Despite skyscrapers and pac-man like development projects, the city is dotted with trees that would live on for centuries, if only we would let them; an environmentalist recaps myths and facts around 13 native varieties in a new book

A jackfruit at Veer Jeejamata Udayan in Byculla. Jackfruit trees can live up to 150 years. Pic/Atul Kamble

Just as we celebrate the birthdays of aging grandparents, we are not particularly cognizant of full-grown native trees in the neighbourhood, even the ones which have been around for centuries. Conservationist Roopali Parkhe-Deshingkar, 45, appeals for a collective healthy interest in indigenous trees which not just bear fruits and flowers, but also have a bearing on our social-emotional well-being; trees flourish in native literature and popular art; they conjure up rich imagery in local dialects. In her newly-released Marathi book Shatayushi (which translates to Centenarian, published by Saptahik Vivek, R175, 112 pages), Deshingkar celebrates 11 native (apart from two of African descent but adapted) long-living tree varieties which have blessed the Indian sub-continent with abundant gifts — from dermatological cures to firewood to flower beds to condiments to bio diesel.

Just as we celebrate the birthdays of aging grandparents, we are not particularly cognizant of full-grown native trees in the neighbourhood, even the ones which have been around for centuries. Conservationist Roopali Parkhe-Deshingkar, 45, appeals for a collective healthy interest in indigenous trees which not just bear fruits and flowers, but also have a bearing on our social-emotional well-being; trees flourish in native literature and popular art; they conjure up rich imagery in local dialects. In her newly-released Marathi book Shatayushi (which translates to Centenarian, published by Saptahik Vivek, R175, 112 pages), Deshingkar celebrates 11 native (apart from two of African descent but adapted) long-living tree varieties which have blessed the Indian sub-continent with abundant gifts — from dermatological cures to firewood to flower beds to condiments to bio diesel.

Shatayushi is a picturesque catalogue brought to life by nature photographer Dr Amita Kulkarni's breathtaking high resolution photos. It aids Deshingkar's environmental awareness efforts which stem from her personal interest in the wilderness and adventure sports. The Dombivali-born has been a national runner-athlete. In one of her mountaineering expeditions, around 25 years ago, she met noted Chipko movement leader Sundarlal Bahuguna and she decided to dedicate her energies to eco-friendly initiatives.

Similar chance meetings with two herpetologists, Neelamkumar Khaire and Dr Romulus Whitaker, turned her passion for snakes into a vocation. She now works closely with snake charmers, state Forest department and WWF Mumbai. Trained in conservation from the Wildlife Institute of India (Dehradun), Deshingkar is a resource person for many NGOs. The Thane-based wildlife blogger (popularly called Discovery Tai) has been at loggerheads with the Tree Authority and Thane municipality for saving a 500-year-old Baobab and a 100-plus Banyan. She has also been part of roadside mass plantation drives in Dombivli.

Author Roopali Deshingkar seen with the ancient Baobab in Thane. A Boabab promises a life of 500 years. Pic/Sameer Marakande

"Mumbaikars (and for that matter most city residents) are not attentive to the amazing growth cycles of their bountiful trees. Even the popular mango tree is not recognised in all its glory, leave aside Kadamb, Karanj and Moha," Deshingkar enumerates the 30-odd mango (Mangifera Indica) varieties, of which Alphonso is the most revered. The cash crop is usually not seen as a source of fire wood, although mango branches were used for the last rites in Kerala, she notes, adding that the departed soul is believed to attain faster salvation if cremated in the celebrated Amravruksha. She recommends greater attention to the juicy non-branded deep-forest mangoes, which enhance human bone density, and have been culturally under celebrated.

Shatayushi is written in a chatty style, so as to evoke wonderment about trees which are easily accessible, but not treated with the curiosity they deserve. Though these trees have religious associations (Banyan, Peepal and Audumbar are rooted in temple precincts), humans don't seem to treat them with any great care. Banyan (India's national tree — Ficus Bengalensis) leaves and branches are freely cut on Wad Poornima day, all in the name of an annual fast kept for a husband's long life; the Banyan's slightly hidden fruit is not even known to a city dweller's eye. Banayan fruits have come to the rescue of the drought-hit in the past in India, old gazettes mention. Similarly, Peepal (Ficus Religiosa) or the Bodhi Tree which has a place of pride in Hindu and Buddhist texts, also bears fruitlets. Peepal leaf has been a fine art symbol of rural life idyll. The Audumbar (Ficus Racemose) fruit, usually strewn all over the Dattaguru temples and called the poor man's fig, have been a staple diet for monkeys, deer and bears. In Maharashtra's tribal belt, the presence of an Audumbar tree in a prospective bridegroom's backyard is a solace to the girl's side. It is assumed that if the girl is abandoned by her in-laws in the night, the cluster fig (Umbar) will support her survival at the unearthly hour. Amusingly, Audumbar wood was traditionally used for the wooden threshold gradient at the entry of an old-style Indian house, and therefore it was associated with noble arrivals and good luck. The etymology of the Marathi word Umbartha tells a story of its own; it was remapped in popular imagination by the Smita Patil starring film.

Deshingkar feels Mumbai's Banyan and Peepal treasures near the Kanheri Caves constitute a great educational excursion for school going children, so do the other native trees in Mumbai's Raj Bhavan precinct, not to forget the old residents in Jeejamata Udyan. She feels young Mumbaikars should be taken on tree walks, more so after being made aware of literary, historical and mythological orientations of native trees. For instance, the Tamarind tree (Tamarindus Indica), an import from Africa, has a vital connect with revered Hindustani singer Tansen. The maestro's love for imli was so well-known that his fans planted lush tamarind around his grave in Gwalior. Equally interesting is the connection of Palm (Borassus Flabellifer) tree with indigenous Oriya and Tamil literature. Discoveries of dried Palm leaf manuscripts bring to life scriptures dating back to 3rd Century BCE. Bakul (Mimusops Elengi) or Spanish Cherry tree has been ever immortalised in poet Kalidas' delineation of Shakuntala. Culturally deep is Peepal's manifestation as a place of worship after Gautam Buddha attained enlightenment by sitting under it for seven weeks.

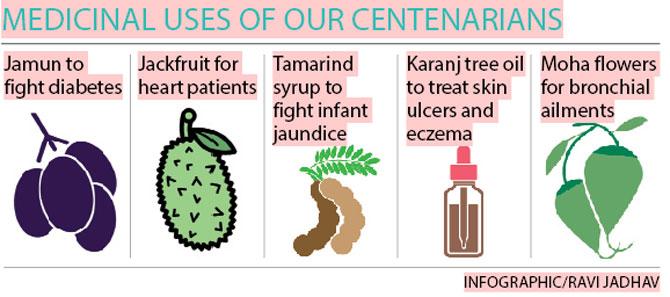

The centenarian trees touch our lives in more ways than we can gauge. Their medicinal uses are mindblowing — Jamun (Syzygium Cumini) controls diabetes and increases hemoglobin levels; the flavonoid and antioxidant content in Jackfruit (Artocarpus Heterophyllus) makes it an ideal nourishment for heart patients, apart from being a laxative; tamarind syrup is a quick button against infant jaundice; the nitrogen-fixing Karanj (Pongamia Pinnata) tree oil has antiseptic properties which are used to treat skin ulcers and eczema; the Moha (Madhuca Longifolia) flowers are not just alcohol generators but work against bronchial ailments. Shatayushi recapitulates the use, applications, and significance of the trees in a layman context; it presents tree truths which are already researched-documented but yet missed out on. In a city which is fast losing its Baobabs, Peepals, Banyans and Mangoes due to underground metro construction and other urban conveniences, it is good to be gently reminded of the rich green 'tree-full' lives we can live and let live.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@gmail.com

Catch up on all the latest Crime, National, International and Hatke news here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!