In an interview with professor-author Amar Farooqui, who recently delivered a lecture series for the Mumbai Research Centre of the Asiatic Society of Mumbai, he unravels the insightful emergence of the city as a key hub for opium trade

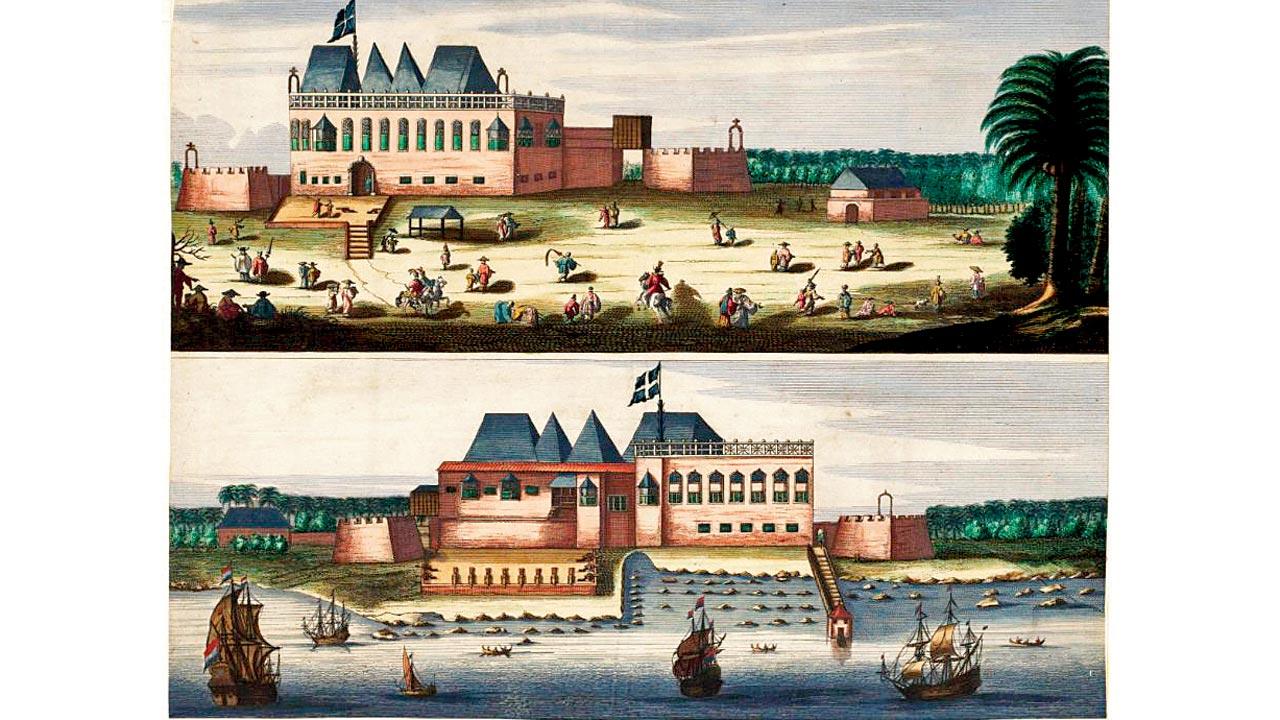

A 1665 illustration of the British East India Company’s fort at Bombay (now Mumbai) sourced from the National Archives of the Netherlands, The Hague. Pics Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons

MID-DAY: What were some of the highlights of your recently-concluded lecture series?

AMAR FAROOQUI: In an age when the trade in narcotics is internationally outlawed, and there are stringent provisions for enforcing the ban, it might seem strange that the British-Indian government promoted, and was directly involved in, the production and marketing of opium as an intoxicant for nearly 150 years. This is an aspect of colonialism that is usually ignored, and often in standard textbooks it is either completely missing or else there might be a couple of passing references to what was a pre-eminent concern of the colonial state from the 1750s onwards till almost the end of the 19th century. The first two sessions focussed on this history.

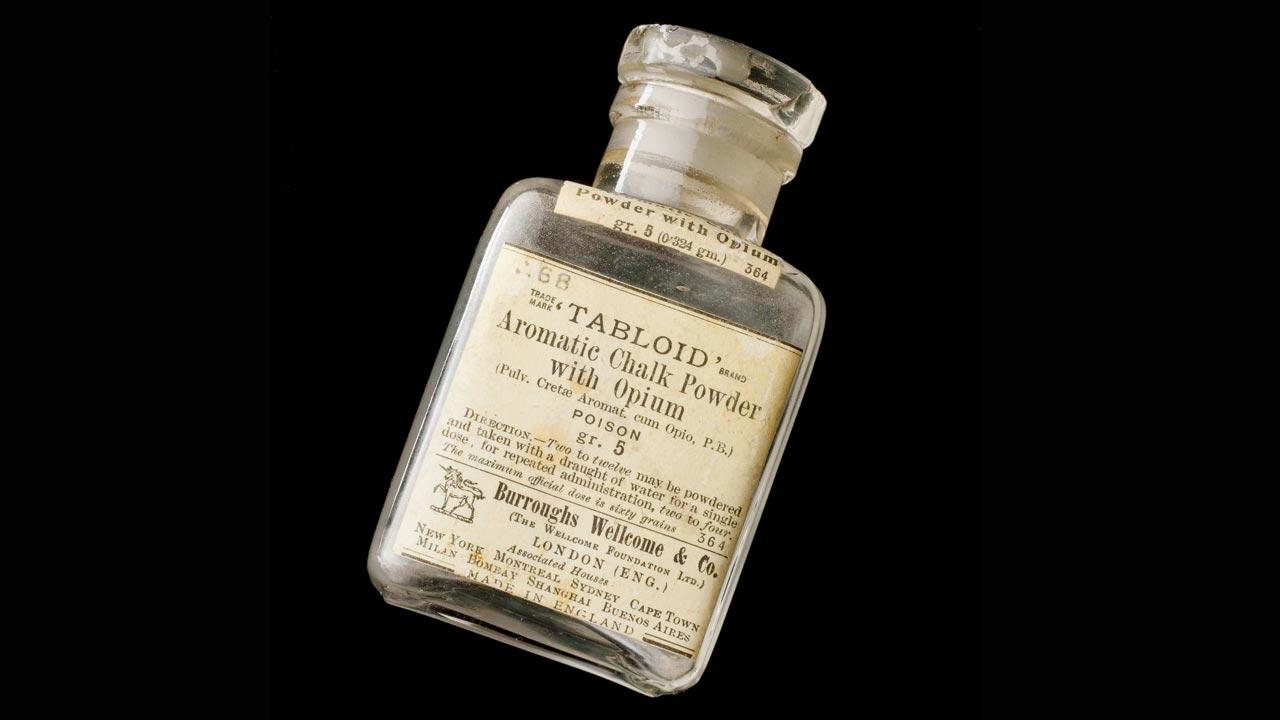

An empty bottle of aromatic chalk powder with opium manufactured by Burroughs Wellcome & Co, where the label reveals directions on how to administer a dose. Pic Courtesy/Science Museum Group; Wikimedia Commons

An empty bottle of aromatic chalk powder with opium manufactured by Burroughs Wellcome & Co, where the label reveals directions on how to administer a dose. Pic Courtesy/Science Museum Group; Wikimedia Commons

MD: Opium City (Three Essays Collective) remains one of the most insightful titles about our city’s long association with opium. What were some of the key factors that contributed towards this?

AF: Opium was a major colonial commodity, exported from India to China. China was the main market for this commodity. Towards the end of the 19th Century, particularly during the 1880s, when the exports reached their peak, almost 1,00,000 chests of opium were exported from India to China and southeast Asia annually. For the purposes of the wholesale trade, the commodity was reckoned in chests. A chest of opium contained about 60 kilos of opium.

The opium we are referring to was essentially used as an intoxicant. Opium produces very important chemicals which have significant medical uses as well. Nevertheless, the opium exported by the colonial government was not intended for medicinal purposes. It was exported primarily as an intoxicant. In other words, the British colonial government was aware that it would be used as a narcotic substance.

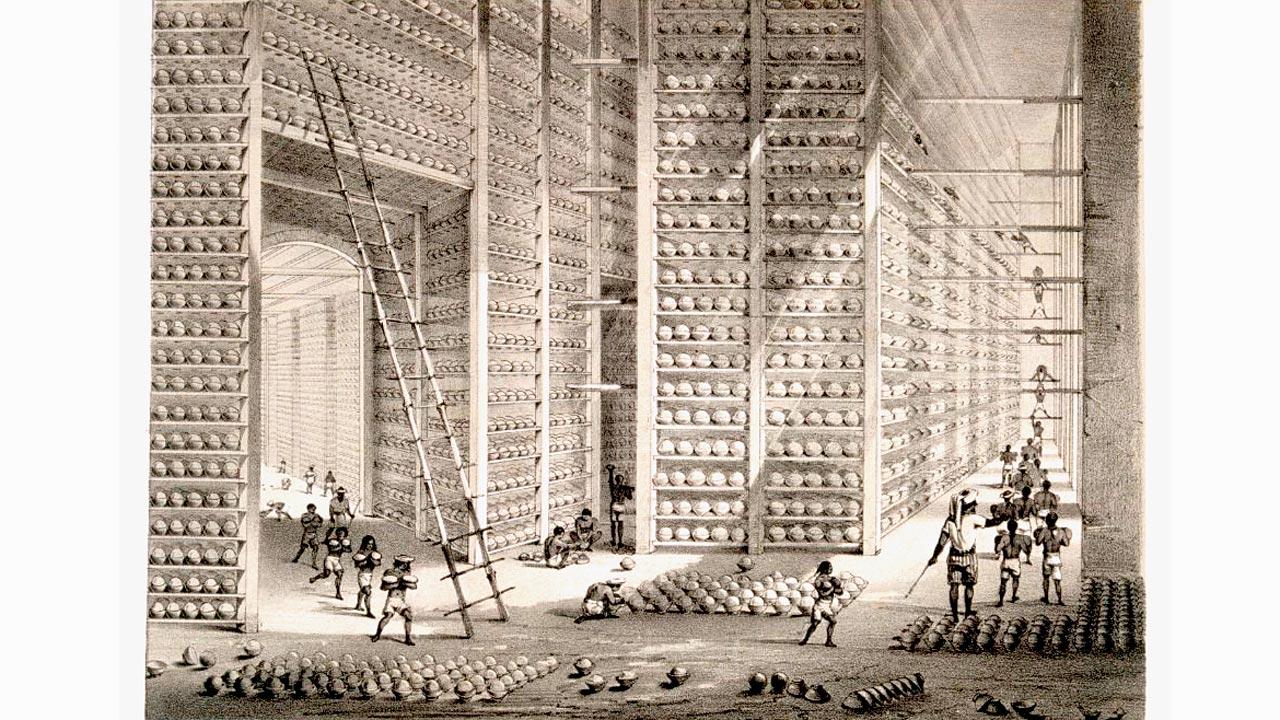

A dated lithograph by WS Shergill showing the Stacking Room inside an Opium Factory in Patna

A dated lithograph by WS Shergill showing the Stacking Room inside an Opium Factory in Patna

In the 1790s, the East India Company (EIC) imposed an official monopoly. All the opium produced in its territories in eastern India became a monopoly of the EIC. It was not just the trade in the commodity, but the production of opium too was strictly regulated by the Company.

Around the same time, EIC authorities in Calcutta (now Kolkata) were alerted to the existence of a fairly extensive trade in opium from western India. While the EIC was establishing its monopoly, there were also traders on the west coast who were tapping into commercial networks for procuring opium from central India, from the Malwa region, for export to China. These opium supplies began to threaten the EIC’s monopoly.

The Opium Clipper Brig Anonyma in the Straits of Malacca. A hand-coloured lithograph showing Anonyma in starboard-broadside view in the Strait of Malacca. It is inscribed: “The Opium Clipper Brig Anonyma (257 tons N.M.) in the Straits of Malacca, Crossing the North Sands off the 2 1/2 Fathom Bank: Dedicated to her Owners, Messrs Jardine, Matheson & Co. China; Messrs Remington & Co. Bombay, and Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, Sons & Coy, Bombay. By a late Officer of the Bombay Country Service.”

The Opium Clipper Brig Anonyma in the Straits of Malacca. A hand-coloured lithograph showing Anonyma in starboard-broadside view in the Strait of Malacca. It is inscribed: “The Opium Clipper Brig Anonyma (257 tons N.M.) in the Straits of Malacca, Crossing the North Sands off the 2 1/2 Fathom Bank: Dedicated to her Owners, Messrs Jardine, Matheson & Co. China; Messrs Remington & Co. Bombay, and Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, Sons & Coy, Bombay. By a late Officer of the Bombay Country Service.”

The failure of the British to prevent or regulate the trade on the west coast provided an opportunity to traders in the region to take away a substantial share of the profits from exports of the commodity. These traders mainly obtained their supplies from Malwa — from the princely states of central India. Eventually Bombay (now Mumbai) became the centre for the trade. The third session focussed on the implications this had for the emergence of Bombay/Mumbai as the leading urban centre of colonial India.

The transformation into one of the leading cities of the Empire occurred fairly rapidly within the space of about four decades, during the first four decades of the 19th century. Between 1800 and 1840, Bombay became a major exporter of opium and raw cotton. The role played by these two commodities in its rise of and its capitalist class is generally recognised, but the centrality of opium has not been sufficiently emphasised.

Professor Amar Farooqui

Professor Amar Farooqui

MD: Could you reveal a few fascinating discoveries in the course of your research on this subject?

AF: One of the most fascinating aspects of this history was the connection it had with the import of art objects from China to Bombay, as for example the large porcelain vases which found their way into affluent homes in the city. To a large extent these served as ballast and cargo for ships returning from the China journey. A few years ago NGMA (Mumbai) had organised an exhibition of displaying such vases and other art objects, obtained from private collections.

AVAILABLE: Bookstores and e-stores

Expert in the house

OPIUM often features in our talks and walks on old Bombay as part of our programming at The Mumbai Research Centre of the Asiatic Society of Mumbai. Professor Amar Farooqui’s name is almost synonymous with research on the opium trade, so he was our only and obvious choice for the three lectures online series on The Opium Empire. This enthralling series took participants from Malwa, to Canton and Bombay without the use of visuals, videos or PPTs. Despite it being an online lecture series, participants were able to soak in the information shared by professor Farooqui.

Shehernaz Nalwalla, vice president, The Asiatic Society of Mumbai

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!