Parents hope sole English school in Satara’s Jawali taluka will open the window of opportunity for their kids, but it’s struggling to even keep its doors open

Navjeevan Vidyalaya currently only has classes up to Standard 4, but students and parents in the neighbouring villages hope this will expand to Standard 12. Pics/Nimesh Dave

In Satara’s Kudal village, closed in by hills on all sides with not even a road to connect it with the rest of the world, there are few jobs and barely any money to be made. The villagers’ ambitions for a better life for their children rest on the sole English-medium school there, aptly named Navjeevan Vidyalaya. Now even this last hope is under threat, as the self-funded private school struggles to keep its doors open amid dwindling finances.

Just 30 kms from Mahabaleshwar and 300 kms from Mumbai, Kudal village is located in the remote Jawali taluka, where most villages are not even connected by state transport bus services. As many as 50 students from neighbouring villages in a 10-km radius attend Navjeevan Vidyalaya, which currently runs classes from nursery to Standard 4.

The school has been authorised by the state education department to set up advanced classes from Standards 5 to 12, as the region doesn’t have any junior college yet. School founder Rohini Nimbalkar, however, says that not only do they lack the crores required to set up the infrastructure for senior classes, but they are not even able to keep up with their current expenses.

Work is scarce in the taluka, and most students’ parents have either moved to cities to find work as labourers, or are dependant on farming or are unemployed. Those who find work in the villages as temporary farm labourers barely take home R150-200 per day. During the monsoon and summer, they usually can’t find work. Dealt a bad hand by fate, the villagers want their children to study in an English-medium school so they have better prospects ahead, but cannot afford to pay the private school’s fees. “Whether the parents can pay or not, though, the school continues to educate the children. With no other source of funding, however, this means the school runs into losses of R12 lakh per year on average,” says Nimbalkar.

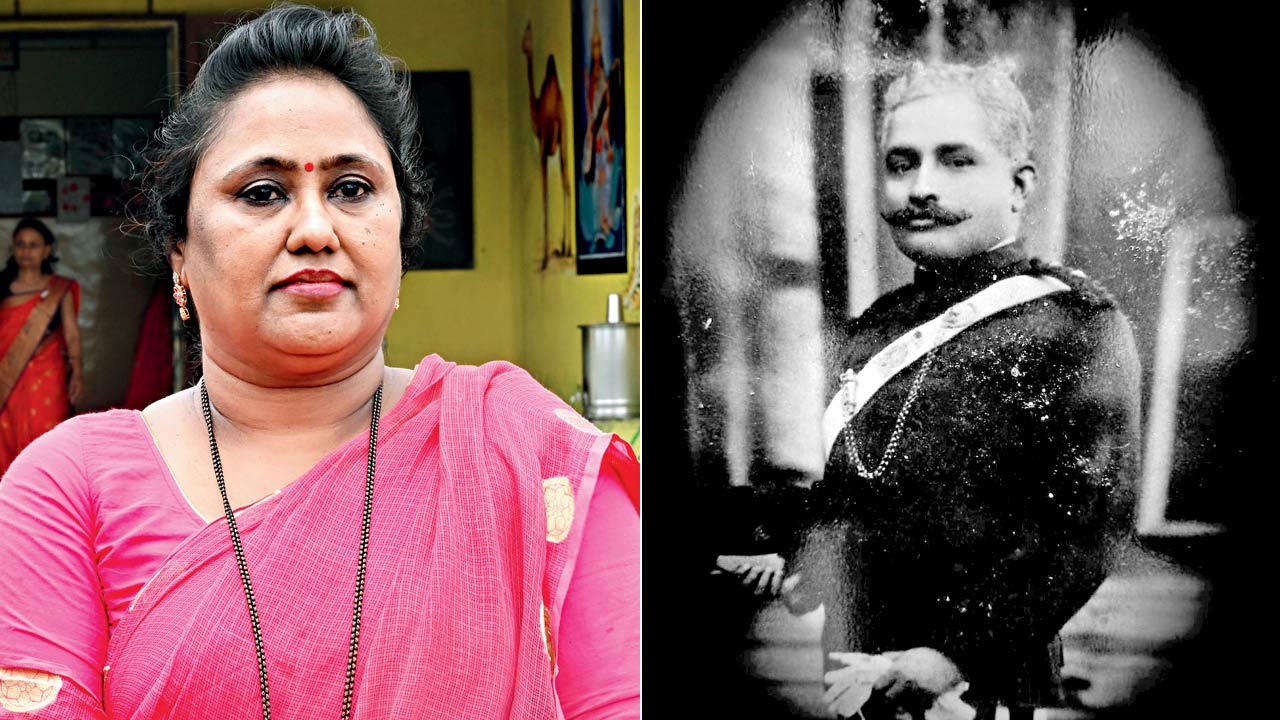

Rohini Nimbalkar, school founder; (right) Rohini Nimbalkar founded the school to fulfil the wishes of her great-grandfather Barrister Nanansaheb Sidram Shinde

Rohini Nimbalkar, school founder; (right) Rohini Nimbalkar founded the school to fulfil the wishes of her great-grandfather Barrister Nanansaheb Sidram Shinde

Nimbalkar, 51, is a double post graduate in Hindi and history, and was earlier teaching future educators in a DEd programme in Pune when she realised there was a huge disparity between candidates from urban and rural areas. Although students who hailed from rural areas had a better grasp on history, culture and civics, they were far behind urban students when it came to English and this impacted their confidence greatly. It was this disparity, as well as her great-grandfather barrister Nanansaheb Sidram Shinde’s dream to set up a school that inspired Nimbalkar to quit her job and establish Navjeevan Vidyalaya in 2007.

After initially operating the school out of her ancestral home in Jawali, she converted a ground-plus-two-storey building on her ancestral land into the school. This building was where she was previously running a training centre for a self-help group (SHG) for women from nearby villages, teaching them how to prepare homemade pickles, papad, tailoring, and household items for sale and financial empowerment. The structure was built with financial aid of R47.4 lakh from the Japanese consulate in Mumbai in 2011. Once the SHG ceased operations, the building was a clear choice for the school venue. “Despite the land being mine and the building being completely funded, I can’t keep up with other expenses that have mounted over the years,” says Nimbalkar.

Seven-year-old Sourya Parmane and his grandmother Taramati are grateful that he can continue to wear the Navjeevn Vidyalaya uniform and attend classes, despite them not being able to afford the fees

Seven-year-old Sourya Parmane and his grandmother Taramati are grateful that he can continue to wear the Navjeevn Vidyalaya uniform and attend classes, despite them not being able to afford the fees

Run under the aegis of the Akhil Maharashtra Education Society, the school’s annual expenses add up to about R14 lakh—with average costs of Rs 1 lakh per month—counting utilities, salaries and other expenses. The annual school fees per student is Rs 10,000, but most families are unable to afford that, so barely Rs 2-3 lakh trickles in as income from fees every year, says Nimbalkar.

Of the Rs 1 lakh monthly expenditure, she funds about 60 per cent from her own pocket. “Every month, my husband, an engineer, contributes Rs 10,000 from his earnings. My son adds another Rs 30,000. I put in Rs 20,000 from my soyabean farm,” she says.

Dhanashree Gaikwad (in yellow saree) rues the impact on her sons Paras and Mahi’s education after financial restraints forced her to pull them out of the English-medium school and admit them to the zilla parishad school instead

Dhanashree Gaikwad (in yellow saree) rues the impact on her sons Paras and Mahi’s education after financial restraints forced her to pull them out of the English-medium school and admit them to the zilla parishad school instead

“I have faced situations where I would not be able to pay the salary of my teachers on time, but they all stood beside me. I will put in all efforts to ensure that the school continues to exist, to uplift the future of these children,” adds the founder.

Local residents had pinned their hopes on the school expanding and offering classes up to Standard 12, as the villages do not have any junior college nearby. But this will take an investment of crores to set up laboratories and additional classrooms, says Nimbalkar, who is now considering crowdfunding to help her further develop the school.

Ujwala Pawar, Principal of zilla parishad school

Ujwala Pawar, Principal of zilla parishad school

She also hopes that a corporate sponsor might help to keep the school afloat. “In the past, the school received help from an IT firm, which donated 20 computers to us, with which we opened a computer laboratory and started imparting basic computer education to the students,” she says.

The region has a state-run zilla parishad Marathi-medium school with classes up to Standard 7 in Somardi village, Jawali taluka. It also offers English as one of the subjects, but many parents from neighbouring villages say the quality of education is sub-standard, as students struggle to even read Marathi.

Rajnandini Shinde and Sandeep Parande

Rajnandini Shinde and Sandeep Parande

Parents complain that the school has only three teachers to teach all the classes. Although the zilla parishad school offers free mid-day meals under the government scheme, most parents do not want to send their children there because of these issues.

Dhanashree Gaikwad, a resident of Kalambe village, was initially sending her sons Paras, 5, and Mahi, 2, to Navjeevan Vidyalaya, but had to pull them out following a financial crisis. They now attend the zilla parishad-run Marathi school, but she is keen to send them back to Navjeevan when she can, as the difference in standard of education is quite stark. “I had seen a lot of improvement in Paras when he was at Navjeevan. “My son could earlier read the English alphabet from A to Z, and would even recite rhymes and count to 10. But at the zilla parishad school, he is not able to even read the Marathi alphabet properly and has forgotten the English alphabet, as the teachers and students only speak Marathi,” says Gaikwad, who is a Standard 12-pass and works on a farm, drawing R200 per day at best. “I want my children to be educated so they can get jobs and not have to be farmers like us,” she says.

But Sandeep Parande, a teacher at the Somardi school, argues there is no need for an English-medium school. “We have English in our curriculum already, so why do we need a separate English-medium school in the village, where many parents are either school dropouts or have done their own schooling in Marathi medium?” he questions.

Principal Ujwala Pawar adds, “We have 17 students at present from Standard 1 to 7. They get free education and free mid-day meals. The existing education system is good for students in these areas who cannot afford the fees of a private English-medium school.”

Nimbalkar, when asked if she provides mid-day meals for the students, says she cannot afford it. “Students carry their lunch box, and if some cannot afford to do so, we share our own tiffin with them.

Students who passed out from Navjeevan Vidyalaya say they don’t desire mid-day meals as much as a chance to continue studying in English medium till Standard 12. Alumna Rajnandini Mahendra Shinde, 18, is now a Standard 12 student at a junior college, but wishes she could have continued at Navjeevan. “I am grateful to have received quality education in my primary years. After Standard 4, I had to move to a Marathi-medium school run by a trust. Following that, I had no option but to enrol for a junior college which exists only on paper—there is no college building. Self-study is my only option for my HSC exam preparation,” says the teenager who dreams of becoming a pilot or engineer specialising in aeronautics or robotics.

“I am happy that Navjeevan Vidyalaya has got permission to start teaching Standards 5 to 12; it will help many students. Studying in an English-medium school will also give them more confidence to speak in the language, which doesn’t come from studying in a Marathi school,” she adds.

Like Shinde, Ankush More, a nine-year-old Standard 4 student at Navjeevan Vidyalaya is apprehensive about having to leave the school once he progresses to Standard 5. After school, he spends his time at his parents’ one-acre strawberry farm in Derewadi village. His father Chandrakant and mother Komal love having him around on the farm, but don’t want it to be his life. “We only want the best for our child. Farming does not pay well, so we admitted him in the English-medium school, hoping it would give him a brighter future,” says Komal.

As someone who completed a BCom degree in Marathi medium and then ended up working as a farm labourer, Sunita Paramane understands the importance of her son Sourya, 7, learning English for a stronger career prospects. “But with my husband earning a mere R150-200 per day, we were unable to pay the Standard 2 tuition fees at Navjeevan Vidyalaya. Despite that, the school management has not barred him from class. We are grateful to the school for allowing him to study,” say Sunita and her mother Taramati.

Rs 14 l

School’s average annual costs

Rs 3 l

School’s average annual fees revenue

Officials speak

S G Mujawar,

Education Officer (Primary Section), Satara district

“The school got consent for starting Standards 5 to 12, but for that they need to set up additional infrastructure, such as laboratories for science practicals. But 18 months have lapsed since the authorities granted permission. Now, they will have to submit their proposal to education department officials handling secondary to junior college levels.”

Prabhavati Kolekar, Education officer, Satara,

“As per our record, Navjeevan Vidyalaya is not registered as a secondary school… Usually, within 18 months of the sanction letter [for higher classes] being issued, the educational institution must adhere to the conditions, failing which the permission granted would automatically get cancelled.”

“On Navjeevan Vidyalaya’s chances of getting the education department’s nod again, yes, the educational institution will have to once again submit all the documents and follow the procedure. Once the committee sanctions the request, permission can be granted again. This entire process takes anywhere between six to eight months.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!