With his next exhibition, artist Parag Tandel brings to a Colaba gallery the realities of life in a koliwada — an existence that is competing with the money market as well as the death of marine life

Migrants

Parag Tandel learnt to count with Bombay ducks. "My mother was in the business of selling dried fish at the local market here in Thane.

ADVERTISEMENT

Parag Tandel at his studio in Vitawa Koliwada.

She taught me to count with bunches of Bombay duck; each bunch would have a 100," says Tandel, 37. He shows us a set of six Bombay duck-like sculptures, cast in metal, each with the menacing gargoyle mouth that the fish is known for.

The Thane Creek shore where, in 2011, Tandel presented sculptures made out garbage fished from the creek. Pics/Sameer Markande

We are discussing fish and legacy at Tandel's studio, a small shuttered room in Vitawa Koliwada, near the shore of the Thane Creek. Tools and sculptures from when he was a student at MS University Baroda and Sir JJ School of Art are stacked in shelves. A tray of bleached fish bones — the spine of a large kotya (a croaker), to be specific — is placed on a table. "These bones are materials for a future project," he says, drawing our attention to his current works — three resin-cast shell-shaped forms, in vivid translucent hues.

Migrants

These and the set of Bombay ducks, which Tandel calls Memory, are part of his third solo show, which opens on August 11 at Tarq, Colaba. With this exhibition, titled Chronicle, Tandel has given aquatic shapes to his childhood memories and become a visual cataloguer of his fishing community and a life spent in Thane’s koliwadas.

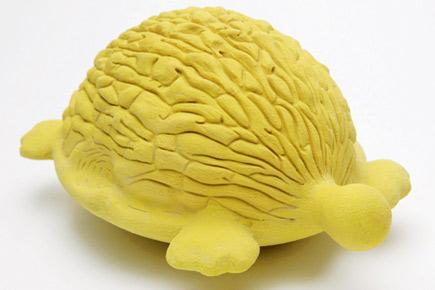

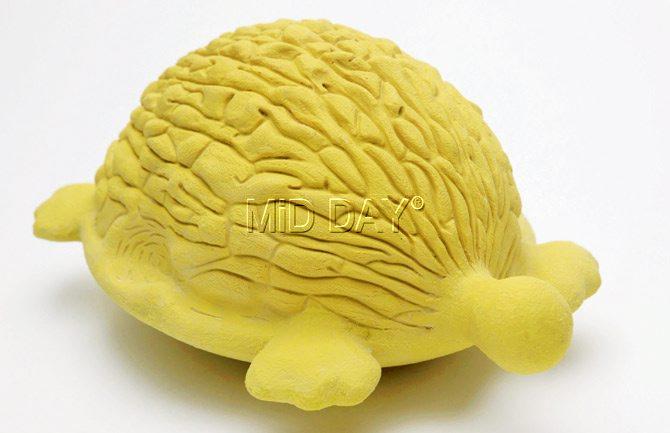

Extinct Form III

But it’s not just his childhood that Tandel is drawing inspiration from. "I grew up on narratives of my ancestors and what they had seen in this creek and at sea. These narratives are like fantasies to me and I have converted them into myths and stories. I am just chronicling these anecdotes," he says.

We ride to Chendani Bunder, on the opposite bank from Vitawa Koliwada and a short ride from Thane station. The rain plays tease; from the dense mangroves, the unmistakable whiff of cannabis wafts towards us. The port, once a premier hub for trading is now nothing but a little paved path leading to the creek. In its better days, it housed the Customs Department of the British Empire, to monitor boats en route to Gujarat and Karachi. For Tandel, it's more personal rather than political. "My parents tell me there was a time when 'eda masa' (Marathi for crazy fish) used to frequent these waters," he reminisces. What’s an ‘eda masa’? "Dolphins. They behave like crazed children, don’t they? And passing boats used to recount stories of whale sightings in the high seas," he explains.

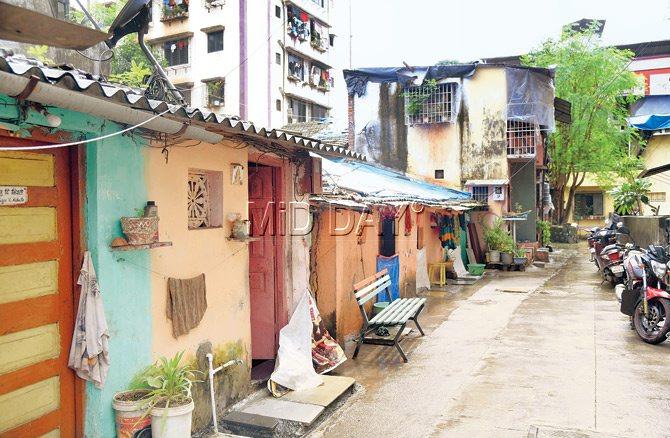

Tandel’s ancestral homes are in Chendani Koliwada, Thane, which has changed over time. Now, there is only one practising fisherman left in the village

Swimming in these waters in his childhood, Tandel has been aware of changes to his environment. In the past, on the banks of Vitawa Koliwada, he presented Big Catch under ArtOxygen’s Fluid City Project in 2011. Noticing how fishermen’s catch included a sizeable amount of garbage, he fished floating debris from the creek and turned them into sculptures. Most of his works in Chronicle are titled Extinct Form, and some of them, such as the ones back in his studio, are coloured in maroon, red and bottle green. "They may look beautiful but these are the colours of effluents found in waterbodies around the city," he says, bursting our bubble.

"I found sculpting a better approach than just putting up bottles of coloured water sourced from these places," he adds. "While all my works are rooted in these koliwadas and marine ecology, they are freestanding pieces. Memory may look like a Bombay duck, but that is my interpretation. I am just an image maker," he explains.

The sculptures, some protozoa-ish and others more recognisable as aquatic life forms, have a feminine quality to them — curvaceous and bulging. We quiz Tandel about this, and he shyly smiles and admits, "There is an erotic side to these sculptures. I feel the city is bulging, almost pregnant. Look at what happened to Thane in 2004 — it popped up! I keep thinking that Mumbai has mated with itself and it has produced hell." However, Tandel offers us a silver lining — that he finds the pregnant forms symbolic of the creative mind.

We are clearly now on what seems like a koliwada crawl, as Tandel guides us to his ancestral homes in Chendani gaothan. The air is spiked with the smell of fish frying in households and chicken potter around beside our feet. While some of the Mangalore-tiled houses remain, many a plot is full of construction activity for apartment buildings.

At the end of the street, through a gap between the row of houses, we can see the Central Railway’s trains pass by, a reminder that the Chendani Koliwada is part of railway history. The first passenger train in the country ran from Thane to Bombay, with Chendani Koliwada sitting close to its tracks. "It also meant that people from this koliwada left fishing in search

of jobs in the city, made accessible through the trains. With industrialisation and the development of CIDCO in Navi Mumbai, there were other job opportunities.

Men left for work from here in trucks to Navi Mumbai for work. It seemed a better routine than with fishing, where catches are unpredictable," says Tandel. Now, with only one fisherman left in Chendani koliwada, Tandel says that his community, which first came to Thane from Ratnagiri nearly five centuries ago, has been forever migrating. As homage to this migrant status, Tandel has made a fibreglass sculpture inspired by Olive Ridley turtles.

When we head to back to Vitawa Koliwada, we stand on the bank, watching trains pass by on the bridge above. Below, the creek flows silently, and lights up when the sun breaks out. "I think a kind of chaos has been created. There are these two worlds — the city and marine ecology — and chaos in between," says Parag.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!