From unfamiliar streets to new syllabuses, expat parents share how they navigate a fresh start in Mumbai

Keiko Matsubara with her three children, navigating a new city, language, and school system after their move from Japan to Mumbai in May. PIC/ATUL KAMBLE

When Keiko Matsubara’s family moved from Japan to Mumbai in May, they knew the transition wouldn’t be simple. A new city, a new language, and a new school system for their three children (ages 10, 7 and 4) — especially the younger two who spoke little English — felt like a steep hill to climb. “There were gestures and ways of communicating that felt unfamiliar,” says Keiko Matsubara. “In Japan, so much is understood without words. Here, you need to ask questions, provide explanations, and follow up. It took some getting used to, but we adapted.”

Cultural adaptation, emotional adjustment, climate shifts, and building relationships from scratch can overwhelm expat families. “I’ve seen families feel completely lost — from navigating the city to figuring out where to buy groceries,” says Fatema Agarkar, Educationist, School Board Advisor and Mentor to Finland International School (FIS). Her son has studied alongside international families and often heard how hard it was to break the ice. Yet, she adds, Mumbai’s melting pot spirit shines through. “It’s a city that welcomes.”

For Andreas, Sevda, and their daughter Veronika Bruckl, a new country meant navigating unfamiliar systems, from curriculum to calendars

What made a big difference for the Matsubaras was the community. “The Japanese moms were incredible,” says Keiko Matsubara, adding, “Even before we joined the school, they were sharing tips and reassuring us. After admission, parents from our class reached out with helpful information. It was such a relief,” she says. Choosing to live in an apartment complex with other expat families — both Japanese and non-Japanese — was also intentional. “That mix helped us feel less alone.”

For the Bruckls from Oshiwara, too, a new country, unfamiliar systems — everything from curriculum structure, to teaching style and academic calendars — felt different. Dad Andreas Gerhard Bruckl is German, and his wife Sevda is Turkish. Their daughter Veronika is moving from Sr Kg to Grade I in 2025-26 at JBCN International School, Oshiwara. “We weren’t just looking for academic alignment; we wanted a space where our child could thrive emotionally and culturally, too,” says Andreas.

Academically, the Matsubara family was navigating unfamiliar waters. “The grade and age cutoffs were different from Japan, but that wasn’t too hard to manage. I’m still learning what’s expected here academically,” Matsubara admits, “but it hasn’t felt overwhelming.”

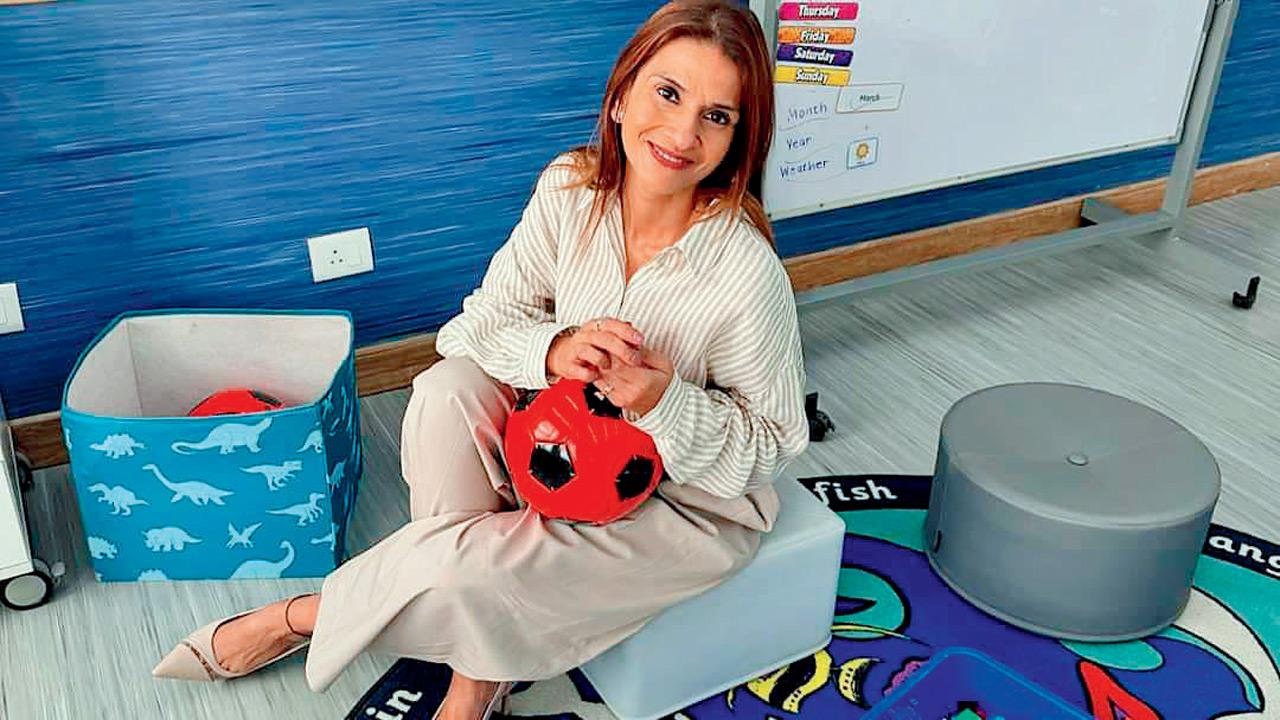

Fatema Agarkar admits that breaking the ice may not be easy but Mumbai’s welcoming, melting-pot spirit soon takes over

The family chose FIS, a school with a small, diverse student body. “Even among Indian students, many have lived abroad. That blend of backgrounds made us feel we weren’t the only new ones trying to find our place.” The school supported their transition through clear communication — WhatsApp, email, and an app that shared classroom work and updates. Trial classes and a detailed walkthrough helped the children gain confidence before formally joining. “Other Japanese students who already spoke English helped our kids adjust. That peer support meant a lot,” she adds.

In a surprising twist, the move lifted a burden for their eldest. “She had been under a lot of pressure preparing for junior high school entrance exams in Japan. Here, she’s able to study what interests her, without cram school (a private institution that provides intensive tutoring and exam preparation). It’s a relief,” says Matsubara.

School lunch was one of the early cultural bumps. “Some dishes were spicy at first, so the school allowed us to send home-packed tiffins,” she smiles. “But eventually, my kids wanted to try what others were eating.” Reflecting on the journey, she says, “The transition wasn’t easy, but the warmth of the community and the school made it better than we imagined. We didn’t just move countries — we found new rhythms, new support, and new friends.”

Stephen James Tumpane

At FIS, transition support is central. From trial classes and multilingual assistance to cultural clubs and hands-on staff, every family gets tailored help. “We preempt needs — from transport and uniforms to financial support — so families always have a go-to person,” Agarkar says. Community is key, and the cultural fusion extends beyond classrooms — every festival is marked, from Diwali to Japanese Mother’s Café, with food, music, books, and storytelling. Field trips to Japan and Finland, along with guest speakers from consulates, bring global learning to life.

Mental health is also a priority. Through Switch for Schools, an Australian emotional wellness program, FIS tracks daily emotional shifts. During one visit, the Consul General of Finland noted how Japanese families in the community felt so at ease that it hardly seemed like they were living abroad. This, says Agarkar, reflects what international education in India can aspire to be — helping both expat and local families navigate change with greater ease.

At JBCN International School’s five branches — Parel, Oshiwara, Borivli, Chembur, and Mulund — personalised onboarding, buddy programmes, and cultural familiarisation events help new learners and parents settle in with ease. Coffee mornings, family days, and community circles turn introductions into friendships, and friendships into a sense of belonging.

“The first thing we focus on is belonging,” says Stephen James Tumpane, Principal, JBCN International School, Oshiwara. “If a child and their parents feel part of the community, learning follows naturally.” For the Bruckls, the experience was immediate. “From the first week, she had a buddy showing her around, and we were meeting other parents over coffee. It felt less like starting over and more like joining an extended family,” says Andreas.

Adapting to a new school in a new country can be daunting, but the Bruckls found the transition seamless. “Veronika settled in far quicker than we imagined. Our only real challenge has been keeping up with all the playdates,” laughs Sevda. They credit the warm parent community, active WhatsApp groups, and open communication with making them feel instantly included. “I’ve already attended more school events here than my parents did in my entire schooling,” says Andreas.

Social-emotional learning is embedded from the early years through initiatives like Rainbow Week and empathy campaigns. “Happy educators create happy classrooms,” says Tumpane, noting that staff wellness is as much a priority as student wellbeing. For the Bruckls, that philosophy has been more than words. “We’ve never felt like just another family on the list,” says Sevda. “Here, you’re seen, you’re heard, and you’re part of something bigger.”

Not every expat family gets the cushion of an international school. For some, the landing is more challenging, the learning curve steeper, and the safety net non-existent. An American mother and Indian father, who moved with their three children to India and chose a non-IB curriculum, have not had it as easy. The mother, who wishes for the family to remain unnamed, says that while her daughters were young, the bigger adjustment they faced when they moved was understanding how different the system here is. “In the US, most families send their children to excellent public schools. Private schools were rare, and when I was growing up, they were usually for the wealthy or for kids who needed a different environment.

Here, education feels more like survival of the fittest — an intense curriculum and high-stakes exams. We’re just trying to make sure our kids keep their childhood intact while navigating it.” Socially, her children love their school and haven’t had challenges fitting in. But academically, there’s a steep learning curve, especially in subjects like Hindi. “In the US, if a child needs extra help, the school steps in — there are support classes and specialised teachers. Here, the responsibility falls squarely on parents. The school partners with you to close learning gaps; here, it’s up to the parents to make it happen. That changes your role completely, but it also teaches you to be resourceful and proactive. Hindi is taught as a first language, even for non-native speakers, which makes it tough for newcomers.”

While the school’s communication is straightforward and they meet with the counsellor when needed, parts of the system are hard to understand. “Much of the teaching here focuses on covering the curriculum, with the expectation that tutoring will fill the gaps. In earlier years, we had tutors for all subjects. Now, we focus on Maths and Hindi — Cuemath has worked especially well,” she adds. “Unlike international boards, there’s no expat parent network, support group, or orientation at other boards. We simply had to ‘jump on the train’ and keep up.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!