A Pune-based design expert is tracing the journey of the humble kavadi as a sought after fashion and decor accessory

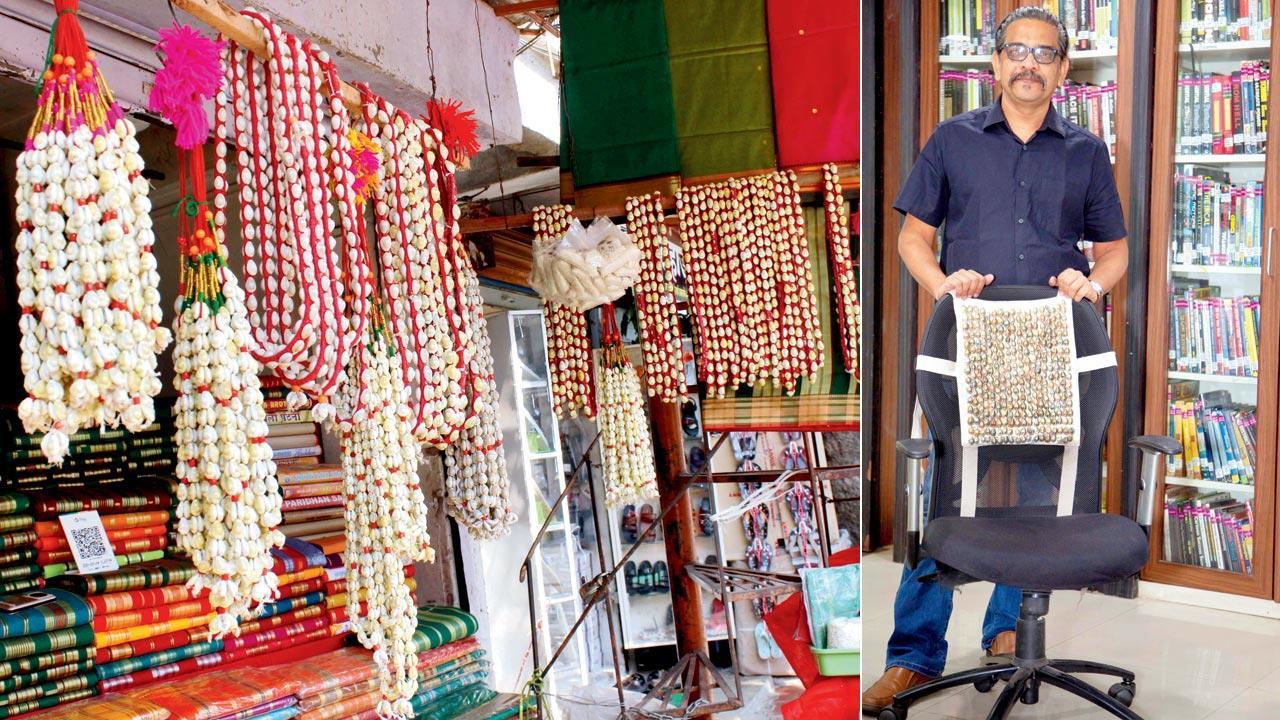

Traditional cowrie accessories seen at a market in Tuljapur; (right) Nitin Hadap with a cowrie-embedded office chair

![]() It's in Bhavani temple, situated in the historic Pratapgad, that Nitin Hadap, then a toddler, first encountered the cowrie—revered, polished seashells used in the worship of the devi Bhavani. As he belonged to the head priest family, the fort precinct was his residence, and it brought him in touch with folk singers (Gondhalis) who offered a garland of cowries (kavadis) to the Devi. The self-whipping Potraj also wore a chain of cowrie shells. Hadap has vivid recollections of using the cowrie as dice in the indoor chausar (saaripaat) game. Little did Hadap know that the object—a monetary system no longer in existence—will feature in his paper titled, Cultural Studies of Cowrie Accessory Design Traditions: Diversity and Current Design Practices in India, recently presented at the Seventeenth International Conference on Design Principles and Practices, hosted by the Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon, Portugal.

It's in Bhavani temple, situated in the historic Pratapgad, that Nitin Hadap, then a toddler, first encountered the cowrie—revered, polished seashells used in the worship of the devi Bhavani. As he belonged to the head priest family, the fort precinct was his residence, and it brought him in touch with folk singers (Gondhalis) who offered a garland of cowries (kavadis) to the Devi. The self-whipping Potraj also wore a chain of cowrie shells. Hadap has vivid recollections of using the cowrie as dice in the indoor chausar (saaripaat) game. Little did Hadap know that the object—a monetary system no longer in existence—will feature in his paper titled, Cultural Studies of Cowrie Accessory Design Traditions: Diversity and Current Design Practices in India, recently presented at the Seventeenth International Conference on Design Principles and Practices, hosted by the Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon, Portugal.

The cowries, referred to as “kavadi mol”, which translates to least value currency, has won him the Emerging Scholar Award at the conference. He was recognised for unravelling the cowries that are deeply rooted in Maharashtra’s religious practices, faith-based conventions, cultural exchanges, and social life for the last

2,000 years.

Goddesses like Renuka, Yallama, Mariae, Bhavani, and Mahalakshmi are worshipped with cowrie jewellery. Devotees (Jogtini, Matangi, Bhutye) describe the deities’ robes and cowries in grand terms: “Piwala pitambara devila nesanyala/ Kawadyacha shingar ambana kela [The Goddess adorns the yellow garment/ the Goddess decks up in cowrie jewellery].”

“The seemingly undervalued cowries have enriched me as a scholar. I have ‘cashed in’ on these out-of-currency shells,” Hadap adds in jest, just as he prepares for the upcoming book modelled on the paper. “Cowries are part of India’s collective consciousness. I intend to research their social role in and out of Maharashtra, especially states like Rajasthan, Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Bengal and Orissa. There is a lot on my plate for the next two years,” says Hadap, who is professor of Fashion Design at the Symbiosis Institute of Design.

Hadap has travelled all over the Konkan region for cowrie shells, and has also collected data from field work around the pilgrim temples (shaktipeethas) like Kolhapur and Tuljapur. As most shells come to Maharashtra from Gujarat’s coast, Hadap has negotiated that route too, of course in an interrupted time cycle because of pandemic restrictions. The lockdown protocols, though, didn’t affect his cowrie research for a different reason—he virtually visited most iconic history/culture museums to assess the global footprint of the cowrie.

Folk costumes and traditional designs have always fascinated Hadap, as evident in his 2015 book Pura Fashion, which traces fashion styles in Indian history, including flashes from the Indus Valley civilisation. The book focuses on the changes in dress and drapery in ancient India; conjures up ancient periods by reconstructing period costumes based on sculptural remains and paintings.

Hadap’s fascination for the surface ornamentations dates back to his fine arts graduation in Pune’s Abhinav Kala Vidyalaya and a diploma in Art Education from Sir JJ School of Art in Mumbai. In fact, his interest in Indian culture prompted him to study indology in a master’s programme, which in turn paved the way for his doctorate in Composite Motifs in Indian Art from Deccan College (Pune).

During his research in the domains of ancient history and archaeology, Hadap was fixated on natural objects used as fashion accessories. For instance, he presented and published a paper on Pagdis (headdress/gear) of Maharashtra; the protective robe Chivar also captured his bandwith at one point, and so did the nail cutter, other ornate cutters and shaving equipment. He has done a paper on traditional eco-sensitive “ethical” fashion trends, which have a reduced carbon footprint. Similarly, he studied the Konkan woodwork art tradition under the support of the Nehru trust for the Victoria and Albert Museum.

After he is done with cowries, he will move towards peacock feathers, bamboo, kumkum pigment, betel nuts, egg shells, and the mangalsutra.

“In 1990, I was lucky to have one personal interaction with famed painter SH Raza, who insisted that a painter should know his own culture in depth. That thought has stayed with me and has guided my research on objects. I find that objects tell a story of the past social mores and etiquette. They also offer a window to understand political-social-cultural perspectives of the times.” Hadap gives the example of the winged and fishtailed hyper-hybrid animal motifs on wall toranas and railings, as well as jewellery which indicate a search for a shield from the evil eye.

Cowries have also been used in different cultures as an auspicious element against evil spirits, as Hadap’s paper suggests. The Bastar region, marked by an abundant use of cowries by the Muria and Dhurwa tribal communities, demonstrates the use of cowrie amulets for women. Garlands with interwoven twigs and cowries are commonly tied around babies’ necks. The Banjara gypsies decorate their bullocks with cowries, so as to ward off hostile eyes. In many parts of India, cowries are treated as lucky charm objects to counter illnesses or produce good vibrations in diseased parts of the body. In some regions, the custom of offering five cowries at the village boundary symbolises a purification gesture, usually after the end of a smallpox epidemic.

Hadap says cowries fascinate him because they have had colourful multifaceted avatars in different social settings. “It is an exciting ritual object which transcends time and geography,” he shares. As far back as 17th century BC, cowries were found on the waists of female figures in the art depictions from Egypt—the gold cowrie shell girdle is well-known. The Egyptian canon called Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (18th century), includes tests to distinguish the fertile from the infertile women. In ancient Egypt, girls and young women wore cowrie girdles to protect their future fertility; they also wore cowries during pregnancy to protect the unborn child before delivery. In China, cowrie was used as a stamping tool, as revealed in an excavation in Jiangsu province. In Northern India, Orissa and Bengal, as well as Pakistan and Afghanistan, cowries were widely used as “small money” as against the “big money” of silver.

“As vividly illustrated in many accounts of early Indian society, the cowrie trade is also connected to slave trade, linking the Indian Ocean with Africa and the Atlantic slave markets. Also, the role of cowrie shells in the Silk Road has not been much explored,” states Hadap, which leaves a huge expanse for the new

cowrie researcher.

Hadap feels his research is as much about the past, as it is focused on the cowrie design application for the future. He factors in modern use of cowries in footwear, neckpieces, bikini wirework, Vastu peace-inducing objects, and belts. Cowrie’s utility in the light design field is also achievable, as it is a translucent material. He also sees scope in furniture designs, which can be tailored to health/lifestyle needs.

He foresees cowries used abundantly in car chair seat cushions to serve the human body’s acupressure points. The accessory is ergonomically suitable and works best on long drives. Cowries can replace the wooden and plastic beads in the back cushions in general, as they can be drilled easily without causing harm to the environment.

Mapping cowrie

. In the Erukala tribe of Andhra Pradesh, cowries are included in the gifts given to the bride’s father.

. In Punjab, the charkha adorned by cowries was given as a gift during the marriage ceremony to the bride by her mother.

. In Orissa, a basket called ‘Jagthi Pedi’ is full of useful day-to-day objects and cowries, given as a gift to the bride.

. In Rajasthan, the bride wears a dress adorned with cowries during the first night in the Meena community.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!