While 88.4 lakh people with disabilities (PwD) have registered as voters for the Lok Sabha polls, we have no access to stats on those who have won seats in panchayats, Constituent Assemblies and Parliament. Why do big parties shy away from fronting a disabled neta?

Nipun Malhotra, one of the co-authors of A Charter of Demands Of, By, and For Persons with Disabilities, points out that while major political parties acknowledge religious and caste-based minorities, none have a dedicated approach to disability. Pic/Nishad Alam

From introspection to clarity, Anirban Mukherjee’s voice flits as he reflects on his years as a student active in politics, in Hooghly district—a two-hour drive from Kolkata. Since he transitioned into a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in 2010, he has actively taken part in election campaigning. “It was an era of upheaval in West Bengal, and the CPI (M) faced the brunt, a tough time to be a party member. But I remained undeterred,” says the 39-year-old government school teacher.

People outside the realm of politics expressed concern about his safety; Mukherjee has complete blindness. “But the party itself has never discriminated against me. I think a cricket analogy fittingly explains my place in it: Disabled persons in politics may be team players, but they will scarcely be made captain,” he says.

Nidhi Ashok Goyal, founder, Rising Flame

Nidhi Ashok Goyal, founder, Rising Flame

Some may say that the path for those like Mukherjee was paved by Sadhan Chandra Gupta, esteemed barrister and independent India’s first blind parliamentarian who assumed office in the 1950s. Later in his life, he also served as the Advocate General of West Bengal. “Gupta’s emergence took place at a time when a consolidated disability movement in India didn’t exist,” Mukherjee says, “He was a great orator, but his ability to make a life in politics is tied to his privileged background.

Yet, there were times when it wasn’t easy even for someone like him; when the nationalisation of the Life Insurance Corporation was being debated, a fellow parliamentarian famously made an insensitive remark about his blindness.” Like Gupta, Jaipal Reddy and Yamuna Prasad Shastri’s names are also counted in the list of veteran disabled politicians.

Arman Ali, the NCPEDP’s executive director, points out that politics is not a level playing ground for disabled candidates, across panchayat, state or national elections; Nipun Malhotra of Wheels For Life feels there is much work to be done by political parties in making space for PwDs in their manifestos. Pics/Nishad Alam

Arman Ali, the NCPEDP’s executive director, points out that politics is not a level playing ground for disabled candidates, across panchayat, state or national elections; Nipun Malhotra of Wheels For Life feels there is much work to be done by political parties in making space for PwDs in their manifestos. Pics/Nishad Alam

Seventy years have passed since Gupta first stepped into the Lok Sabha, but the list of disabled individuals who have featured prominently in Indian politics remains slim. In the run up to the 2024 Lok Sabha Elections, efforts to empower the disabled community have been focused on their rights as voters—88.4 lakh people with disabilities (PwDs) have registered—as those with over 40 per cent disability will be able to vote from home, while others from the community will be assisted with transport so that they can visit voting booths. On the other hand, the subject of PwDs’ direct participation in the capacity of politicians and future leaders was not prioritised.

As vocal organisations like the National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People (NCPEDP) call for better political inclusion, mid-day speaks to disabled individuals who have put on the neta topi, or hope to, as well as stakeholders in the community to understand the barriers disabled candidates face. Why do big parties refuse to acknowledge their potential, and why is there a dearth of statistics surrounding those who have won seats and pushed the envelope—in panchayats, the Constituent Assemblies and Parliament?

For most young people, a first, real brush with grassroots activism takes place in their college years. In the case of Kiran Nayak, a transman with an orthopaedic disability (polio), it began with a petition to make a bus stop near his college in Telangana more accessible, thereby launching his award-winning career in causes across queer and disability rights. In 2012, he founded the organisation Karnataka Vikalachetanara Sanghatane, which works with PwDs and has over 45,000 beneficiaries.

Come the 2010s, Bengaluru-based Nayak decided to turn to politics in addition to activism; he served in the staff of a transwoman who stood for local elections, and then became a member of Yogendra Yadav’s Swaraj India party. Most recently, he worked with the Indian National Congress for the 2023 Assembly Elections as a party worker. “Local governments like Janata Dal (Secular) and Bharat Rashtra Samithi reach out to the disabled community and offer support, but neither they nor major parties have fielded disabled candidates during state or national elections. This is what is preventing them from seriously examining the issues of PwDs. Having observed this treatment, I realised that in addition to raising our voices as activists, being directly involved in politics is a top priority,” says the 2020 Helen Keller awardee.

Nidhi Ashok Goyal says disabled individuals have established themselves across various fields, but are not perceived as potential leaders in politics because of prevalent social biases

Nidhi Ashok Goyal says disabled individuals have established themselves across various fields, but are not perceived as potential leaders in politics because of prevalent social biases

Could a solution include the appointment of disabled individuals to the Rajya Sabha via nomination by the President of India under Article 80? This is a point raised by the NCPEDP in its manifesto shaped by consultations with organisations and experts, PwDs, and corporates as well as engagements with politicians like P Chidambaram. The manifesto also addresses vital points like health insurance and economic participation. “It’s very important to have a seat at the table. It cannot be an afterthought,” says Arman Ali, NCPEDP’s executive director, who reiterates that disability is a political issue, “The playing field as it stands today is not level for those who are disabled. Whether it is panchayat elections or the Lok Sabha polls, mobility and resources are essential. One way to level the playing field is through the President’s nomination.”

Ali describes the ways in which campaigning spaces themselves are inaccessible, discouraging politically minded PwDs from attending events, whether it is the lack of ramps or the absence of sign language interpreters. “In fact, when the Chief Election Commissioner addressed the country last week, even his announcements were not accompanied by an ISL interpreter,” he says. Ali adds that it is regrettable that when Manmohan Singh arrived in parliament in a wheelchair in August 2023, the inaccessibility of the parliament floor did not allow for him to occupy a more central position (as per the protocol).

“Disability is mentioned in a tokenistic manner in political manifestos; it doesn’t feature in debates or speeches, or even the agendas of political leaders as they get elected,” says Nipun Malhotra, one of the co-authors of A Charter of Demands Of, By, and For Persons with Disabilities put together through consultations with rights activists, experts and PwDs across the country. Among these demands is improving the community’s political representation. He highlights that while every major political party in the country has acknowledged religious- and caste-based minorities, none of them has a dedicated approach to disability.

Overseas, PwDs enjoy fairer—but far from ideal—representation. In the US, for example, roughly 3,793 of the 36,779 elected officials had a disability, as per a 2019

report. In January 2024, Spain made history as the first person with Down’s Syndrome was elected to its parliament.

In the past, Karn Shah has refused to join a political party when it offered a tokenistic approach to making civic services accessible, as opposed to an earnest effort. Pic/Sameer Markande

In the past, Karn Shah has refused to join a political party when it offered a tokenistic approach to making civic services accessible, as opposed to an earnest effort. Pic/Sameer Markande

Persons with disabilities are gatekept from the political arena not just as candidates or party workers, but also as supporters. In April 2023, at a campaign in support of AAP’s Benguluru candidate Brijesh Kalappa, 50 persons who were wheelchair users in attendance were stopped by an Election Commission of India authority. Though the AAP said it had sought permission for the presence of disabled individuals, the reasons for the pushback cited were that wheelchairs are “vehicles”. “I have a PIL in the Supreme Court questioning the GST rates applicable to disability aids, which are taxed at five per cent,” Malhotra explains, “I always say that a wheelchair is not akin to a car, it is an aid that allows one to move, just as a hearing aid allows one to listen. The GST on wheelchairs is like a tax on someone walking If you’re not permitting wheelchairs at a show of support or protest, it’s like asking someone to arrive without their legs.”

Nidhi Ashok Goyal, founder and executive director of Rising Flame, highlights how disabled individuals have achieved expertise and earned laurels across fields, from medicine to finance and law, but are still seen as recipients of charity and care. “If you can trust disabled people with your bodies, money and legal cases, why aren’t you trusting them with the running of the country? It’s because PwDs are perceived a certain way… Consider how at conferences, even if we are established subject matter experts, we are still assigned to panels on diversity and inclusion. We’re seen not as experts in our fields, but rather our disabilities,” she says.

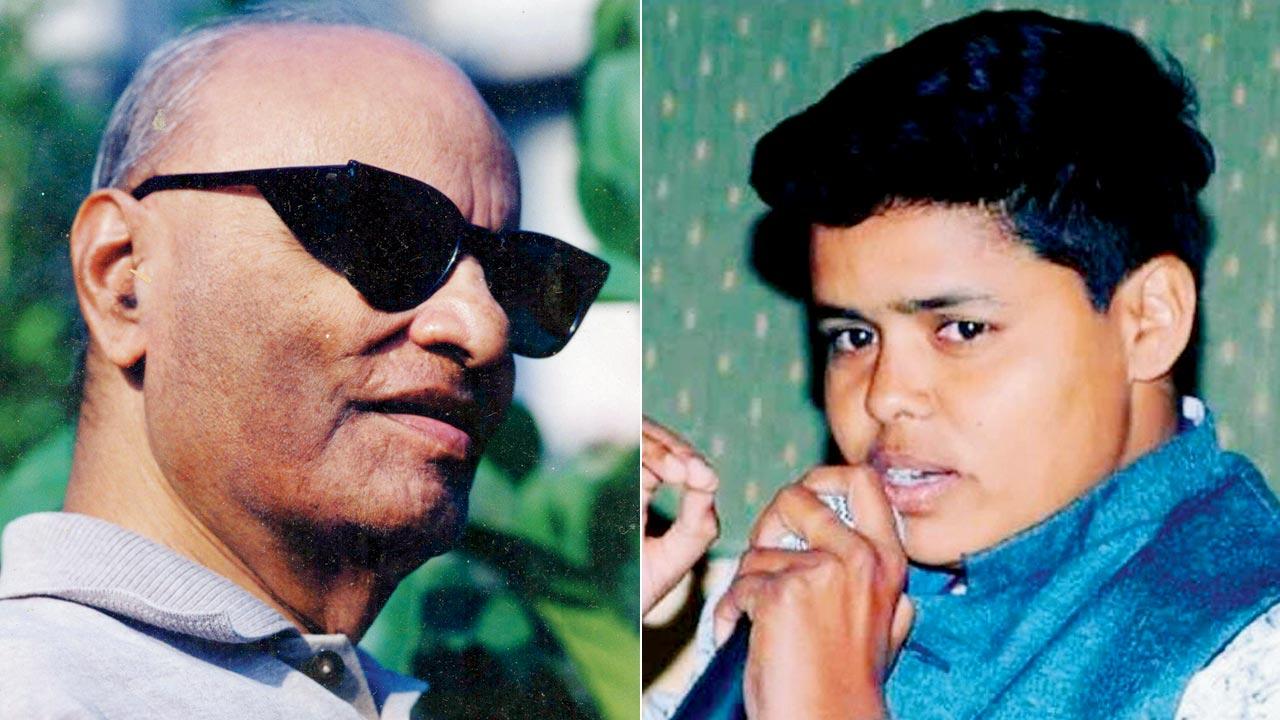

Sadhan Gupta and Kiran Nayak

Sadhan Gupta and Kiran Nayak

The bias against disabled individuals also has much to do with the conventional, able-bodied understanding and images of leadership—of what a voter and politician looks like. “Social mindsets stop people from looking at us PwDs as leaders who are capable of guiding, influencing others—as people with autonomous voices and decision-making skills. We are seen as only receivers of care and not as equal citizens holding capacity and knowledge to lead political processes or even make a difference there,” Goyal explains. Many images of leaders across public life, business and governance feature men—a stereotype that also seeps into disability discourse.

“By not having disabled individuals in the political arena, what we’re also saying is that we don’t care about this community,” says Goyal, “PwDs are also not seen as a vote bank or contributors to the economy… It is imperative to ask what the effects of this systemic de-prioritisation will be.”

He was all of 10 when Karn Shah, a canine and feline behaviourist and “sit down” comedian, had his first brush with civic and political engagement. The Dadar resident and his elder brother Mihir long dreamed of visiting Shivaji Park together, but the closure of large gates which could have allowed Shah, a motorised wheelchair user, to enter, stood quite literally in the way. On an unusual day when they spotted a lone gate open and decided to venture forth, a policeman stationed nearby stopped the duo, warning them that no cars or vehicles are allowed inside. Shah’s disabled brother approached Raj Thackeray, who lived nearby, and confronted him about the problem; to his surprise, the iconic park was made wheelchair friendly within no time. The result of his determination continues to be felt today—as the park has become more accessible to wheelchair users.

The incident firmly shaped Shah’s understanding of the power that lay in his hands. In 2018-19, he brought attention to the inaccessibility of Sulabh shauchalayas [public toilets] in the city through a social media post, which drew the attention of residents, the media and a number of political parties. It led him to cross paths with a political party which offered to improve the state of sanitation for disabled people, but only through a quid pro quo arrangement with Shah. “One party came forward and asked me to join their cadre when I offered suggestions about the toilets. I refused, because I wasn’t interested in joining politics at the time, but also because they would not enact change unless I credited it to them and joined their ranks. My own name would find no mention. Their intent was tokenistic and far from noble; if they had agreed to undertake a pan-Mumbai transformation, I may have still considered their offer,” says Shah, who has Spinal Muscular Atrophy.

The disability rights activist says that there is a need for a party by the disabled, for the disabled, which centres their needs. “Disability can happen to anyone at any time; they aren’t just congenital. Benefits for PwDs, such as accessible roads and footpaths as mandated by the law exist only on paper; the ground reality is that you will hardly find disabled-friendly public or private spaces. Though authorities in Mumbai may not pay heed to our voices, I think we can make a better case for ourselves if we go to Delhi and put forth our demands. I wonder whether a party like this would help implement old laws for disabled individuals with a new rigour,” says Shah.

Shah’s vision for a PwD-only party seems especially crucial when juxtaposed with the experiences of Shashank Pandey, who spent a year working for a Lok Sabha MP as part of a Legislative Assistants to Members of Parliament fellowship. Over the course of a year, what struck him as someone who has low vision (50 per cent disability) was the absence of visibly disabled representatives. “The other gap was that discourse on disability was missing at the top-most level of the legislative body. I’ve seen advancements in education, employment and infrastructure, even skill development, but politics is never presented as a choice to disabled individuals,” says Pandey, who is the founder of the Politics and Disability Forum. “There’s an assumption that the disabled community is only concerned with the basic necessities. They are not seen as a collective which can have political power—this is an invisibility of disability.”

One of the focus areas of Pandey’s independent research is the lack of data about disabled legislators, at the state and national levels. “The nomination forms and affidavits filed by candidates during elections don’t have a column on disability. This is not the case when it comes to other factors like gender and caste,” he notes. As part of the Javed Abidi Fellowship on Disability by the NCPEDP, Pandey surveyed 42 PwDs and analysed their responses for a baseline report on the political participation of the community. “The absence of opportunities is a systemic flaw which runs in circles wherein top leadership doesn’t identify PwDs since they are not visible in the party cadre and PwDs don’t join the party cadre as they don’t see any PwD at higher position in political space,” Pandey writes in this report.

Aside from the absence of community role models in politics, rules and regulations themselves can prove to be a barrier. In 2011, the nomination papers filed by deaf tailor T Kavitha were rejected by officials citing election rules about deaf-mute individuals; a decade later, she contested as a candidate from the same ward. More recently, in 2018, a visually impaired candidate’s application to a local loan co-operative society was rejected because he could read and write in Braille, and not Tamil or English. “The Constitution, for example, uses the term ‘unsound mind’, and courts have tried to define who a person with an unsound mind is—these people are not allowed to contest elections. Any person with a mental or intellectual disability could be termed as being of unsound mind; whether it is true

or not is a subjective matter,” Pandey explains.

As the community watches the Lok Sabha elections unfold, many remain hopeful of a future where, like Shah imagines, they will see themselves in the leaders who shape the country. “There was a saying in the Western world about the disability movement, ‘Nothing about us without us’. Many have pointed out that a better version of this motto is ‘Nothing without us’. There’s nothing more superior than lived experiences,” Malhotra fittingly says.

88.4 L

No. of disabled voters registered for 2024 LS polls

The ground reality

A baseline report on the political participation of disabled people by Shashank Pandey under the Javed Abidi Fellowship on Disability (NCPEDP) analysed the survey responses of 42 participants

71%

No. of respondents who said they have never attended an event about the political participation of the disabled in India

93%

No. of respondents who informed that they were not part of a political organisation

25%

No. of respondents who see themselves being elected to politics

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!