The Mumbra railway mishap that claimed four lives has sparked a slew of railway reforms that will come into effect early next year. In the meanwhile, we ask seasoned travellers in the city tricks and tips they have figured out for a safer commute

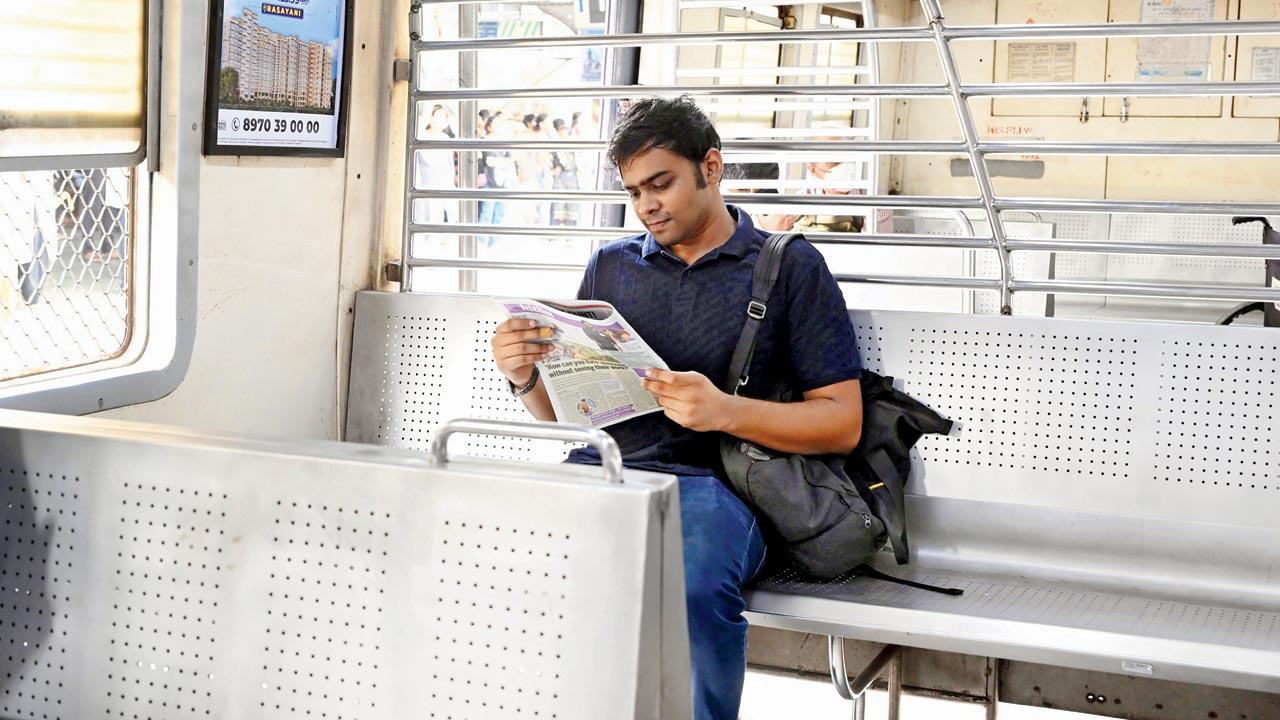

File pic

Nearly a week after the Mumbra mishap, when four people died and nine were injured after falling off two overcrowded trains as they crossed each other, a five-member committee continues to deliberate on what exactly went wrong that day.

Conflicting theories abound, ranging from witnesses saying they felt they were hit by something, to someone saying that one commuter’s nausea triggered a chain reaction among passengers, to impact dents on the coaches leading to a new theory that an alien metal object hit the train.

It may be a while yet before the experts figure out how to prevent a repeat of the incident. Meanwhile, Mumbaikars continue to risk their lives on their daily commute to and from work. Sunday mid-day speaks to some commuters who have figured out their own cheat code to travelling safely in the city.

1 Early bird gets the worm

Rutuja Balraj, 21

Route: Kalyan-CSMT

Media graduate

Using trains since: Six years

Rutuja Balraj’s biggest fear is missing her Kalyan stop and having to wait at stations beyond her stop, most being remote and lonely. Pics/Shadab Khan

Rutuja Balraj’s biggest fear is missing her Kalyan stop and having to wait at stations beyond her stop, most being remote and lonely. Pics/Shadab Khan

Every day, Rutuja Balraj would leave her home in Kalyan at 5.40 am, armed with a packed bag and mental grit. To make it to her 8 am lectures at St Xavier’s College, Fort, she had to catch the 6 am slow local: one of the few trains she could reliably board without being shoved aside by the crowd. For four years, she made this journey which was a two-hour ride each way, navigating the city’s Central line chaos with near-military precision.

“Fast trains come from beyond Kalyan, and they’re impossible to board. I only stick to slow, Kalyan-starting trains,” says the 21-year-old. “If I miss my regular, I take an AC train. It’s more crowded later in the morning.”

Rutuja Balraj

Balraj’s voice is calm but practised, like someone who has built muscle memory around every push, pause, and platform. If a train looks too crowded, she skips it. “In 1995, my mom fell off a crowded train and was left with a severe knee injury. Since then, I’d rather be late that risk a packed train,” she shares.

Her biggest fear is missing her stop. “Getting down at Kalyan is a game. You have to strategically get up from the seat two or three stations early. If you miss that window, you’re stuck till Ambivli or some remote station beyond. I’ve had to wait alone at near-empty platforms for 20 minutes before the next train to CSMT comes along.”

Her challenges multiply when she’s carrying a laptop or camera. “You need to position yourself perfectly. It’s chaos with 10 people getting off and another 20 getting on. I’ve seen people fall.” She casually remarks that she’s seen people pass out from suffocation on crowded trains all too often.

“Only the privileged can afford safety. First-class, AC compartments — they buy you space and time. Others just have to survive.”

Having recently graduated from the BMM programme at St Xavier’s, Balraj looks back on her commute with a mix of awe and fatigue — a daily race that shaped her not just as a student, but as a Mumbaikar.

2 First station, first serve

Ashish Dwivedi, 32

Route: Virar-Andheri

Publicist at a financial services company

Using trains since: 18 years

Travelling on local trains since he was 14, Ashish Dwivedi, now 32, is no stranger to the tricks of the Mumbai commute. Until 2019, three hours of his day went towards the commute between his Naigaon home and Andheri workplace. The tedious journey prompted him to move — not closer to his office, but farther away. He moved to Virar, which now means he spends an additional 20 minutes on the train. And yet, it’s made his commute easier.

How? Virar is the starting station, which means Dwivedi has a chance at finding a seat, or at least a safe spot to stand inside the coach. The problem at Naigaon, which comes a few stations later, was “no space”. The proliferation of so-called “train gangs” adds to the problem. “They don’t let other people come inside because it hampers their comfort,” he says. Many travellers stand on the footboards, putting their lives at stake to get home as quickly as possible. “They board the train regardless of how crowded it is; they just want to get home quicker,” he adds.

Recounting his own narrow escape from 2017, Dwivedi says, “I boarded the train from Naigaon somehow, but while hanging on the footboard, there was so much pressure from the crowd that my hands went numb and I nearly lost my grip, almost falling into the creek between Naigaon and Bhayandar, but somehow managed to stay on the footboard long enough, till it reached Bhayandar station, and then sat on a bench to process what had just happened. I could have fallen off that day. I took leave from work that day, went home and bought a motorcycle on loan just to avoid trains.”

After this life-altering event, Dwivedi also began investing in life insurance and SIPs, creating a safety net for his family.

The same year, he suffered an injury to his lower back when he resumed train travel during the monsoon. The injury, sustained when he was shoved by rushing passengers, rendered his body temporarily immobile.

He moved to Virar in 2019. “I can get inside the train comfortably,” he says. But, it’s still tedious. “I have to leave early to make it for the train by 7.30 am. So, I have no personal time.”

To disconnect from the routine pressures of his office commute, Dwivedi carves out time to relax at the beach every other night. He believes that self-care is essential.

3 Target the coaches at the far end

Pratham Mrabhakar, 20

Route: Mulund-CSMT

Brand strategy intern

Using trains since: Six years

Pratham Mrabhakar is full of train travel hacks. Pics/Ashish Raje

Pratham Mrabhakar is full of train travel hacks. Pics/Ashish Raje

If there's a science to surviving Mumbai locals, Pratham Mrabhakar has perfected it. A regular commuter from Mulund to CSMT, the 20-year-old has spent the past six years experimenting with compartments, routes, and timings — all to avoid the city’s infamous train rush. His cheat code begins with targeting coaches at the far ends of the platform. “The front and rear compartments are emptier because the staircases are always in the middle,” he explains, “People don’t want to walk those extra two minutes. But I do. That’s where you get space.”

The second class coaches near the compartments for women or persons with disabilities are “more crowded because they’re closest to the stairs”. He also aims for the middle doors of long compartments, not the sides. “Everyone comes from both ends and flocks to those. The middle is the sweet spot.” His techniques for avoiding crush hour does not end there. Mrabhakar sometimes chooses the compartment based on where he needs to alight at his destination station. “If I have to alight quickly at CSMT, I board the part of the train closest to the exit gates. That can save five minutes.”

In his early commuting days, Mrabhakar experimented with AC trains, but no longer finds them worth the money or effort. “There was a 6.55 am AC fast from Dombivli that I’d catch from Thane. For a while, it was great! It was early, reliable, cool, and I’d get a seat.” But that changed quickly. “Now, queues begin 10 minutes in advance, like the Metro. If you’re not early, you can’t get on it.” He also swears by M-indicator and clever hacks, like buying a cheap hook to hang his laptop bag from overhead rods to relieve shoulder pressure.

There’s a reason Mrabhakar applies cold logic to every aspect of his commute; behind it lies his lived trauma. “At Dadar, I once saw a homeless man fall and get crushed between the platform and train. People just went back to their phones. Since then, I have never leaned at the door, never crossed tracks.” For Mrabhakar, beating the crowd isn’t for his convenience. It’s for survival.

4 Peak (hour) brotherhood

Dinesh Mohite, 38

Route: Titwala-CSMT

Staff at St Xavier’s College

Using trains since: 19 years

Dinesh Mohite (pink T-shirt) and his friends all travel together from Titwala to CSMT. Pics/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

Dinesh Mohite (pink T-shirt) and his friends all travel together from Titwala to CSMT. Pics/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

Dinesh Mohite has been commuting on the city’s Central line for nearly two decades. It’s where he found his second family, a brotherhood of fellow commuters who keep each other safe and share their daily joys and strife.

“We’re a group of 40 to 50 people. We occupy about eight full coaches between us,” Mohite tells us, “Everyone boards and gets off at different stations. We met each other on the train and became friends. Now we go to each other’s houses for Ganeshotsav, we are there for each other during difficult times, we organise birthday and retirement parties for each other. We are all like family to each other.”

The group has been travelling together for about 10 years or so, some members have joined in the last few years, some have been a part of the group since it was formed.

Anyone can join the group, says Mohite, “as long as we like their nature”.

When asked what precautions they take to ensure each other’s safety, he says, “We never hang outside [the coach]. We don’t hold seats for anyone, because they are on first-come, first-serve basis. But we want to ensure that everyone gets seated. For example, if someone gets on at Dombivli and has to get off at Thane, he will get the seat on priority. Once he leaves at Thane, maybe someone who has to get down at Ghatkopar will get a seat. We also keep rotating, so no one has to stand throughout the journey. It’s an unsaid understanding, people get up themselves.

“In 2008, I was in an accident myself. Swept along by the commuter rush at Masjid Bandar, I crashed into a pole. Thankfully, I was saved, but there’s not much that can be done to protect people in such a crush. No one hangs out of a train if they have other options. Sometimes, we try to pull people inside, but sometimes the trains are just so packed, an accident is inevitable.”

2008

year in which Dinesh Mohite was in accident that was close call

5 Trains are still best option

Rudra Thakkar, 20

Route: Mulund-Fort (by car)

Law student and intern

Using trains since: Six years

Rudra Thakkar loves Mumbai local trains but uses his car for comfort and presentation at his workplace

Rudra Thakkar loves Mumbai local trains but uses his car for comfort and presentation at his workplace

Rudra Thakkar, a law student and intern, usually drives from his home in Mulund to his law internship in Fort. Although he’s been using local trains since he was in Class 10, and praises them as the city’s fastest and cheapest commute option, he prefers to drive whenever the situation calls for more comfort, or when he has to look presentable for work.

“The only times I choose to drive is if I have a function to go to, I’m tired, or I have a lot of things to carry,” he says, “I know I can’t travel by train when I need my shirt to retain its ironed crispness.”

His reasons are practical: door-to-door convenience, uninterrupted air conditioning, the ability to carpool, and above all, personal space. But driving, he admits, comes with its own headaches. “With all the construction and rising traffic, sometimes I’m just a sitting duck in my car.”

When it comes to punctuality, he still trusts trains more. “Even with all the crowding and pushing, I can rely on a local to get me to Fort in about an hour.”

Thakkar plans to return to commuting on the locals when his college resumes in Juhu. “Driving in Juhu or Andheri is the worst. The roads are broken, there are potholes everywhere, unnecessary speed bumps — it’s exhausting.”

Ultimately, his commute is a daily balancing act between chaos and convenience.

‘Corporates need to collaborate with civic bodies’

Preeti Verma

HR Consultant with 22 years of industry experience

“Most organisations are moving to full-time work from the office. I know a lot of big organisations, like JP Morgan for example, are pushing towards full-time in-office work. There’s a lot of chatter about that. CEOs feel productivity and engagement are better when people are in office. They believe collaboration improves, supervision is easier, and efficiency increases when teams are physically present. It also allows for more standardised approaches across teams. Of course, this means higher infrastructure costs, but companies are still investing in office spaces, that show they’re serious about this shift.

I think people are the biggest driving force for any organisation. Companies should design policies that address the majority’s needs, even if they can’t help everyone. Companies usually adopt a standard approach across locations, especially within India. But, of course, cities like Mumbai and Delhi face bigger commuting challenges. That may mean adopting a nuanced approach based on geography. In some cases, companies can even collaborate with local authorities, especially since public transport falls outside corporate control. A partnership approach is essential for making commutes safer and more manageable.

Another strategy I see being used is that companies are now targeting tier-2 cities like Jodhpur and Warangal to allow people to work closer to home. This eases pressure on metro cities and reduces the need for relocation and long commutes. It also helps with resource management.

Cityflo: The great big alternative?

Jerin Venad,

CEO & Co-Founder at Cityflo; HR Consultant with 22 years of industry experience

Cityflo, an app-based bus service, has turned out to be a reliable alternative for the Mumbai commuter. Citizens can avoid the train rush and travel in air-conditioned comfort without the hassle of owning a private vehicle.

The service also offers app tracking, direct routes and safety. Jerin Venad, the CEO, shares: “We’re focused on building a scalable, high-quality mobility network that keeps pace with the growing need for reliable daily transport across MMR. With over three million rides served last year, we continue to expand on high-density corridors while piloting new transit formats to better match evolving commuter needs.

“The run times have increased across the city, as expected in a region where vehicle density over the last five years has grown by 25 per cent and private vehicle ownership grew by 15 per cent last year alone. A single Cityflo bus can replace up to 25 car trips daily during peak hours, and if scaled meaningfully, this model could reduce road space by up to 75 per cent on certain routes, which means faster journey times for everyone. Our effort is to make this shift frictionless, by ensuring on-time performance, flexible time slots, and a ride experience good enough to convince car owners to make the switch.

“Large infrastructure projects like the Mumbai Metro and Atal Setu are critical enablers to our goal. We’re actively integrating our services with this evolving landscape, through direct commuter routes as well as first and last mile connectivity around upcoming metro stations and transport hubs. We’re also closely aligned and with public initiatives under the Gross Cost Contract models to operate clean, efficient public transport at scale in partnership with the government.”

How train apps can help warn commuters

M-INDICATOR

With over 1 crore downloads, M-Indicator has become synonymous with train travel in Mumbai. Launched in 2010 by Sachin Teke, the app started during the Nokia Java phone era and has since evolved into an essential tool for local commuters offering train schedules, platform numbers, and live updates.

“We were the first to do it,” says Teke, developer of the app. “We’ve consistently focused on the app for 15 years and maintained the data. That’s why people trust us. It’s brand loyalty.”

After the recent Mumbra train incident, the app is now gearing up for a major update: AI-powered safety alerts. “Right now, commuters can post in our chat section, but replies take up to 15–20 minutes. We’re now launching AI-based chat responses,” Teke shares. “If someone flags a safety issue, it will instantly alert others travelling on that same route — even before authorities know.” With AI integration, the app will also be able to verify incoming user alerts by scanning for multiple reports of the same issue. For a city that runs on the rails, M-Indicator remains vital.

YATRI

Yatri — the official Mumbai local app backed by the Indian Railways — is quietly laying down its own tracks. With just over 10 lakh downloads, Yatri’s co-founder Reeva Sakaria points to its relative newness. “We’ve only been around for over three years. If you compare it with the others in the market, it’s just a legacy gap, not one of success” she says.

What sets Yatri apart is its investment in real-time accuracy. “We’ve installed GPS devices on every single local train,” Sakaria explains. “Our data isn’t crowdsourced — it doesn’t show you an ETA based on speculation.”

In the aftermath of the Mumbra train mishap, Yatri focused on timely communication. “We pushed alerts across social media and within the app. We’re now working on showing trains likely to be crowded — though we lack access to CCTV or heat maps, we’re doing what we can within our limits,” she adds.

As for user interface, Sakaria acknowledges the loyalty commuters have toward older apps. “People have been using the same UI for over 14 years. But we’re building our own identity.Our focus, rather, is on designing a more intuitive, user-friendly interface for the audience.”

Looking ahead, Yatri hopes to become a one-stack national commute app. With growing tech infrastructure, Yatri may be playing catch-up but it’s definitely

on track.

7

Avg no. of deaths per day across CR and WR

*Source: GRP report, 2025

By Tanisha Banerjee, Akshita Maheshwari & Saesha Deviprasad

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!