It might have been a tool to breach administrative corridors for political expansion but for a veteran Urdu professor, who credits the Maratha ruler for compiling a one-of-a kind trilingual glossary, it has become a reservoir of socio-cultural cues from the past

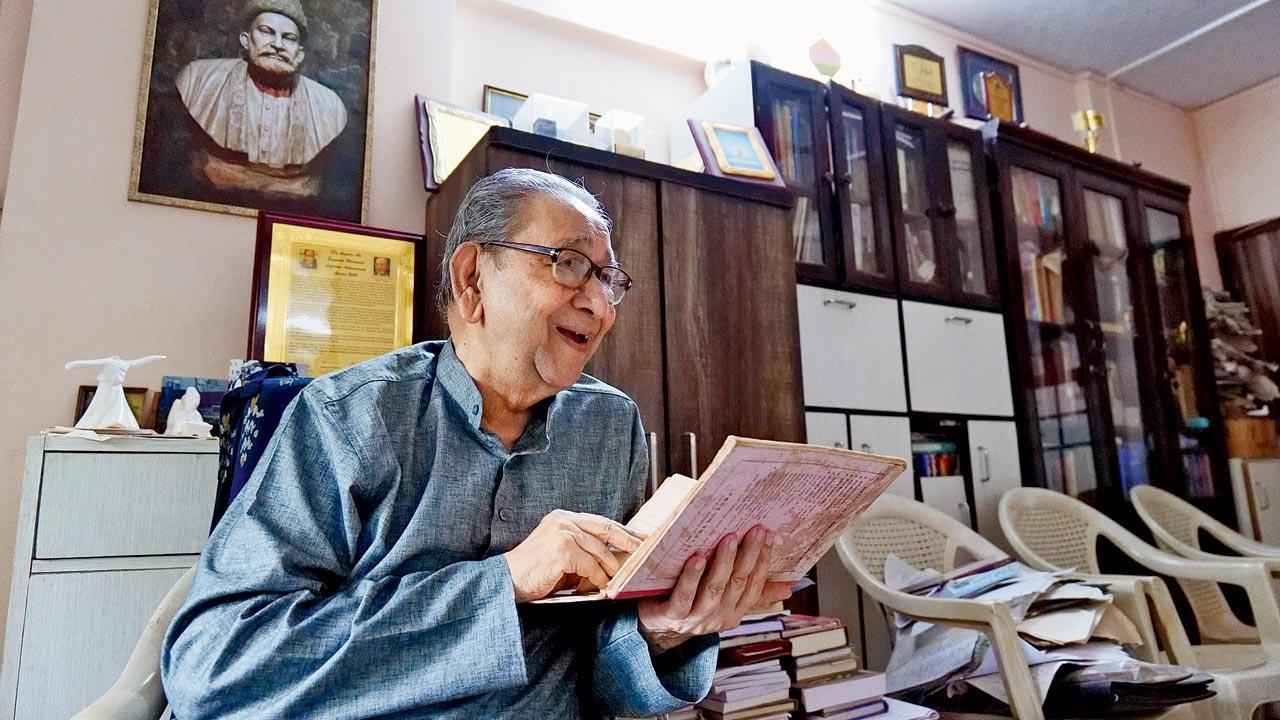

Professor Abdus Sattar Dalvi has had a five-decade long illustrious career in propogating Urdu. Pics/Shadab Khan

Professor Abdus Sattar Dalvi, 86, the founding head of the Urdu department at Mumbai University, was recently honoured with the Dr Asghar Ali Engineer Memorial Lifetime Achievement Award. At the felicitation held at the University, he discussed a unique 17th century linguistic effort that connects Maratha warrior Shivaji Bhosle with Urdu and Persian.

At his Bandra Reclamation residence, Dalvi shows us a book with brown damp edges. “This,” he says, his eyes dancing behind the spectacles, “is the first ever glossary of Urdu-Persian words compiled on Shivaji Maharaj’s instructions.”

It’s of particular interest to Dalvi give his five-decade long illustrious career in Urdu.

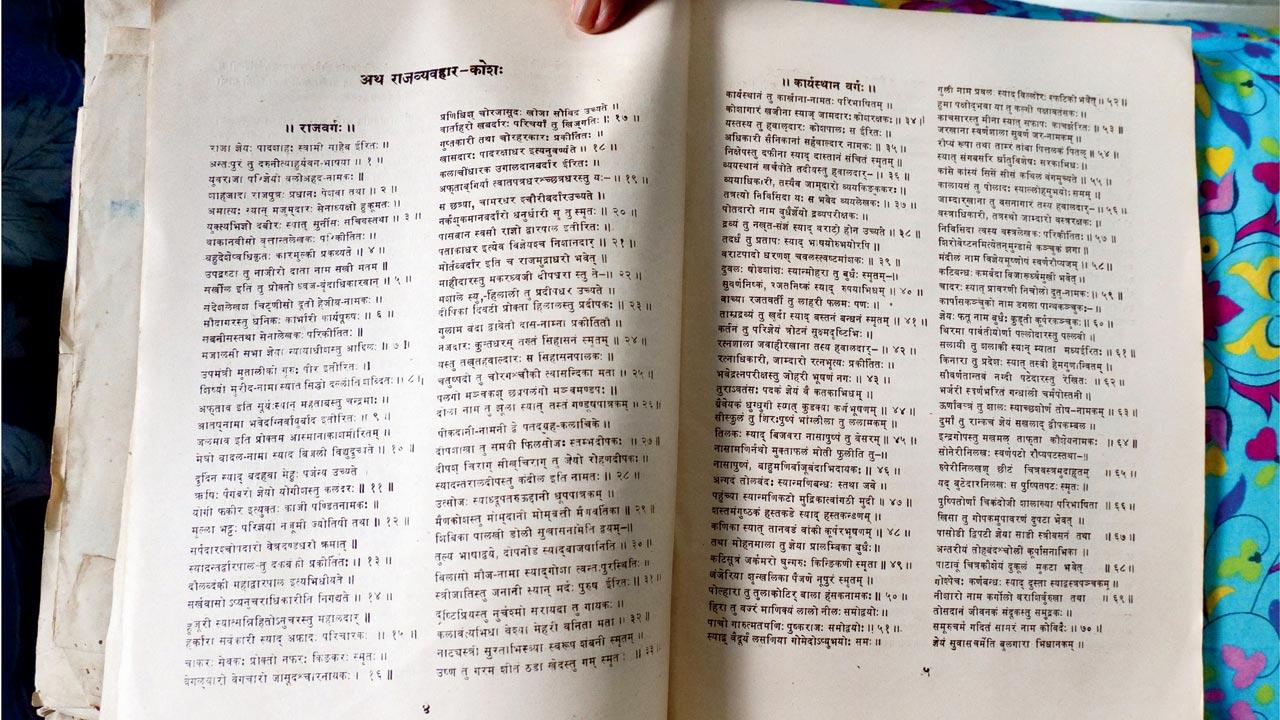

The glossary titled Rajyavyavhar Kosh contains administrative terminology, was put together between 1675 and 76. A special committee headed by scholar Raghunath Pandit undertook the task. “The official language for communication at the time was still Persian and the language of the common folk was Deccani Urdu, which was referred to as Hindustani,” he explains.

Dalvi owns a copy of the second print edition of Rajyavyavhar Kosh, the first ever glossary of Urdu-Persian words compiled on Shivaji Maharaj’s instruction in the 17th century

Dalvi owns a copy of the second print edition of Rajyavyavhar Kosh, the first ever glossary of Urdu-Persian words compiled on Shivaji Maharaj’s instruction in the 17th century

What makes the title unique is that it’s the earliest and first glossary of its kind in any Indian language. “Only after this was published did the tradition of printing dictionaries and glossaries in Indian languages take off,” Dalvi claims.

Other than being an academic work, it’s also a glimpse into the social fabric of the time. Dalvi thinks that had it not been for this glossary, the way of life of the people who occupied the Maratha region at the time, the language they spoke and how the courts functioned, would have been lost on us. “It has 10 chapters; each one touches a different aspect of life during Shivaji’s reign. Life in the court, the various regions in the estate, details about government departments, and hierarchical terminology that was in the army and navy, all find their way in here. Marathi versions of these Urdu-Persian terms have then been propagated.”

While some scholars believe that it was an effort at Sanskritisation, a way to replace Persian words, then common in state correspondence with Marathi terms, some see it as a way to gain access to policy information using language.

Incidentally, in the introduction to the glossary, the compilers have referred to Urdu and Persian as Yavani bhasha, or the language of Muslims, Yavans or foreigners.

While Dalvi owns a second edition copy, and a more recent version of it from 1976 edited by Dr Chidambar Kulkarni, who was then a reader at Mumbai University’s history department, the first edition was printed in Pune in 1802 and has been preserved at the Maharashtra State Archives. “The shabdkosh would have been in manuscript form prior to this,” he observes. A detailed study of the dictionary is on the octogenarian’s agenda, although he has already begun jotting down notes. “The word kitvi, which is a Deccani Urdu word for a small bird found near water bodies, finds a mention in the dictionary. Then there is nao and kashti meaning boat, jahaaz for ship, tokra for basket, kutubnuma for compass, sangtarash for stone carver, imarat for building. The document is rich with cultural cues of life as it was lived at the time, adding to its value,” he says.

Author Vaibhav Purandare in his just-released biography on the warrior king, says Shivaji’s attempt to imbibe Sanskrit officially began early. He even chose it as the language of his official seal. “This was a direct departure from the well-established norm of the Persianate Age: his father Shahaji, mother Jijabai and Shahaji’s agent Dadoji all had their seals in Persian, as did the other Hindu chieftains of the various Muslim kingdoms. Shivaji seemed to have made a conscious choice, and the language of the seal is the first unmistakable evidence of the Hindu element in Shivaji’s political philosophy,” Purandare writes.

Dalvi thinks it’s only natural that a ruler propagate that which is considered their ‘own’. “The Mughals did so with Persian and the Nizams of Hyderabad did it with Urdu. Naturally, the glossary and all other steps that Shivaji took were a means of expanding his power, and one of them was by establishing Marathi and Sanskrit as official languages.”

While the debate on whether he was a secular nationalist or Hindutva icon is ongoing, Dalvi believes he was certainly a broad-minded leader who did not believe in using religion to divide. “Several members of his army and navy were Muslims, including Siddhi Bilal and Siddhi Ibrahim. All rulers have the same thirst for expansion and power, and Shivaji was no different, but he was respectful of all his subjects,” he argues. Dalvi, who is credited with translating important Hindi, Marathi and English works into Urdu, including the classic Marathi poem Manache Shlok by saint poet Ramdas and saint poet Dnyaneshwar’s Pasayadan, is also the recipient of the Sahitya Akademi’s Translation Prize of 1990 for translating Ranangan by Vishram Bedekar.

Before we leave, Dalvi gets up to find the copy of Marathi Zabaan Par Farsi Ka Asar. It’s an 82-year-old title by Maulavi Abdul Haq. Dalvi recounts an anecdote about the correspondence between Shivaji and Aurangzeb in Persian. “In one of his letters to Aurangzeb, Shivaji had said that God does not show mercy only on Muslims, but on all humans. Khuda rehmatul-lil Muslimeen nahi balki Khuda rehmatul-lil aalameen hai, he wrote.” He adds that correspondence took place in Persian and Hindustani at Shivaji’s court which was also recorded by Venetian writer-traveller-physician Niccolao Manucci, who was brought in by Shah Jahan to care for his ailing son Dara Shukoh. Manucci mentions about his conversation with Shiavji in Persian and Hindustani, in his travelogue.

Deep roots

Dalvi explains how Marathi continues to be influenced by Persian and Deccani Urdu. The Marathi word akkal comes from the Arabic ‘aql’ (brain or intelligence). It’s a word that made its way to Persian and from there to Urdu and Marathi. Words like salla and tafsheelvaar have come from Arabic and Persian salah (advice) and tafseelvaar (detailed), he says.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!