As quick-commerce apps speed up consumption, consumers are slowing down, reclaiming control and common sense by returning to local markets

Karen Dourado shopping at the local market near Orlem Church, Malad. Pics/Nimesh Dave

A few weeks ago, Entrepreneur Binny Varghese deleted all his Quick-commerce (Q-commerce)apps. Since it’s a small office and they work with food and raw materials, they used to order a lot on these platforms, as it is challenging. It helped that everything came with an invoice, so accounting is easier. At home, both he and his wife, a working couple, have limited time in the evening or morning. “So when our cook arrives, we would essentially just panic cause we don’t have any veggies in the fridge, so we would simply BLINK our eyes to get IT, and slowly the ease turned into a habit — a very expensive, and lethargically contagious habit.”

Varghese feels, “It’s a great service to have at your fingertips, especially for an emergency but then you only see and buy what you see, and then slowly you buy only what the app nudges you to buy, and then you are restricted with what you see in that window in your palm and you forget the possibility of the actual Window Shopping at the hypermarket or even the local market/bazaar.”

Pic/iStock

Pic/iStock

He realised it wasn’t helping — and might even be doing the opposite. “Your choices are limited to what the app shows you. You can’t touch, feel, or smell anything — let alone negotiate. And for me, food and cooking are romantic. I want to pick up a piece of fruit, smell it, and feel its ripeness. If possible, taste it — like grapes, for example.

It’s usually cheaper to buy directly, and in most cases, the produce is fresher too. Plus, your body moves — you don’t end up feeling sluggish. Honestly, it’s also just nice to step out with my wife and explore the markets together, whether it’s the local vegetable mandi or a big supermarket.

At the fruit market

At the fruit market

It’s a bit like getting off a dating app and trying to meet someone in real life. It takes effort, it may or may not work; but at least you tried. And there’s no regret in that.”

A fee for everything

Malad-based photographer Karen Dourado was initially thrilled by the convenience. “You could buy anything from a pin to a piano,” she says. During outdoor shoots, the app was a lifesaver for last-minute props or snacks (egg patties were her go-to).

But the thrill faded fast. “Once I got hooked, they started overcharging. There’s a fee for everything — handling, surge, rain — and a bunch of hidden charges. The listed prices don’t include GST, so your cart total increases accordingly. What feels like a '30 saving turns into '50 extra at checkout. You feel completely duped.”

At the fish market

At the fish market

Worth the wait?

For many consumers, the promise of 10-minute delivery — the core appeal of Q-commerce — no longer holds. Orders now routinely take 25 to 30 minutes, often matching the timeline of local kirana deliveries, but with added delivery and handling fees that the neighbourhood store doesn’t charge.

“Premium services on these apps once delivered real value — lower prices, faster delivery, tangible perks. But now, even subscribers face extra charges, making ‘free delivery’ feel like a myth. The benefits are diluted, and what remains is a growing sense of being short-changed,” says Dourado.

Quality dip

Most consumers will agree that the quality of fruits and vegetables used to be very good. That was part of their promise, but lately, that claim no longer holds. “For the price you’re paying — and often paying extra — you’d at least expect consistent quality. I’ve even been willing to spend more for things like eggs, assuming I’d get better produce, but that hasn’t been the case any more. Twice, I have found eggs in premium quality eggs,” says the Bandra resident.

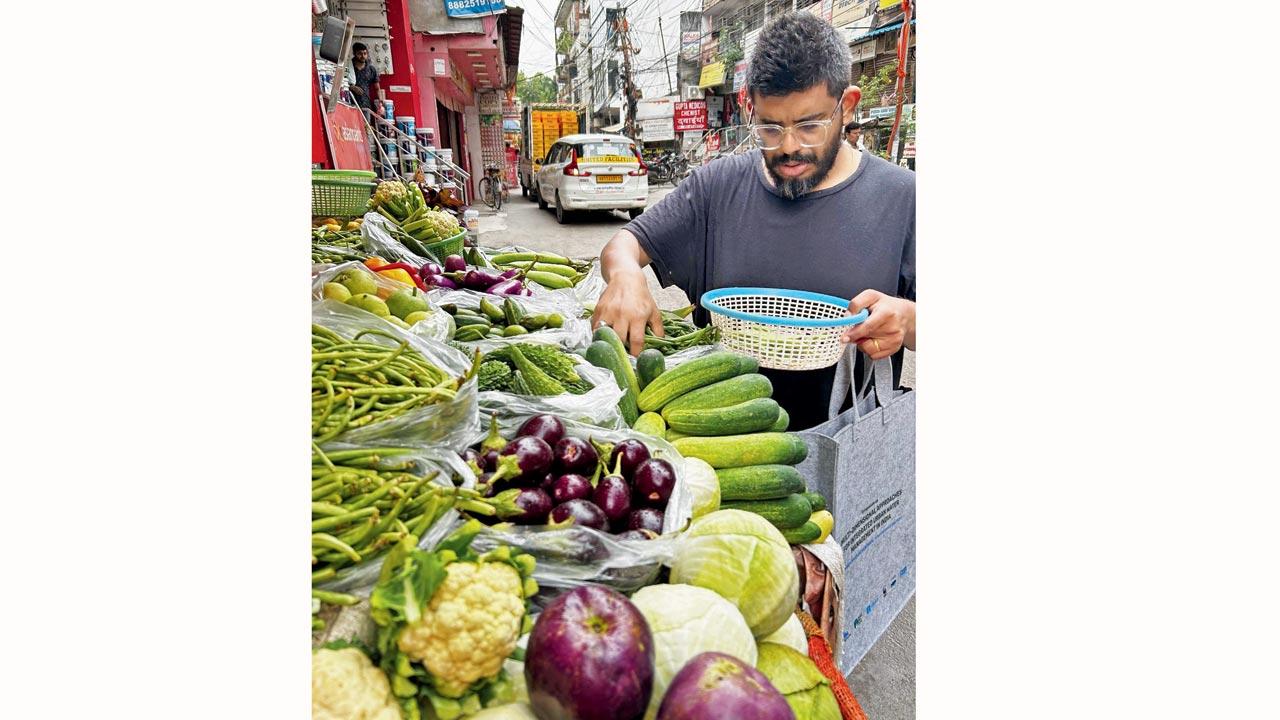

Binny Varghese

Binny Varghese

Point of no return

Dourado points out another recurring issue: “Most Q-commerce platforms have a strict no-return policy for groceries and essentials. Unlike fashion or electronics, if something arrives damaged, expired, or just not what you expected, you’re usually stuck with it. It leads to waste — and a lot of frustration.”

A Bandra resident echoes the sentiment. “They used to be very responsive. If something was wrong, you’d get a refund — no drama. However, the process is now complicated. You’re required to upload photos — within limits — and if more than one item is bad, you need to raise separate complaints.

Ruchika Ahuja at the grocery store near Chandivali.

Ruchika Ahuja at the grocery store near Chandivali.

Once, I received melted ice cream. The platform insisted I was wrong before finally sending someone to collect it. Another platform did something similar — refused to resolve an issue until the item was picked up. It’s tiring.”

Despite the glitches, she admits the convenience still has its place. “I haven’t stopped using these apps completely. But I’m back to my local kirana for most things, and I’ve started using Amazon Fresh — it arrives the next day, with no hidden fees. In fact, prices on Q-commerce platforms can be '100–'150 higher for the same item.”

She adds, “Returning to my neighbourhood store feels smarter. It may not be perfect, but it works — for now.”

Ketan Bhanushali and Hardik Gori

Ketan Bhanushali and Hardik Gori

Fast and frivolous

Dourado points out that she often ends up buying things she doesn’t need, to meet the minimum order value for free delivery. “You’re trying to avoid a '30–'50 fee, but you end up spending more and cluttering your kitchen with extras,” she says. Another gripe is the excessive plastic packaging, especially with fruits and vegetables. “What’s the point of convenience if it comes wrapped in layers of waste?” she asks. For those trying to shop sustainably, Q-commerce often defeats the purpose.

Oversharing, much?

Varghese is aware that quick commerce apps collect large amounts of personal data, including your phone number, location, browsing history, and purchasing habits. “This data may be shared with third parties for advertising, stored insecurely, or used to manipulate purchasing behaviour. Many users are unaware of how much they’re giving away just by ordering a snack,” he adds.

The hidden cost

Chandivali-based real estate agent Ruchika Ahuja feels that the average urban consumer has become increasingly dependent on instant delivery. Groceries, which were once bought monthly, are now ordered on demand via online platforms. “We’re happy to pay more for the convenience — whether it’s late-night cravings, stationery, electronics, or even clothes. The idea of stepping out in the heat or traffic feels unnecessary. Everything comes to us fast. But this convenience comes at a cost. I’ve started to realise that my ability to plan, adjust, and manage money is slipping. Instant availability has made us less patient, less resourceful, and less intentional with how we use our time and money. I used to walk to my local grocery or kirana shop. It wasn’t just about the purchase—it was a habit, a social connection, and sometimes even a smarter deal. I could check the freshness of vegetables, ask for recommendations, and often get better prices. Visiting often built a bond with the shopkeeper, and that familiarity came with trust and reliability. And importantly, there were no hidden delivery fees, surge pricing, or handling charges. Q-commerce is great for emergencies. But for everyday essentials, I’ve started choosing local shops again. Supporting small businesses fuels the local economy and keeps our community vibrant. It also keeps us active, engaged, and mindful. Let’s not let convenience make us lazy. A little effort goes a long way,” says Ahuja.

Go local for vocal

Q-commerce may be fast, but it’s slowly killing the heart of retail. Ketan Bhanushali, proprietor of Kohinoor Super Market in Kurla, has been operating his grocery store for years, but says the rise of Q-commerce platforms has severely impacted his business.

“In the last two years alone, we’ve seen a nearly 50 per cent drop in sales. Q-Commerce offer deep discounts and below-cost pricing tactics that we cannot match. It’s not just competition, it’s disruption,” he says.

Bhanushali points to what he calls predatory pricing and anti-competitive practices, accusing platforms of favouring select sellers, launching exclusive products, and using discounts to lure customers away from local stores.

“These apps have fundamentally changed how people shop for essentials. But the model feels skewed — retailers like us operate on thin margins, and we can’t afford to lose more customers to unsustainable pricing games.”

He adds that quick delivery may be convenient, but it’s also dismantling the traditional retail supply chain. “We’re forced to adapt without the deep pockets or tech support these platforms enjoy. The Competition Act of 2002 was designed to ensure fair play — yet many of these practices seem to skirt those principles.”

For Bhanushali, the concern is not just about revenue — it’s about the long-term survival of traditional retail. “Q-commerce isn’t going anywhere. But unless there’s a level playing field, neighbourhood stores like mine may be pushed out altogether.”

Live and let live

Hardik Gori, who has been running Siddhivinayak Wholesale Mart (Low Price) in Mulund for the past nine years, says his business has been impacted by online delivery apps, but he continues to thrive — thanks to loyal customers and the consistent quality of goods he offers.

“Earlier, people came to the store, interacted, and we built relationships. Now, with online delivery, convenience has replaced connection,” he says.

Gori believes Q-commerce has made customers lazy and less loyal. “We also offer free home delivery — and more. We know our customers by name, suggest new products based on their needs, and ensure quality. These platforms push discounts and notifications, but they don’t know the customer. Their warehouses aren’t clean, quality is inconsistent, and prices fluctuate unfairly between users.”

During the COVID-19 lockdown, Gori’s store continued to deliver essentials, even to quarantined families, without shutting its doors. “We risked our lives to serve the community. These apps weren’t around then.”

He also highlights the everyday realities of running a small retail business, including rent, salaries, taxes, electricity, and the staff’s livelihoods. “This isn’t a side hustle or a funded startup. This is our only source of income, and we work 14 hours a day to make it work.”

For Gori, it’s not about fighting tech — it’s about fair competition. “We’re not against innovation, but customers shouldn’t forget that local retailers are part of the same community they live in.”

50%

drop in sales for retailers as quick commerce platforms offer deep discounts

Fresher produce

What you see is what you get —produce is fresher than app-based alternatives, having skipped long transit or mishandling.

Supports local

Buying seasonal, local produce gives a meaningful boost to nearby growers and fisherfolk.

Less waste, more sustainability

No plastic overload or unnecessary packag-ing. Taking your own bag and dabba like most do at City light Market in Dadar can reduce your environmental footprint.

Buy only what you need

Need one tomato or a sprig of mint? That’s all you’ll get. No forced minimums, no accidental pantry clutter.

Real human connection

Over time, your vendor knows what you like, shares what’s fresh, offers helpful swaps, recipes and even extends credit. It’s trust you can’t tap into with an app.

Varghese’s Old-School Shopping Survival Guide

Delete the app.

There is no other way.

Make a “to-buy” list.

Post it on the fridge or share a family note. Add to it throughout the week instead of making impulse purchases from your cart.

Turn shopping into an outing.

Not a chore — a mini ritual. Hit the supermarket with a playlist or a partner, stock up in bulk, maybe grab a coffee after. Romantic, no?

Know your neighbourhood.

Find the kirana near you that stocks your daily must-haves. Add it to your evening walk or post-work pit stop.

Visit the big bazaars occasionally

. Wander, discover something new, and maybe haggle for the fun of it.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!