It appears that only movies that portray the State darkly, refer to caste conflict or treat religious minorities with empathy stir the Central Board of Film Certification into calling for cuts

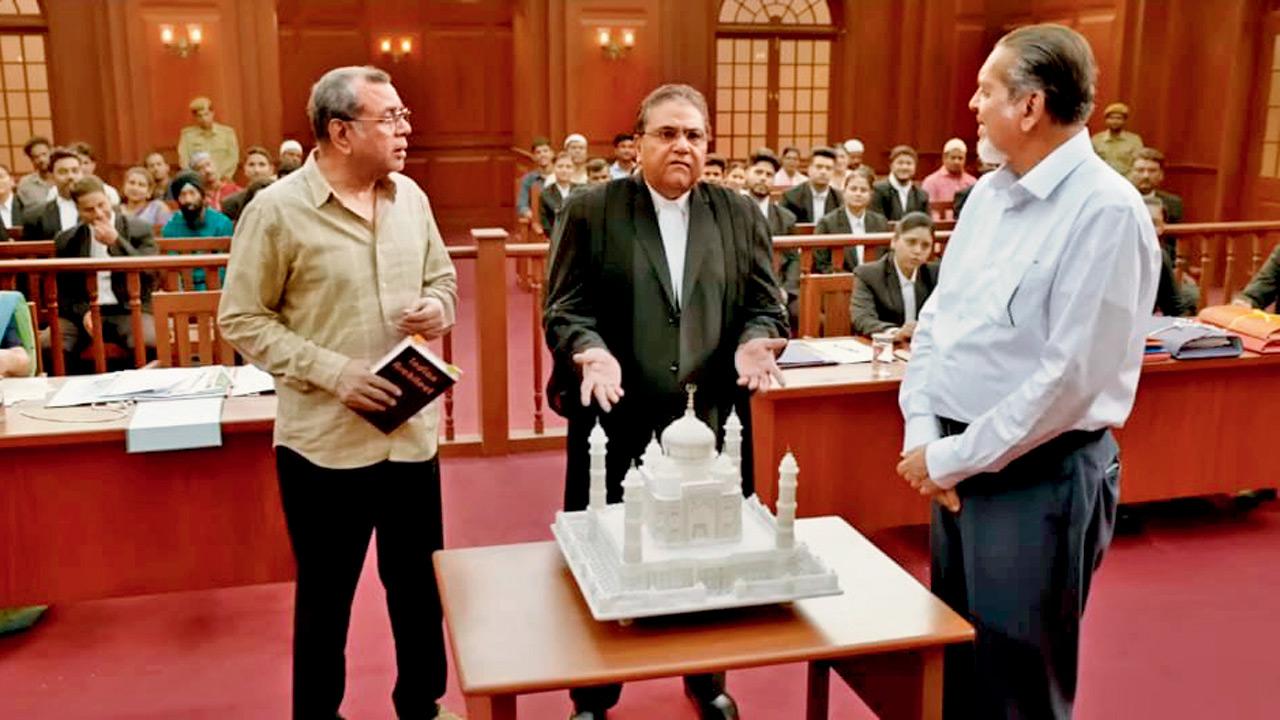

A still from the trailer of The Taj Story, an upcoming film starring Paresh Rawal and Zakir Hussain

The sparkling dome of the Taj Mahal in Agra has been witness to the Bharatiya Janata Party, the reigning patron of the rewriting of history, winning the Lok Sabha elections here since 2009. Agra is indeed the city that should be excited over watching the film The Taj Story, which, due to be released this week, recycles the discredited theory that Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan converted a temple into a wondrous monument of love — Taj Mahal — to his wife Mumtaz Mahal.

The sparkling dome of the Taj Mahal in Agra has been witness to the Bharatiya Janata Party, the reigning patron of the rewriting of history, winning the Lok Sabha elections here since 2009. Agra is indeed the city that should be excited over watching the film The Taj Story, which, due to be released this week, recycles the discredited theory that Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan converted a temple into a wondrous monument of love — Taj Mahal — to his wife Mumtaz Mahal.

Instead, there’s a sense of foreboding among members of the Tourism Guild of Agra. Its former president, Rajiv Saxena, said The Taj Story resorts to fiction to provoke emotions and distort history by disregarding archaeological facts and textual evidence. “We will not allow the Taj Mahal to be ridiculed or diminished by unfounded claims. The Tourism Guild of Agra strongly condemns, rejects and distances itself from such misleading narratives.”

Saxena’s sense of history is lacking in members of the Central Board of Film Certification — sardonically dubbed the ‘censor board’ — who cleared the Taj Story. They ostensibly chose to gloss over the judiciary’s repeated dismissal of petitions seeking to have the Taj Mahal declared a temple, and also the Archaeological Survey of India’s assertion, in a 2017 affidavit to an Agra court, that the Taj Mahal is a tomb, not a temple.

Debunked has also been The Taj Story’s attempt to create a mystery regarding the 22 locked rooms in the monument’s basement. These rooms, ASI officials have said, originally constituted an arched corridor to which doors were attached at a later date, to better regulate the flow of tourists. No inscriptions are in these room, nor images of any Hindu deity. These details establish that The Taj Story is one big lie about India’s past.

All imaginings of the documented past are fictitious or grossly exaggerated, in the sense that these couldn’t possibly have happened in the manner usually depicted in Indian cinema. These portrayals, until the last 10 years, were largely romances or expressions of valour and patriotism, offending none. But now, as in politics, so in films, history is being relentlessly mined to manufacture hate. For instance, The Taj Story’s trailer portrays Shah Jahan as a destroyer of temples, incapable of conceiving as exquisite a monument as the Taj.

The Taj Story is an addition to the list of films in which Muslims are projected as villains who perpetrated extreme violence on Hindus or are a drag on the nation. Think Chhaava, The Bengal Files, The Udaipur Files, The Kashmir Files, The Kerala Story, Hamare Baarah… the list is long.

Anti-Muslim films are often justified as dramatic renderings of recorded histories and legends, whether authentic or dubious. Yet the censor board’s seemingly laissez-faire attitude to films on the past and present of Muslims is in sharp contrast to its queasy sensitivity regarding depictions of the State’s selective brutality and the malaise of casteism, which too have been extensively documented.

Take Honey Trehan’s Punjab ‘95, a biopic on human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra, who was disappeared even as he was investigating the abduction and extra-judicial killings of citizens by the Punjab Police. Submitted to the censor board in 2023, it’s still stuck there, with 127 cuts demanded of it. “The 127 cuts are not on the film but on the democracy,” Trehan said in an interview.

Sandhya Suri’s Santosh narrates the story of a police constable who discovers that a Muslim has been wrongly accused of raping and murdering a Dalit girl. The weaving together of police conduct and the victimisation of Dalits and Muslims had the mighty censors demand, according to Suri, cuts running into several pages, effectively aborting Santosh’s screening. Homebound, celebrating the camaraderie between a Dalit and a Muslim, escaped with just 11 cuts, perhaps because the two friends endure discrimination without challenging the State, as is expected of their communities.

Nineteenth-century social revolutionary Jyotirao Phule railed against casteism and Brahminism in his writings, but the censors insisted on modifications to his biopic, ordering that caste names and a reference to “Manu’s system of caste” be removed. In Dhadak 2, love trumps caste but not the censors, who sliced scenes from the movie.

Over-the-top platforms don’t require a priori approval for streaming a film, but they have taken to self-censoring themselves, with the severity of the censor board, lest Hindutva trolls entangle them in court cases or the BJP government blocks them. For instance, Netflix financed Dibakar Banerjee’s Tees, a story of the Pandit-Muslim relationship in Kashmir, but shied away from platforming it. SonyLIV reneged on its announcement to screen Arun Karthick’s Nasir, which narrates the experiences of a Muslim salesman in a city reeling under Hindutva.

It’d seem the censor board, like Mahatma Gandhi, has “three monkeys” — or principles — for judging a film. Does it portray the State darkly? Does it refer to caste conflict? Does it treat Muslims with empathy, without alluding to their villainy? A yes to any of these three questions will have the censors scissor the film to feed the dystopian fantasy of a new India, where hatred is entertainment.

The writer is a senior journalist and author of Bhima Koregaon: Challenging Caste.

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!