Translation, more visibly than other practices dispels the cult of the solitary genius, as it foregrounds the inherently collaborative nature of art

Illustration/Uday Mohite

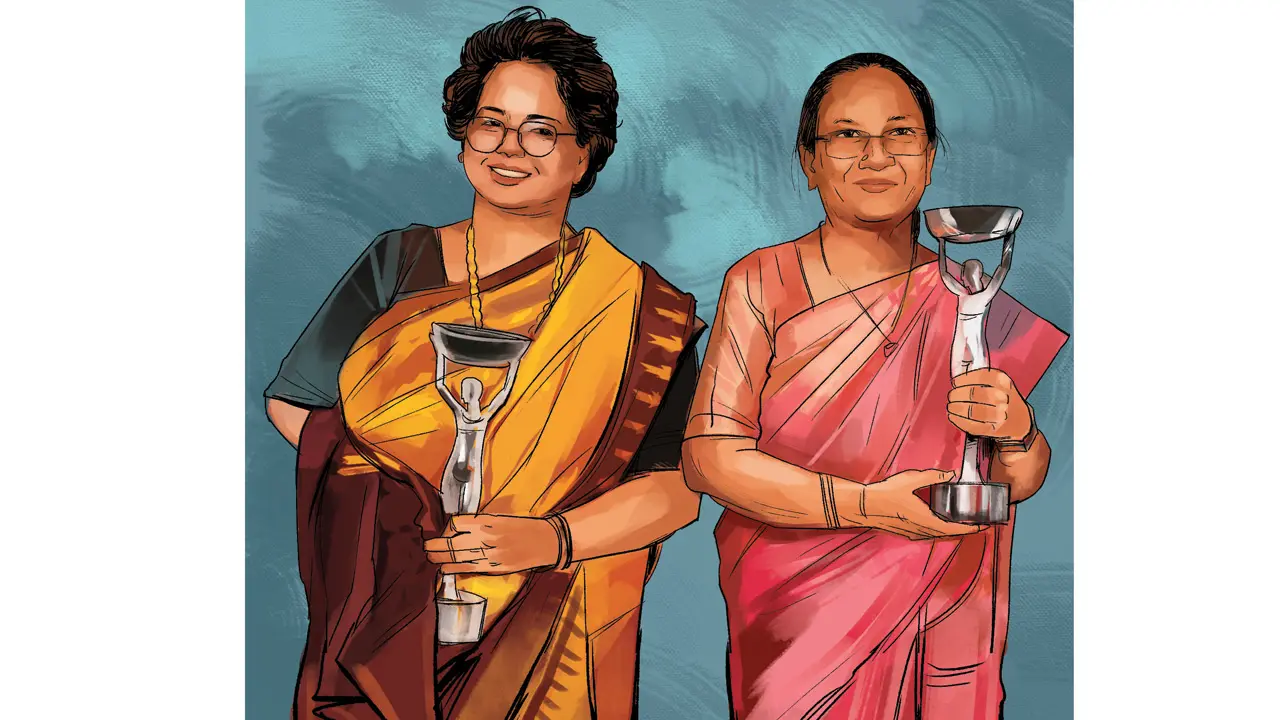

![]() Now, when schadenfreude is the commonest mode of wishful thinking — yaniki, our yearnings are dedicated to the failures of others more than the realisation of our own dreams — watching Banu Mushtaq and Deep Bhasthi hug as they won the International Booker was an island of sweet emotion. It was a saturated embrace of worlds, Kannada and English, Muslim and Hindu, city and town, curly hair and long hair, an older woman and a younger one, the story-writer and the writer-translator, a gold-pink silk tissue and a mustardy gold temple sari, two different forms of excellence and a same-same love for language. Maza aa gaya.

Now, when schadenfreude is the commonest mode of wishful thinking — yaniki, our yearnings are dedicated to the failures of others more than the realisation of our own dreams — watching Banu Mushtaq and Deep Bhasthi hug as they won the International Booker was an island of sweet emotion. It was a saturated embrace of worlds, Kannada and English, Muslim and Hindu, city and town, curly hair and long hair, an older woman and a younger one, the story-writer and the writer-translator, a gold-pink silk tissue and a mustardy gold temple sari, two different forms of excellence and a same-same love for language. Maza aa gaya.

“This moment feels like a thousand fireflies lighting up a single sky — brief, brilliant, and utterly collective,” said Mushtaq in her speech, offering an image where we might each shine alongside others, a moment out of the cinematic poetry of popular films. In contrast, Bhasthi made us smile when she said, “I did not want to jinx our chances by writing a speech”, but she had “dared to make some notes titled just in case” on her phone.

Translation, more visibly than other practices dispels the cult of the solitary genius, as it foregrounds the inherently collaborative nature of art. I do not mean collaboration in a material sense, but in a spiritual sense — where all art is created in tandem with the worlds embedded in language. The translation of a work is about mutual listening and speaking not literally, but across languages and works and sensibilities. Across its bridges of togetherness and spans of solitude we work and work and make and make a thing which is both individual and collective at the same time.

In an earlier interview, Bhasthi talked of immersing herself in the larger cultural world Mushtaq’s stories emerge from — watching Pakistani dramas, listening to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and reading Andaleeb Wajid’s novels — in order to render the translation “with an accent”, to help it feel organic.

Art can be an act of love, born from a deep attention to the world and the contemplation of others. As Mushtaq put it “In a world that often tries to divide us, literature remains one of the last sacred spaces where we can live inside each other’s minds even if only for a few pages.”

“From people, people, people — people with no love for one another, no mutual trust, no harmony, no smiles of recognition even — I had desperately wanted to be free” starts the first story in Heart Lamp, describing life in a city. Reading it brought to mind the cacophony of Indian Cannes costumes that darted like “screeching crows” at our screens, more acts of ego, which can be a trap, than glamour which after all is one kind of liberty. To lose oneself in other realities has become so impossible for those who make our mainstream culture, that they can no longer conjure up a competent fantasy (yes, The Royals I’m looking at you), to light up our dark, like a thousand jugnus, like heart-lamps.

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at paromita.vohra@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!