Author Manu Joseph, in his debut in literary non-fiction, ponders on a question we don’t like to think about — Why The Poor Don’t Kill Us

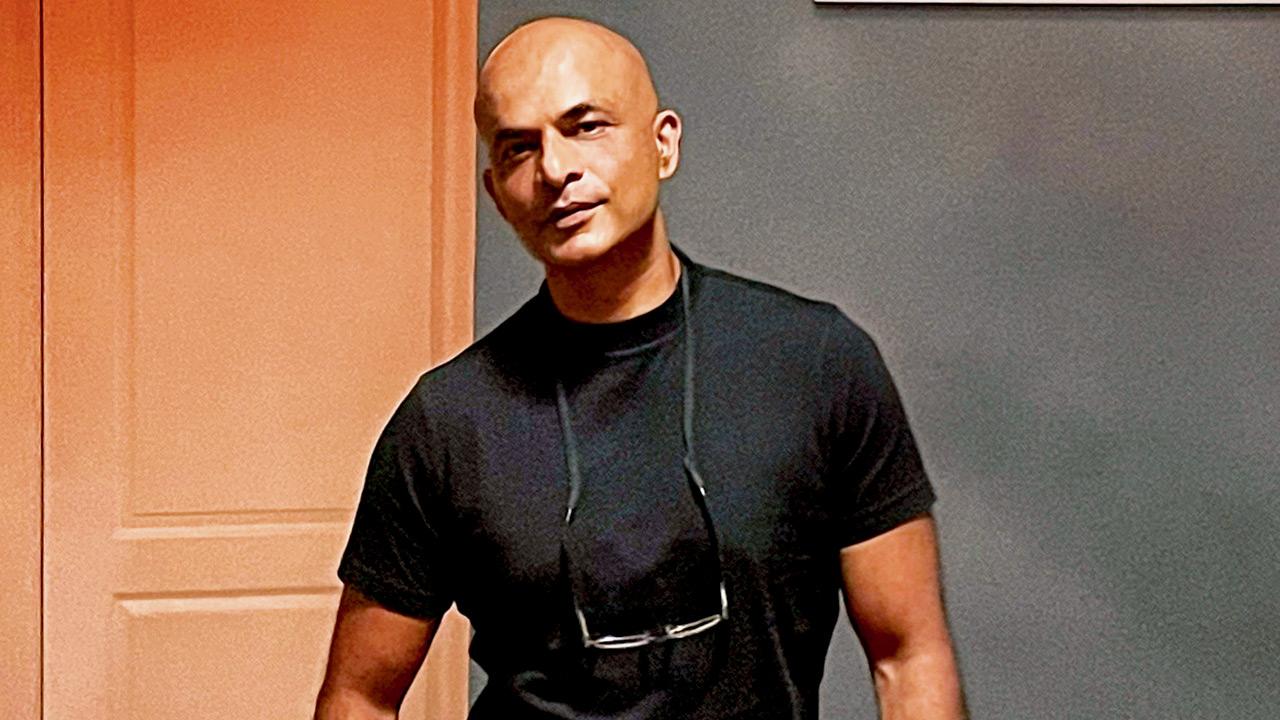

Manu Joseph, whose new book marks his debut in non-fiction, after the success of novels such as Serious Men and The Illicit Happiness of Other People. Pic/Rohit Chawla

What is it like to be poor in this country? It’s a question the middle and upper classes studiously avoid thinking about as we spend more on a pair of sneakers than a domestic worker might make after three months of back-breaking labour. If we confronted this uncomfortable truth, of course, we’d be forced to ask the next question — why don’t the poor rise up and kill us?

But author Manu Joseph has never been one to turn away from bleak truths, either in his years as a journalist, or his novels, Serious Men and The Illicit Happiness of Other People. In his latest release, Why The Poor Don’t Kill Us: The Psychology of Indians — his debut in non-fiction literature — Joseph brings his trademark dark humour and biting commentary on the dysfunction of Indian society as he seeks to explore the titular question.

Some contrast photography conveys the vulgarity of the wealth disparity, says Manu Joseph, such as a beggar outside the luxurious Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in Colaba, or the disparity between the city’s chawls and its glass skyscrapers, standing cheek by jowl. Pics/Getty Images

Some contrast photography conveys the vulgarity of the wealth disparity, says Manu Joseph, such as a beggar outside the luxurious Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in Colaba, or the disparity between the city’s chawls and its glass skyscrapers, standing cheek by jowl. Pics/Getty Images

What sparked the query in his mind, we ask the Gurugram-based author on a phone call. “In July 2017, some maids and their men attacked a housing society in Noida. A young maid had gone missing and the mob suspected that a family in the society had detained her and accused her of stealing money,” he recalls, “It’s not something you imagine happening in India, where the working class is so servile. But I’ve seen more signs of it recently, such as maids talking back to employers, and security guards’ attitudes changing.” Rare as the Noida incident was, it did not shock Joseph. “What is surprising is why they do not attack more often,” he says.

Before you get a bucket of popcorn to enjoy a takedown — only in the literary sense, of course — of the country’s billionaires, a little heads up: This book is not about them; it’s about us. It’s about the urban middle class that likes, as Manu puts it so succinctly, to use the poor as a moral pedestal to stand on and accuse billionaires of vulgar wealth. And yet, he points out that to the poor, “It’s the middle class that is the most visible section of ‘the rich’”. Why would a poor person care more about Mukesh Ambani’s 27-storey home at Altamont Road — Mumbai’s “Billionaires’ Row” — more than author-activist and friend-to-the-disenfranchised Arundhati Roy’s home in Delhi’s posh Jor Bagh locality, he questions.

Joseph himself is not exempt from his unflinching observation. “Many times, my Zomato order is more than my maid’s monthly pay,” he writes honestly, “and I have developed the habit of snatching the parcel before she can see the bill.” The income divide is so wide, the rich and poor are like “people from two different countries living side by side”, he says, reminding us instantly of the controversy comedian Vir Das had invited on his “Two Indias” bit. Many weighs in, “I don’t know what the fuss was all about. Nobody who lives in India can deny this [disparity].”

The book is a gut punch from the very first chapter, where Joseph takes us to Gujarat, in the aftermath of the 2001 earthquake. As a reporter on the scene, he recalls seeing men numbly trying to salvage whatever belongings they could after realising they had lost their entire family. When all is lost, the only thing one can afford is to move on. “The poor don’t need a natural disaster to be this way,” he tell us, “That’s what poverty does; it breeds this sort of feral pragmatism. Living in poverty is living in a state of just constantly accepting catastrophe, and that you don’t have any control over your misfortunes.”

Living in constant survival mode, “poor people are like our prehistoric ancestors”, says Joseph, “poverty puts them decades or centuries behind the rest of civilisation”. To this scribe, reading Joseph’s book feels a bit like trying to ride the Mumbai local train in rush hour. It’s utterly miserable at times, but the author’s unflinching commentary on society compels you to keep reading. Is there hope at the end of the journey?

Not if you go by the title of the last chapter — Inequality Cannot Be Solved. But Joseph is not here to comfort us. He’s here to hold up a mirror to just how hypocritical and exploitative we are in our privilege. We celebrate ads that talk about treating domestic staff with dignity, but balk when the cleaner asks for leave. We argue against any hikes in their meagre salaries, while spending more on our pets than their entire budget to run their entire household for the month.

Joseph, though, places his hope in an unexpected quarter. “I see hope in politics. It is in the interest of politicians – who are entrepreneurs — to give a few things to the people,” he says. He foresees rising tensions as the nation grows more prosperous, though. “A Tamil leader had once told the poor that they are poor because of the sins of past lives. There might have been one man in the crowd who stood up and objected to that statement. But with more awareness comes anger.

“In the slums, many make peace with their situation, because this is all they have known. But there are always a few who want to be something more. And they are the one who are miserable, because they realise that the system of progress that society has claimed is bogus. It’s not like you go to college and do well and then the doors open. The doors are held shut by the privileged club. But with time, people are not going to be so forgiving of opportunities they don’t have. It’s easier to be poor in a poor country, than poor in a rich country,” he says.

On the voter fraud controversy

Unlike so many of his ilk, journalist and author Manu Joseph holds faith in Indian politics and democracy as one avenue of succour to the poor. While on the subject, we ask him what he thinks of the voter fraud allegations levelled by Rahul Gandhi recently.

As always, Manu’s perspective is different from the masses: “The most interesting thing to me is that he chose a press conference [to break the news]. In another time, even 10 years ago, like with the Radia tapes controversy, he would have given the information to a trusted journalist and then it would have been an exclusive cover story. That is how stories broke before. Now, there is no such thing as trusted free media anymore.”

As far as where he stands on it, he says bluntly, “Intuitively, I find it hard to believe that BJP is not as popular as the elections make them out to be. But journalists are checking the veracity of some of the claims; let’s see how far the story goes and what comes out of it.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!