A new book, Bomoicar (Konkani for ‘Bombaywallah’), chronicles the life and times of Goans in Mumbai, through various voices. An extract

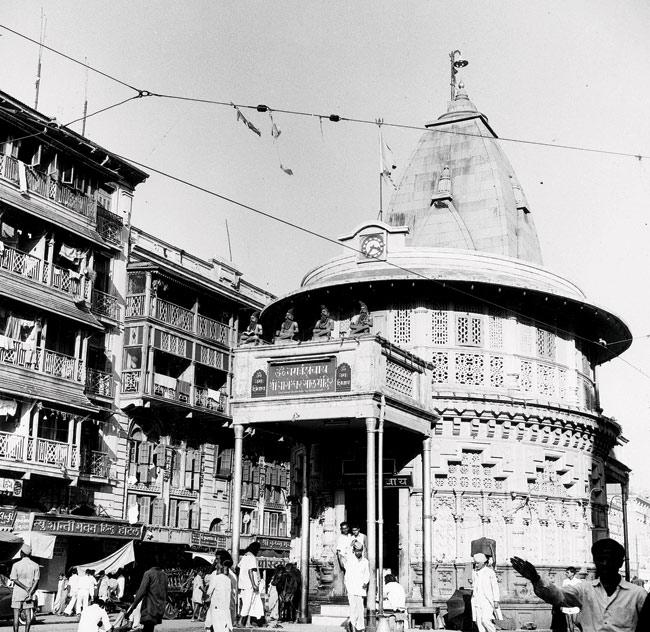

Brabourne Stadium

It’s strange to be ancient. I’ve lived in Bombay in the Forties, when a pound of beef set you back by four annas, as did the taxi’s flag drop. The small cab was an Austin or Morris, and the big one a Parsee-driven Chevy that cost six annas a ride. Occasionally, we rode in the horse-drawn Victoria, a favorite of Gujaratis, or by tram on a two-anna ticket for the Fort-Byculla-Dadar run.

Pitch perfect: Goan cricketer Tony de Mello was the soul and spirit behind the construction of Brabourne Stadium

By the early Sixties, trams were replaced by Czech-made Skoda trolley buses that ran on electricity. That was the first of the three bankrupt socialist decades that produced barter deals with Commies, and the export of a newly destitute middle class to the West. Cilicia, Caledonia and Circassia did a three-week shuttle to Southampton. Bunk fare was six hundred rupees —hot showers and commode toilets included — a culture shock to even our Eurasians who would entirely abandon Love Lane and Nagpada by the Seventies. When the British India Steam Navigation Company closed the coastal shipping service, Goa’s Chowgule stepped in with two speedier ships, Konkan Sevak and Shakti. They were built in Yugoslavia and bartered for tea and bananas.

Waves of nostalgia: The Konkan Shakti, one of two passenger steamers operated by Chowgule-owned Mogul Line

It was the time when we were forbidden from speaking Hindi at home, till Dilip Kumar’s Azad came on the scene and the whole country began to hum the film’s haunting theme song, appropriated from Verdi’s Spring. Suddenly, the language of the people we’d disdained became respectable.

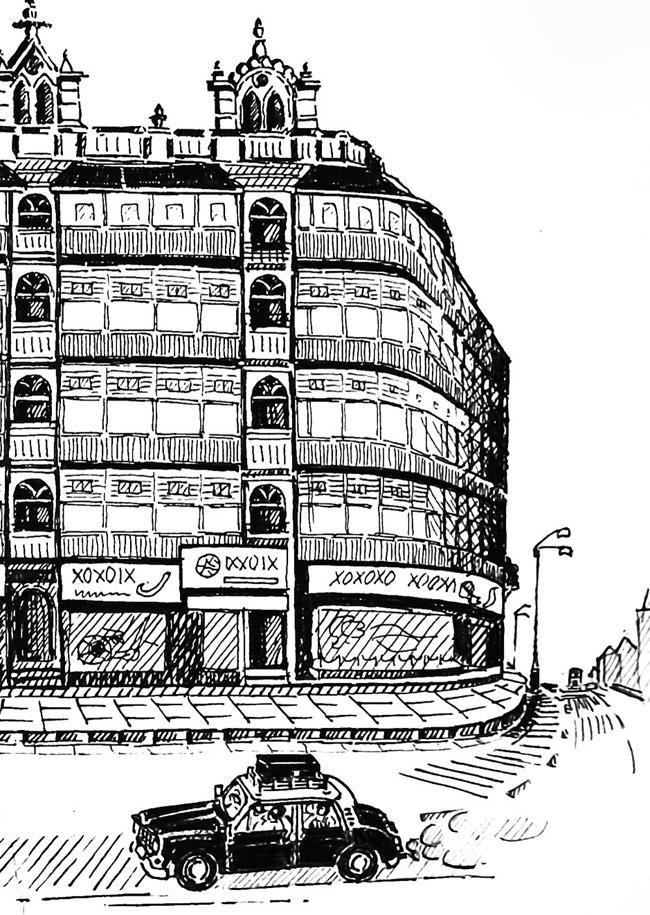

Club street: Ramesh Date’s illustration of Jer Mahal at Dhobi Talao, home to many Goan clubs

As a six-year-old, I was sent to the Bohri shop with four annas and a warning not to accept the Jap colouring box. “Say English doh (Give English),” instructed the mother. Doh was perhaps my first Hindi word taught by my mother, whose favourite phrase was “those good times before the war or these rotten times after.” But life, as in food, was cheap and good.

Days of yore: Memories, like photographs, are black-and-white. PIC/GETTY IMAGES

In the Fifties, we went to Gourdon’s on Churchgate Street, for a nine-rupee five course meal cooked and served by Goans. The owner, Emile Gourdon, one of the small band of European First World War veterans who stayed on in the East. He was the honorary secretary of the venerable Bombay Provincial Hockey Association (BPHA) and took his job very seriously, keeping a gimlet eye on playing styles. Since the gay Thirties, Emile had used his French culinary skills to cater to an eager British clientele and Bombay’s small South African crowd of Indian origin.

Inspiration: Cricketer Anthony (Tony) D'Mello

Across the road from the JJ Hospital, was Goan food at Carmello Caterers, owned by Carmello De Mello. It was a lifesaver for students of the Grant Medical College, and my batchmates of the Sixties, some 200 Malay and Southeast Africans of Indian origin, escaped to it almost daily for pulao and baffad (roast).

Bomoicar: Stories of Bombay Goans, 1930-1980 Published by Goa 1556, 154 pages Price R 200

Bomoicar: Stories of Bombay Goans, 1930-1980 Published by Goa 1556, 154 pages Price R 200

In the Seventies, there was a choice of about a dozen Goan restaurants, the special delight being Tosa’s at Kavarana Terrace on Marine Street (it has a mosque in the centre). I paid three rupees for a steak in gravy sauce — the only reason I’d want to live twice. Tosa’s was also the place to go for some hearty soups and crusty French bread served on white tablecloths.

Make me a match: Ramesh Date’s illustration, from the book, of Matchmaker Susan quizzing likely eligible prospects

My earliest recollections of Goan wedding receptions were those of small family gatherings at home. By the mid and late Fifties, parties were thrown at the Goan Institute (once Luso-Indiano), Green’s Hotel and Cowasjee Jehangir Hall on Mayo Road. Green’s was a three-storey timber structure with ribbed-wood verandah guards. CJ’s was the venue for village socials; there were prizes for being the best in class, starting at five rupees. We kids loved the upper level gallery hideout.

You knew a Goan family had arrived, when the party was at the Aldona-family owned Mac Ronnels Roof Garden in Bandra. The Aldona folk also owned the American Express Bakery chain, Vienna Hotel at Sonapur and Deluxe Hotel at Ballard Estate. Our cake came from Pierrotti’s, also called Palmer and Co., at Cumballa Hill. It was run by the affable Mr D’Cunha. Mr Pierrotti, who was about 90 when he retired in 1958, had worked as a pastry chef with the Scotsman, Mr Palmer, whom my parents had known in the Thirties.

At home, new milk pudding was a popular dessert. On cold nights we ate ginger-in-syrup sold in English crocks or stone jars, at Parsee stores. Our folks had introduced Parsees to Goan cuisine, and their cookbooks were replete with Goan recipes. But during Prohibition, Parsee bar operators with names like Toddywalla, Ginwalla and Batliwalla, upset at being upstaged by the Goan aunty, lumped us all as paowallahs.

But Goans were more than paowallahs and batliwallas.

Tony de Mello, the early Twentieth century Goan cricketer and president of the Board of Cricket Control of India (BCCI) from the mid Forties to the early Fifties, was the soul and spirit behind the construction of the Brabourne Stadium. India’s hockey goal man, Sacru — he dished out great sorpotel and fish curry in his City Kitchen on Mint Road — was invincible on the venerable BPHA field which saw civil war when the game was between the Punjab Police and Lusitanians — the latter found its match only in the barefoot-playing Afghan Police.

At the Cooperage, we were kept enthralled by Goans battling the traditional enemy, Mohammedan Sporting Club; and the wizardry of Neville De Souza who scored a hat-trick in the 1956 Melbourne Summer Olympics. Neville had started out playing hockey for St Xavier’s, where legions of Goans had studied under the caring stewardship of the Barcelona Jesuits and German Fathers who were deported after World War I. Father Hetting, a Dutchman who lived for his Java cigars, and Father Sarkis, an Armenian raised at the St Mary’s Orphanage in Mazagon, were other notables. My father was enrolled at St Xavier’s in 1921, at the age of 12. He spoke no English, paid not a dime in fees for ten years, and by the Fifties went on to manage Jesuit finances at HSBC.

Down the road from St Xavier’s at Crawford Market, grew a profusion of Goan households which like Bombay’s East Indian quarters had the Iberian feel of Goa. In Santacruz, Goans introduced the Italianate to Main and Central Avenues of the suburb, in the Twenties and Thirties. In 1948, a large group of them decided to invest in a venture that would build and operate rental homes for the middle-class. The share owners, a veritable who’s-who of the community, named the complex after Lord Willingdon, governor of Bombay from 1913 to 1918. To the great relief of the tenants, rents were frozen when the World War II erupted in 1939. The hapless owners passed on without collecting a cent in dividends on their investments; they had even financed the expensive drinking habits of many of our people. How sad it is to see many of these houses razed.

But above all, it hurts to remember how Bombay, my old hometown, once looked. To see it again, one would have to visit Singapore: identical architecture, a blend of Victorian and stucco, timber and mortar. It does not surprise me, as it was probably second stop for the same mix of Scotsmen and Parsees who’d built Bombay.

Eric Pinto is a retired human-issue professional, who over six decades has absorbed centuries of compressed history on the sub-continent and beyond.

This is an extract from Bomoicar, edited and compiled by Reena Martins. To get a copy, email reenamartins@hotmail.com / goa1556@gmail.com, or call 9820783290 / 9822122436.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!