih ur Rehman’s guru Maharaj Ghulam Hussain trained under Pt Acchan Maharaaj, Kathak legend Birju Maharaj’s father; (right) Sushant Gaurav, a Mumbai-based Kathak exponent has been taking online classes with his Pakistani guru Fasih ur Rehman for two years during the pandemic. This year, he was able to meet him in person and explore the world of Kathak beyond “bhakti andaz” involving mythological themes

It is well past midnight. Both, ustad and shagird have lost track of time as the ghungroos keep beat and the music gains momentum. The alliteration created by Kathmandu and Kathak is finding a literal playing out in the Nepalese capital with “the dancing Afghan”, Ustad Fasih ur Rehman, taking Mumbai’s Sushant Gaurav, through the paces.

The disciple follows the maestro’s moves in tandem, seamlessly executing shifts in rhythm in a stream of eloquence and grace under the teacher’s watchful eye. It has been two years of online dance sessions between the two until recently when they first met. “Though I had played the scenario in my head several times over, when I first met Ustad ji, I was tongue-tied. It was like the soul meeting the divine,” says Gaurav, a Mumbai-based Kathak exponent. “I now know why both, Fasih ji and the late Birju Maharaj ji say, ‘Ustad se mohabbat na hui, toh kya seekha?’”

But how did the two find each other? Gaurav discovered Rehman’s videos by accident on YouTube. “Enthralled with his form, perfection of movement, footwork and andaaz, I was smitten,” remembers Gaurav, who was then training in the Lucknow gharana style under Pt Birju Maharaj’s daughter and disciple Mamta Maharaj. He had been part of workshops with Pandit ji too.

Fasih ur Rehman loved dancing to Noor Jehan, Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhosale’s semi-classical songs that played on Radio Pakistan. Seeing this passion, his folks sent him at the age of 10 to train under Maharaj Ghulam Hussain (right), who taught Kathak

Fasih ur Rehman loved dancing to Noor Jehan, Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhosale’s semi-classical songs that played on Radio Pakistan. Seeing this passion, his folks sent him at the age of 10 to train under Maharaj Ghulam Hussain (right), who taught Kathak

Gaurav’s attempts to reach out to Rehman via Facebook messenger drew a blank for the first 10 attempts. “Before I come across as this evil ogre, let me clarify that I was only testing his motivation,” smiles the maestro, who finally agreed to get on a video call with Gaurav. “Sushant’s passion and humility to learn was evident. I told him to join a forthcoming workshop.”

Though the pandemic saw the workshop cancelled, Gaurav continued to pursue Rehman to understand the nuances of dance that he had in turn learnt from his guru Maharaj Ghulam Hussain, a disciple of Pt Jagannath Maharaj, known more popularly by the moniker Acchan Maharaj.

Gaurav wanted to explore the world of Kathak beyond “bhakti andaz” involving mythological themes. “While a lot of Kathak in India centers around the Bhakti movement, there is relatively little to show for the stylised Mughal era andaz that played a pivotal role in shaping the art form’s aesthetics,” says Gaurav, adding, “I also wanted to focus on the works of Mirza Ghalib, Amir Khusro, Siraj Aurangabadi, Bulle Shah and other Sufi composers whose works find lesser representation in contemporary Kathak grammar.”

Rehman insists that rhythm cannot be the be-all of Kathak and asks for dancers to cultivate movement in slow tempo

Rehman insists that rhythm cannot be the be-all of Kathak and asks for dancers to cultivate movement in slow tempo

Rehman echoes Gaurav’s lament on the loss of the dance’s meditative component. “This dance and its geometry of movement is part of the larger tapestry of architecture, language, lifestyle, textile and poetry of the subcontinent with each form borrowing influences from the other. This, combined with the foundations of the gayaki ang, gives Kathak composite beauty.”

Rehman should know. His repertoire is enriched with meditative Sufi flair and exemplifies frugal elegance and piercing subtleties in movement that typifies the north Indian classical dance form harking back to the subcontinent’s medieval past. None less than the late Pt Birju Maharaj had noticed this and in a video call, asked Rehman to teach Gaurav.

When the dark cloud of COVID rose, both ustad and shagird began to liaise over video calls. “Ustad helped me re-understand the basics,” remembers Gaurav, who found it refreshing that his teacher was also keen on exploring themes beyond mythology. Rehman underlines the importance of the contemporary in performing arts. “Both, performer and audience need to be able to connect with what is being presented with their own lived experience,” he tells mid-day.

They say that there are limitations to online training, although their sessions lasted six hours at a stretch. They are happy to return to intensive one-on-one training seeped in what they call thehrav.

Rehman frowns on the flashy routines that focus on fast rhythm. “Technical strength, with the body following the principle of sur along with the emotions one wants to communicate, forms the beauty of Kathak. Rhythm is necessary to keep the dance in a set time cycle and format but rhythm can’t be the be-all. The gurus of yore gave importance to slow tempo moves for a reason. I still practice those.”

The Pakistani maestro is all praise for Gaurav’s dedication and says the younger generation that he represents, holds promise. “If anything, we fall short in finding them good teachers and mentors,” Rehman says, “just like armed forces protect a nation, artistes protect a people’s culture, which is also its soft power. A geography will be barren without cultural exposure or diversity. Performing artistes are the cultural army with a huge responsibility in protecting and shaping up a country.”

Their tribe faces the challenge of dealing with a generation where actors Madhuri Dixit, Deepika Padukone and Alia Bhatt are considered gifted Kathak dancers by some. “Such an understanding has to do with exposure. Once they attend a live Kathak performance by an expert, they will understand the difference between Bollywood Kathak and the real thing. It’s not Madhuri, Deepika or Alia’s duty to create this awareness. This is the Kathak fraternity’s responsibility.”

Since they are at Durbar Square around the royal palaces of Nepal, one can’t resist asking them why they chose Kathmandu. Rehman points to Gaurav. “Where else? With winds of socio-cultural iconoclasm sweeping India and geopolitical ties between India and Pakistan on the chill, Ustad ji can’t visit India and I can’t go to Pakistan. This was convenient. We had earlier zeroed in on Sri Lanka but the island nation is grappling with a crisis.”

Rehman says he is sad India is going through the same iconoclasm that ravaged Pakistan. The great grandson of Princess Fatima Sultana of Kabul (who owned the Darya-e-Noor diamond given by her grandfather) loved to dance to Noor Jehan, Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhosale’s semi classical songs on Radio Pakistan. Seeing his passion, his family sent him to train under Maharaj Ghulam Hussain, who taught Kathak at a neighbour’s when only 10.

“By the time I began performing, General Zia-ul-Haq became the sixth president of Pakistan after declaring martial law in 1977, and ruled for 11 years,” Rehman recounts. “That regime was difficult for the arts scene. The government banned music and dance and wearing ghungroos was considered anti-Islamic. Being a lone male dancer in Pakistan was already difficult and with artistes targeted for pursuing what was seen as against religion, culture and country, became commonplace. That was the proverbial last straw.”

He remembers first shifting his classes from the first floor of the Lahore Arts Council to its basement to muffle the sound of ghungroos, and then stopping them altogether. Though many artistes fled Pakistan and settled abroad, he has continued to live in Lahore, and divides his time in London. “I had family here. Continuing college and making a living was tough. I only persevered because I was inspired by my Ustad, who established Kathak in Pakistan post-Partition from scratch despite the backlash from the government, religious scholars and people in general.”

Rehman says culture and the performing arts are beyond the shackles of religion, caste, language and nationality. He quotes his ustad: “Zarron ka raqs mastiye sehbaye ishq hai, alam rawan dawa, ba-taqaza-e-ishq hai [The dance of every particle in the universe is the expression of love, civilizations may come and civilizations may go and this truth of love is incomparable and immeasurable].”

This prods Gaurav to recollect the bigotry he faced when people heard that he had accepted Rehman’s tutelage. “Convert toh nahin ho rahe ho? Kya ab pranaam ki jagah salaam karoge?” he was asked. He says he concentrates on the love and support from family and others in the dance fraternity like Mamata Maharaj and veteran dancer-choreographer Jonathan Hollander. That’s sure to lead Lord Pashupatinath.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!