A new wave of Sindhi musicians are using music to preserve their language and reclaim their cultural identity

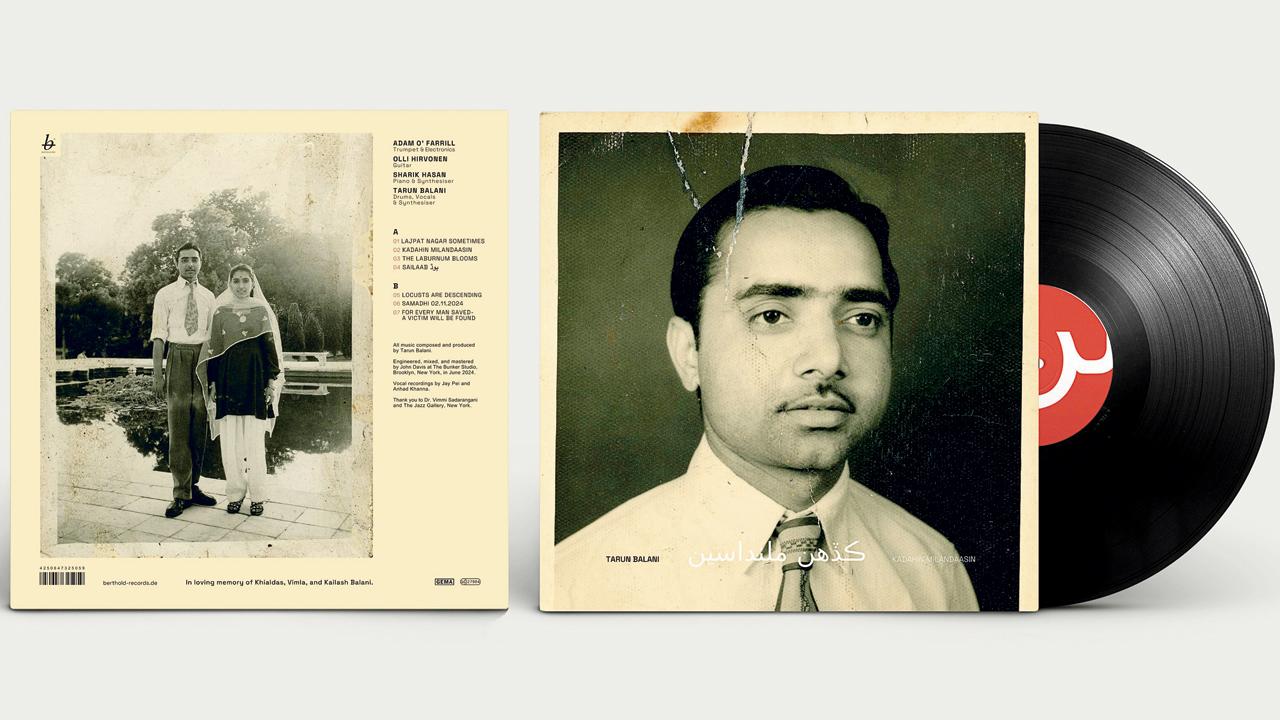

The cover art for Tarun Balani’s new album features his grandfather’s photograph and the album name, Kadhain Milandasi, in the Sindhi script. Pic/Mohit Kapil

Yov’ve probably heard Mast Qalandar in more ways than one, belted out at weddings, looped in remixes, or at a Sufi night. First written by Amir Khusrau in the 13th century, with verses adapted later in the 18th century, this qawwali has defined Sindhi music in the public imagination. Another tune, Ho Jamalo, was written as a celebration song in 1889 and continues to be remixed into several Bollywood numbers and renditions by Sindhi artists.

Sindhis, despite the turn of centuries, have clung to these songs. Post-partition, icons like Ram Panjwani and Master Chander gave the community many poems and ghazals, with Panjwani often playing the matka, commonly used as an instrument in Sindh. A host of other traditional Sindhi instruments did not manage to cross the border.

Andheri-based singer Vandana Nirankari says she began singing in Sindhi to preserve the language. Pic/Satej Shinde

Despite the community’s love for music, few originals have been produced after this period. Recently, a quiet shift has been occurring. A new wave of artistes are revisiting Sindhi identity through a more personal, contemporary lens and are using music to preserve language and also to reclaim their heritage.

Delhi-based jazz and electronic musician Tarun Balani’s latest album Kadhain Milandasi is rooted in memory, longing, and identity. The title is a poetic spin on Tadhain Milandasi (That’s when we will meet), a well-known verse from Tiri Pawanda, by iconic Sindhi poet Sheikh Ayaz, whose work was once popularly sung by folk legend Allan Faqeer.

Balani changes the phrase to ask instead: Kadhain Milandasi (When will we meet?). It’s both a question and a tribute to Sindh, the homeland he never visited, to Lajpat Nagar where he grew up among other Sindhis, and to the grandfather he never met. Predominantly instrumental, the album is a journey that makes the listener ask the question through the tracks. It’s only when you encounter the title track that Balani’s voice gently lingers in the background.

For Balani, the album is more personal “Because my grandfather KS Balani was a post-modern writer, photographer, and a painter,” he says. Balani grew up with his grandfather’s camera and photographs, even as his family refused to speak of their grief after he passed away at the age of 40 at the peak of his career. “It was only last year that I started to sort of investigate a little bit more about my own Sindhi identity,” says Balani of his quest which led to him creating the album. Its cover art features his grandfather’s photograph and the album’s name in the Sindhi script.

Eighth-generation Sindhi singer Jatin Udasi adds simple words from spoken Sindhi, and even a few English or Hindi words to his lyrics to attract a young audience

In a similar fashion, singer-songwriter Vandana Nirankari began singing in Sindhi to preserve the language. “You sing your ABCs, that’s why you have learnt it well. Without them being sung, we may not have remembered them well,” she says. With no training in singing, she initially began singing devotional songs and later shifted to creating music in more modern genres to hook youngsters. Her song Sik Mein, released in 2019, features a bit of rap and has garnered 50 lakh views on YouTube. It gave her the confidence she needed to continue on.

“When I started, there was a problem of audience. We had very little to no audience, and the people that we had, were above 35-40 years of age who preferred Sufi ghazals,” she says, adding that to attract a younger audience, she has taken iconic Sindhi numbers played during celebrations and weddings and created extended versions of them, either with a bit of rap, EDM, rock or pop. Her upcoming music will see afro house and synth. But youngsters still find it difficult to grasp. “After the virality of Paiso Aa, I think young Sindhis want to listen to Sindhi songs. But they want to listen to something new,” she adds.

Eighth-generation Sindhi singer Jatin Udasi opines the same. “Old kalaams [Sindhi poetry] are difficult to understand. It’s why, through a lot of my songs, I westernise the Sindhi boli. My audience also enjoys Bollywood covers translated into Sindhi,” he says. Udasi whose genre is mostly pop, has released originals like Sadke Wanya, wedding songs like Dhoom Machi Aa, and even taken a more devotional path with Lal Sain Beautiful. He adds simple words from spoken Sindhi, and even a few English or Hindi words to his lyrics to attract a young audience.

A deep dive into Sindhi music will usually reveal themes of longing, or you will find devotional songs, or those themed around a wedding. “Themes of loss and longing are so fitting for a community that lost everything; they are also strong themes in Sufi philosophy [which Sindhi music largely draws from],” explains writer, researcher, and oral historian Saaz Aggarwal.

There are some echoes of the traditional Sindhi music, poetry, and philosophy, especially that of 18-century Sindhi Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, that is reflected in today’s music.

“Bhittai’s words were sung to not just classical, but also folk music across Sindh. I have heard that ordinary people sang these words to simple tunes as they went about their work. This form is known as ‘Wai’, a kind of sung poetry where the power lies in the words, melody and spiritual emotions,” says Aggarwal, adding: “Shah’s philosophy entered the thoughts and minds of the people, it was such an integral part of life in Sindh that it has routinely surfaced in the interviews I have conducted.”

Bhittai’s Sur Sanrang — one of the 56 surs (or ragas) in the Shah Jo Risalo — which is associated with the monsoon season, had also inspired Balani’s music themed around climate change. Sindhi artists say there are many other challenges when it comes to creating originals. Nirankari says, “There is a lack of lyricists, music directors, and music producers. Aspiring musicians are going towards Hindi or Punjabi music because that market is made. So I think now we need artistes like us.”

Kumar Taurani, managing director at Tips Music, was instrumental in pushing Nirankari to create Sindhi originals and launch Tips Sindhi. “We have done it for the love of our language and our culture,” he says. And adds, “Sindhi artistes are now directly releasing music on YouTube because no one supports them. They get to perform only at events like the ones for Cheti Chand [Sindhi new year], nothing else.”

Taurani is of the opinion that Sindhi artistes need to be more committed to the cause. But he also thinks, “The fault is the community’s. Youngsters don’t speak or know the language and culture because parents have not taught them.” “So far it’s only been in Sindh that the language is alive and thriving, and young people continue to speak it even when they are quite westernised. This is not true [at present] in India,” says historian Aggarwal.

So why is the audience not in-tune with artistes or, as Nirankari says, is demanding originals only now? “It was looked down upon to speak Sindhi. I have come across people who have hidden that they are Sindhi. When people mock your culture, you tend to hide it,” says Jyoti Mulchandani, who blogs at Sindhi Khazana. Aggarwal adds, “Young people hesitate to identify themselves as Sindhis because of the shallow stereotypes — tasteless, money-minded.”

After the Partition, for Sindhis, survival was crucial. So, no one thought about luxuries like music. “Most Sindhi songs I listened to were because my father used to play them on the gramophone we owned. This is roughly 25-30 years after India’s independence. So, it shows that it took the community that much time to build themselves up, enough to have a disposable income that would allow luxuries like a gramophone,” says Mulchandani.

Aggarwal adds, “Most Sindhis in India don’t know about their cultural heritage. This loss is sharply distinct and poignant when you look at the content from social media influencers on either side of the border. In India, they speak mockingly of cultural stereotypes while in Sindh, the culture is precious and nurtured.”

In an attempt to shed stereotypes, Balani created a video for the title track of his album. “A lot of my family members are wearing the Sindhi topi, my mom is making koki. This shows how despite displacement, there’s a quiet resilience in how we’ve held on to our language and our culture,” he says.

So does Sindhi music have any future? Nirankari and Udasi believe it does, and their YouTube views are proof. Udasi adds, “The crowd in most shows, earlier, would include 40-45-year-olds and barely 350-400 people. Now, I see youngsters and I have sung in front of an audience that’s 10,000-strong. So there’s change.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!