Amid public outrage over a 12-year age gap in a new romance novel, we ask: Should books be kept free of moral policing?

May-December romances are hardly new to books, but is at the centre of a controversy over Chetan Bhagat’s new novel, 12 Years: My Messed Up Romance. Representational pic/istock

He’S 33. She’s 21. He’s divorced. She’s never had a boyfriend… They shouldn’t be together. But they can’t stay apart.” Does this sound like romance or a red flag? It’s a question that has divided the Internet since author Chetan Bhagat announced his new book, 12 Years: My Messed up Love Story (HarperCollins India). Online, some have called the age-gap plot “creepy”, others have even termed it as “grooming”.

Bhagat tells Sunday mid-day, “The book hasn’t even been released yet. Nobody knows what the story actually is or how the age-gap issue has been treated. I think some people on the Internet might have been quick to jump to conclusions.” So why the moral outrage over Bhagat’s novel? Is it as Bhagat says, do people just love to hate him? Or are our ideas of “morality” and “moral policing” increasingly spilling over into our TBR (To Be Read) lists too?

Chetan Bhagat

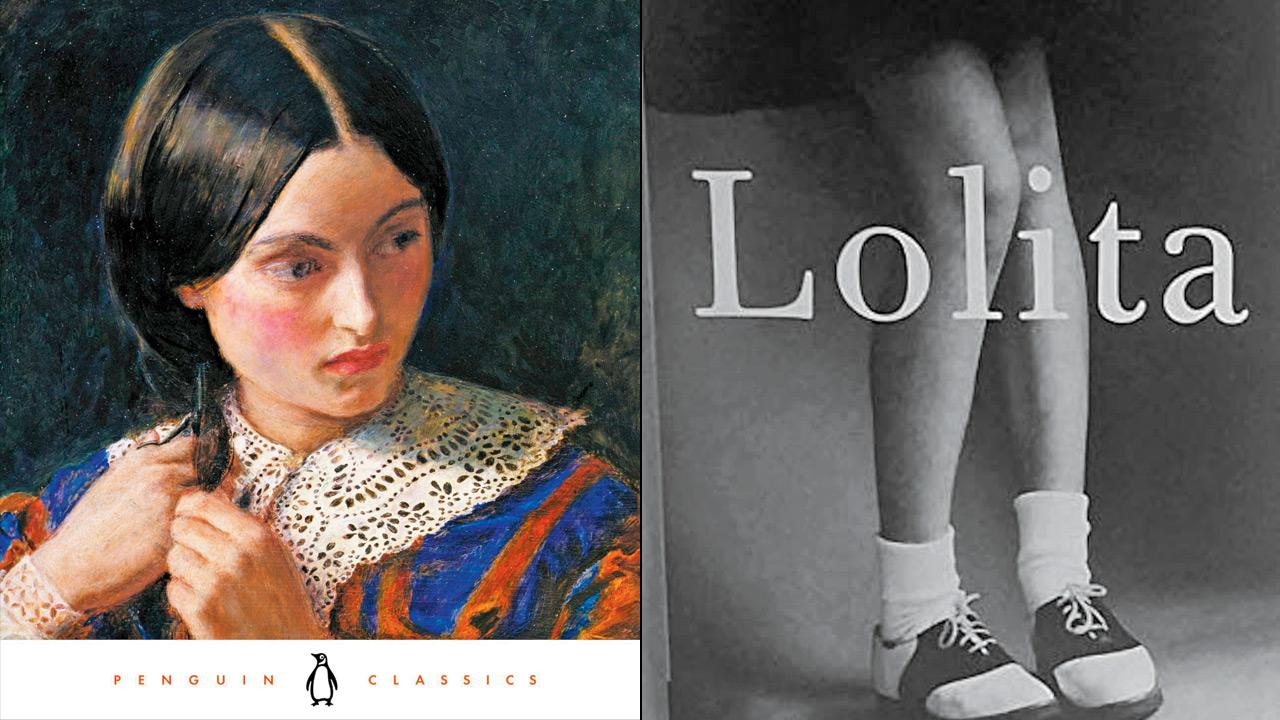

Literature, of course, is rife with May-December romances — relationships between a young person (May) and considerably older partner (December). The most notorious example is Lolita, a 1955 novel by Vladimir Nabokov, in which a professor abuses his 12-year-old stepdaughter. Despite the paedophilic plot, Lolita is now considered a classic. Even in classics written from the female gaze, the age gap persists. Take Jane Austen’s Emma, where the difference is quite similar to Bhagat’s new book, with Emma aged 21 and her love interest, Mr Knightley, aged 37. Or the far bigger gap in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, where Jane, 19, gets engaged to 40-year-old Mr Rochester.

But time and context matter, says Pia Oza, 19, a Literature student at St Xavier’s College. “A 10 or even 20-year age gap was normal when these books were written; things are different now. The more aware we become as a society, the more discerning we get, and this generation is quite critical of what we consume.” “Books like Lolita are considered classics because of the literary value,” she says, “On the other hand, Chetan Bhagat is seen as an unserious author. It all depends on how he’s written this book, of course.” It’s a challenge the author has stepped up to intentionally. “I wanted to write a story exploring a difficult conflict, like an age-gap romance — I wanted to see for myself if I could execute [it] well.”

It’d be unfair to make a snap judgment before we’ve had a chance to read the book, says Manisha Ghatage, associate professor at the Department of English, SNDT Women’s University. She offers the example of Love, Again, written in 1996 by Doris Lessing, telling the tale of a 65-year-old woman writer in love with a 28-year-old male actor. “At the time it came out, it was quite controversial. But it went on to be taught in colleges as feminist narrative,” she recalls, “It is a postmodern narrative about whether an ageing woman has the right to romantic longing, especially for a younger man. There’s a beauty and complexity in the writing that challenges readers, putting up a kind of resistance to what was considered the norm of the day.”

There have been several instances of moral outrage over books, some of which have even been banned due to risque content, or religious or political objections. But many of these same books — from Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, to Lajja by Taslima Nasrin, or even Riddles in Hinduism by BR Ambedkar — have also earned critical acclaim for broadening perspectives. “How a writer tackles the characters’ conflicts, their resolution, their chemistry, and whether they can reflect on deeper issues such as the dynamics that come with age, power and cultural stereotypes makes all the difference,” says Ghatage.

A file picture of a protest in Mumbai in 2004 against Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, which was banned in India and several other countries due to religious outrage. Pic/Getty Images

This is why Arundhati Roy’s God of Small Things, while featuring sexually explicit scenes — including incest — met with brief outrage, but went on to win the Booker Prize in 1997 for its nuanced depiction of the caste system and the associated “love laws” in Kerala. “Arundhati’s book may have been sexually explicit, but she was writing about deeper political issues. This may be why the right wing is making an issue out of her new book’s cover too,” says Oza.

Roy’s latest release, Mother Mary Comes To Me, a memoir centered on her complicated relationship with her mother, has come under fire for the unconventional choice to put a photograph of the author smoking on the cover, with some labelling her “ambassador of cigarettes”, and calling it immoral. And yet, the image is hardly new.

Classic like Jane Eyre and Lolita both featured wide age gaps between the protagonists. Lolita is now acknowledged to be paedophilic in nature, but is still read widely

“‘The cover features a photograph of Arundhati Roy by Carlo Buldrini, who, as readers will discover, is himself a character in the book,” says Manasi Subramaniam, vice president and editor in chief, Penguin Random House India. “The image has over the years become something of an iconic portrait of the author, widely circulated on the Internet. Its use here is entirely in keeping with the spirit of the work: intimate, unflinching and true to the life and story being told… We have included a disclaimer at the back of the book stating that we do not endorse smoking,” she adds.

Like any other medium of art, books — especially fiction — aren’t always meant to be taken literally. The problem is, they often are. Marathi erotica writer Sayali Kedar recalls the furore over her debut book, Desperate Husband, the bizarre reason behind it. “When I started, there was very little erotica from the female gaze, and nothing about a husband and wife’s relationship, especially in Marathi. For a country obsessed with marriage and making babies, why don’t we consider married sex erotic?” she questions.

Pia Oza and Sayali Kedar

She was prepared for the backlash from society over the risqué content, but what she didn’t anticipate was how “readers were imagining themselves in the story, but with the protagonist and not with their partners”. “I would get messages saying from men saying they found it weird to fantasise about the female protagonist because she is ‘someone else’s wife’. I had intended for readers to fantasise about them being with their partner in the story. But either way, it shouldn’t matter because these are fictional characters,” she says.

But there was also a flood of messages from those who did enjoy the book with an open mind. “I would get messages saying that my book helped them to open up to their partner. It encouraged me to keep going,” she recalls. And therein lies the problem with slapping morality on fiction — “Who decides what is acceptable and what isn’t?” Kedar questions, “Two people might look at the same story in completely different ways. One person might find it objectionable, another might find it illuminating. But never before have we had such easy access to authors and creators, so when we don’t like something it’s very easy to voice our objections on social media.”

And that’s great too, says Prof Ghatage. “Authors should have the liberty to create as they wish. Only with this creative licence can they question social issues and imagine a different world. And as readers, we should develop courage to read and think about these unconventional ideas — of course, you are free to agree or disagree too.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!