What connects a forgotten stupa in Sindh, Pakistan, with CSMVS? A new book joins the dots from its fascinating, chance discovery at an ancient Buddhist site to its scientific reconstruction in the 21st century

Site view of the northwest face of the Kahu-jo-daro stupa, Mirpurkhas, Sindh, Pakistan, 5th century CE. Pic Courtesy/Archaeological Survey of India

Mirpurkhas is a commercial town in Sindh known for its Sindhri mangoes, and its busy railway junction. It’s also regarded as the gateway to Thar from the Pakistan side of the desert. Interestingly, records reveal that in ancient times, it was a key location at the trade and cultural crossroads between India, Central Asia, Afghanistan and the Middle East.

Reconstructed view of the stupa model

Reconstructed view of the stupa model

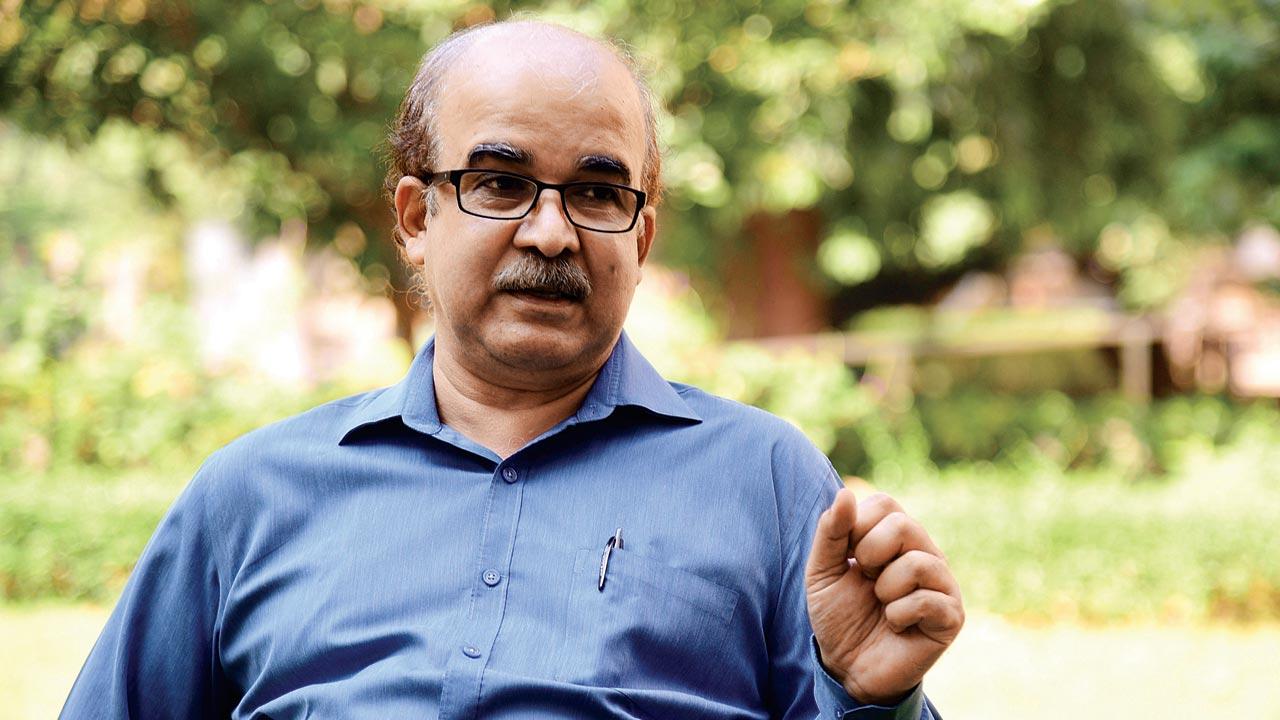

Kahu-jo-daro’s forgotten stupa in Mirpurkhas is the subject of a new, extensively documented book by Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director general, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS, formerly The Prince of Wales Museum). A popular Buddhist site that is now in ruins, The Lost Stupa of Kahu-jo-daro highlights its historic, religious and architectural significance, and explains the reconstruction of this stupa with help from excavations at the site that are part of a collection at CSMVS.

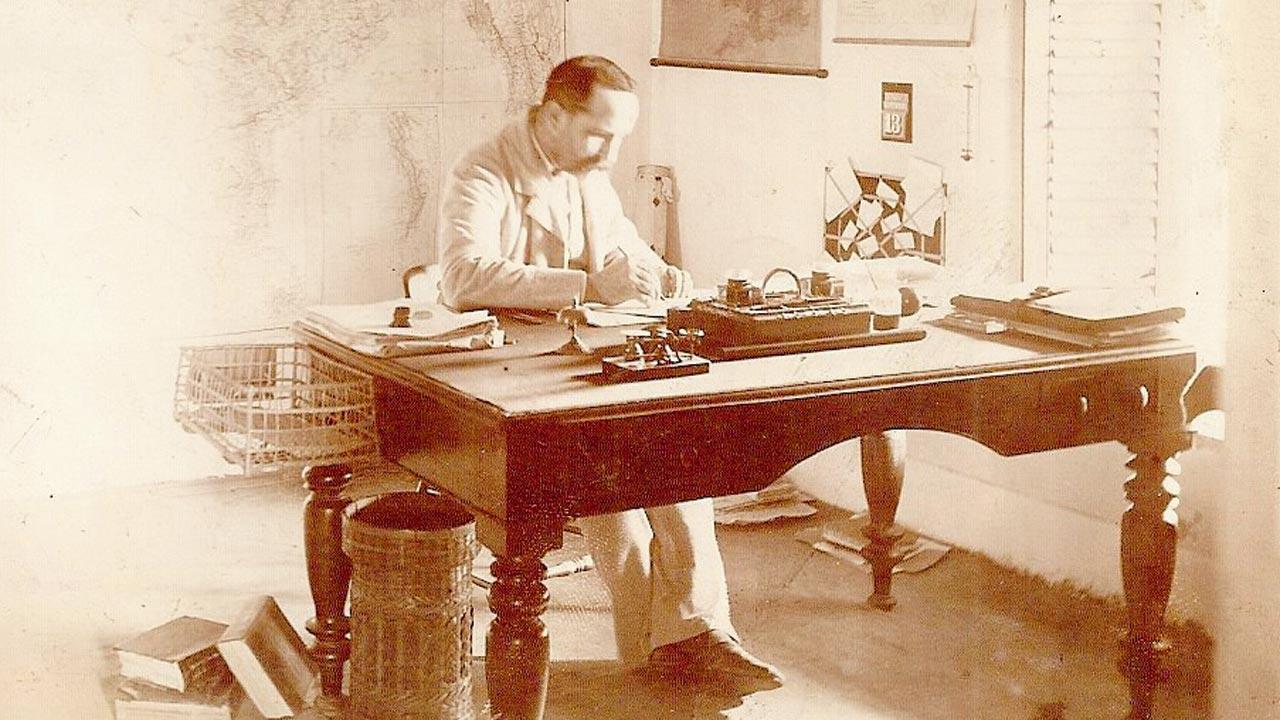

Sir Henry Cousens will always be remembered in the early history of CSMVS’s collection-building and also for his mammoth publication, The Antiquities of Sind with Historical Outline. Pic courtesy/Family of Sir Henry Cousens

Sir Henry Cousens will always be remembered in the early history of CSMVS’s collection-building and also for his mammoth publication, The Antiquities of Sind with Historical Outline. Pic courtesy/Family of Sir Henry Cousens

In the middle and late 19th century, British administrators and surveyors posted in Sindh had underestimated the historicity of the Kahu-jo-daro site [2-3 BCE; 4-5 BCE], by documenting incomplete observations of their findings. Enter archaeologist Sir Henry Cousens (1854-1933) who was the then superintendent of the Archaeological Survey (ASI), Western India. His research and vision were a godsend for Mukherjee’s book. “It was because of his extensive surveys and excavation reports [1909-10] that the cultural heritage of the long-neglected North West Province was highlighted for the first time. Being an artist and professional photographer, he created many series of architectural drawings and also captured images of sites in dilapidated condition. Some of these 100-year-old drawings and photographs of monuments in the Sindh in early 20th century [ASI archive], and more particularly, Kahu-jo-daro stupa in Mirpurkhas helped me immensely to complete my study of it from the lens of Gandhara and Kushana-Gupta art and architecture traditions,” reveals Mukherjee.

Sabyasachi Mukherjee

Sabyasachi Mukherjee

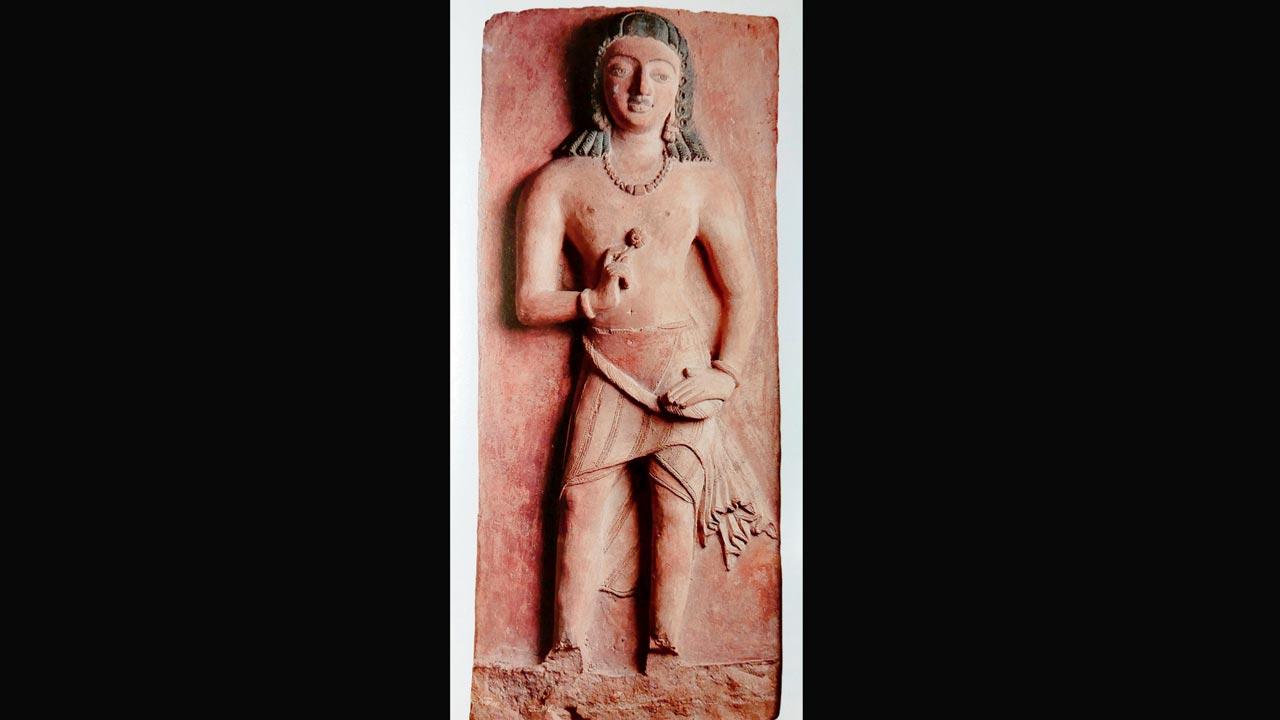

Cousens was one of the founding members of The Prince of Wales Museum. His close association with the Museum in 1905-1906, as a member of the Museum Committee, benefitted in building its archaeological collection from the North West provinces (now in Pakistan). Cousens’s vision ensured that the museum today boasts of five large seated Buddha images in high relief, a smaller image within a niche, a standing male figure (identified as a devotee), 297 moulded bricks and architectural fragments, two roundels and rectangular bricks, depicting Kubera, a few rectangular bricks bearing the image of Jambhula, sun-dried clay tablets and a tiny stone fragment of a Jataka scene.

Actual positioning of the seated Buddha; (right) Seated Buddha, Terracotta, Kahu-jo-daro stupa, Mirpurkhas, Sindh, Pakistan, 5th century CE. Pics courtesy/Archaeological Survey of India, CSMVS

Actual positioning of the seated Buddha; (right) Seated Buddha, Terracotta, Kahu-jo-daro stupa, Mirpurkhas, Sindh, Pakistan, 5th century CE. Pics courtesy/Archaeological Survey of India, CSMVS

Buddhism’s glory

Mukherjee’s interest to write this book was first piqued due to the terracotta art Kahu-jo-daro collection at CSMVS. This apart, Dr Moti Chandra’s article, A Study in the Terracotta from Mirpurkhas, inspired him to deep-dive into Buddhist architecture and the art of the site from a cultural, historic and religious standpoint. While the site was remote and beyond his reach, he had access to the Victoria & Albert Museum collection where he found the seated Buddha from the Kahu-jo-daro stupa (described as missing in the site report) and the original architectural fragments and images deposited at The Prince of Wales Museum by the excavator in 1919. Apart from those collections, his study was based on primary and secondary sources including site survey reports from the ASI, drawings and the photographs from the ASI archives.

The art of Kahu-jo-daro indicates that its artists were liberal, flexible and creative in accepting art forms and designs from the neighbouring Gandhara as well as prevalent Gupta art traditions of northern India. Pics courtesy/CSMVS

The art of Kahu-jo-daro indicates that its artists were liberal, flexible and creative in accepting art forms and designs from the neighbouring Gandhara as well as prevalent Gupta art traditions of northern India. Pics courtesy/CSMVS

Mukherjee’s studies explored the early history of Sindh and the roots of Buddhism in the Gandhara region as well as its influences in Sindh and its surrounding regions. However, due to limited literature on this monument, it presented challenges. Yet, the book effectively explores the impact of several Buddhist sects that were then active in this region. It traces the refined design of terracotta art in pre-Islamic Sindh monuments that was an extension of Indian-Gandhara art traditions.

Piecing it together

A key part of this book was the ambitious project to design a model of the actual stupa. To ensure historical accuracy, Mukherjee and the team at CSMVS pored over the archives to recreate the positioning of images and decorative bricks on the cylindrical dome as well as the square platform of the stupa. “It would have been difficult to imagine its original shape based on available architectural fragmentary remains in the CSMVS collection. However, interpreting these in light of other contemporary stupas such as Thul-Mir-Rukan, Jarak, Sudheran-jo-daro in Sindh, Top-Dara, TokarDara and SankarDara in Swat Valley, and Devnimori in Gujarat gave us an accurate idea of the original stupa,”

he reveals.

Historic proportions

The Kahu-jo-daro stupa has experienced layers of history since ancient times. “It unravels an astonishing story of creation, community participation, art, religion and belief. These relics serve as an extraordinary reminder of the social and cultural life of Sindh and of the invaluable artistic contribution of its inhabitants. Its unique architectural style reveals its close affinity to Western Classical, Persian, and Indian elements, which largely influenced the Gandhara and Sindh regions from the second to the fifth centuries,” he adds.

In light of this fascinating discovery, Mukherjee reminds us that its dilapidated condition and eventual complete destruction are telltale signs of political indifference and human ignorance. No sincere attempts are made by authorities across countries or civil society to preserve such cultural heritage for posterity. “Today, such preservation presents major challenges even in times of peace and prosperity,” he signs off.

At Museum Shop, CSMVS, MG Road, Fort.

297

Moulded bricks and architectural fragments in CSMVS’s collection from the North West province

Why was terracotta the preferred building material?

Merchant devotee (identity unknown), terracotta, Mirpurkhas, Sindh, Pakistan, 5th century CE. Pic courtesy/CSMVS

Merchant devotee (identity unknown), terracotta, Mirpurkhas, Sindh, Pakistan, 5th century CE. Pic courtesy/CSMVS

The hybrid art activity and material culture of this period can be described as an era of experimentalism. Some archaeologists and scholars maintain that stone would have required plenty of money and time. The people in the Gupta Age (3rd-4th century CE) might have been in a hurry to propagate their newly made discoveries in the field of clay art forms extensively and within a short time period. The region was also known for its good quality clay, and so people in Sindh found it cheaper. Evidence to highlight clay construction activity dates back to the Indus Valley Civilisation where Mohenjodaro (2,600 BCE) was predominantly built using clay bricks.

– S Mukherjee

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!