Locked away from the world over the past couple of weeks,I have found solace in works of strange and sublime beauty

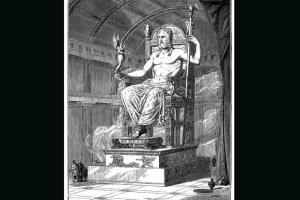

Fiona Benson's Zeus has no morals, stalking his victims, praising Presidents who live in shiny gold towers. Pic/ Getty Images

Poets possess keys to aspects of the world that are often hidden from our collective view. It is why I turn to them as often as I do whenever I find myself treading water, trying to make sense of things that make me question everything I think I have known. Like our global pandemic, for instance. Nothing prepared us for the weeks of forced isolation, the overwhelming insecurities that bubbled up from within, or the creeping doubt that nothing we really did for a living was of any actual significance. And so, I turned to poetry.

I began with Ilya Kaminsky, whose work I have spent many hours over, grateful for their existence and troubled by how they came into being. Kaminsky's latest collection, Deaf Republic — and only his second in 15 years — seemed to come from a place of startling familiarity, despite the poems being set in a fictional city called Vasenka. They seemed recognisable because of what they described: citizens who lived happily during a war. 'And when they bombed other people's houses,' he writes, 'we protested / but not enough, we opposed them but not / enough.' It moved and angered me, as he spoke of people living 'in the street of money in the city of money in the country of money, our great country of money…' because so much of it resonated with what we have been living through.

The impact of reading this while in isolation was powerful because Kaminsky lost his hearing at the age of four in Ukraine. He lived in silence until he turned 16 in America and was fitted with hearing aids. I thought about what he had once referred to as 'seeing in a language of images,' and what it meant for me, as a reader, to look at his world from that prism. As cities outside my window began shutting down, his poems set me free.

I was given access to another worldview by the English poet Fiona Benson and her (coincidental) second collection, Vertigo & Ghost.

This one was dark too, relying on Greek myth to somehow shine a light on the sexual violence that women have always had to contend with. Benson did this by portraying

the god Zeus as a sexual predator, a man 'who shoved a sawn-off shotgun / through the letterbox calling softly /like he was calling to the cat / that terrible croon, / SWEETHEART, / I'M HOME.' It was unsettling because it forced me to unlearn everything I thought I knew about a divine figure we had been trained to respect, a god of lightning and thunder who was married to goddesses and somehow given a pass to violate them.

Benson's Zeus has no morals, stalking his victims, praising Presidents who live in shiny gold towers, a flawed deity who would fit into India's current Parliament like a glove.

Another collection, an older one by American poet Claudia Rankine titled Citizen, forced me to look at the thorny subject of race, which, as any residential society's WhatsApp group can show, is alive and well in modern India. On the surface, Rankine's exploration of the covert and overt ways in which bigotry rears its head in America shouldn't find parallels in the country we call home. And yet, the minute we replace skin colour with caste, cracks start to appear in our carefully constructed façade of a tolerant, peaceful civilization.

What Rankine does is focus on microaggression — the thousands of minor, daily acts of prejudice, intentional or unintentional, that people of colour must grow accustomed to and accept as they go about the simple business of living. It compelled me to think of our own responses to the COVID-19 lockdown and the hypocrisy with which so many of us chose to vilify poor Indians whose only fault was walking home to meet a primal need for safety.

I recognise that the act of reading poetry is not only a private one, it is also one of privilege, given the implication that I need not worryabout shelter or where my next meal must come from. I believe it is important though because isolation creates an atmosphere of extreme scrutiny, allowing us to make changes to who we are and what we believe in.

No one doubts that the world emerging blinking into the daylight at the end of this pandemic will be a new one; all one can hope for is that the changes we must wakeup to will be for the better.

When he isn't ranting about all things Mumbai, Lindsay Pereira can be almost sweet. He tweets @lindsaypereira

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual's and don't represent those of the paper

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and a complete guide from food to things to do and events across Mumbai. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates.

Mid-Day is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@middayinfomedialtd) and stay updated with the latest news

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!