A life-long admirer of Vinoba Bhave revisits the Bhoodan movement in a fresh documentation that celebrates the sentiment of surrendering the personal for the larger public good

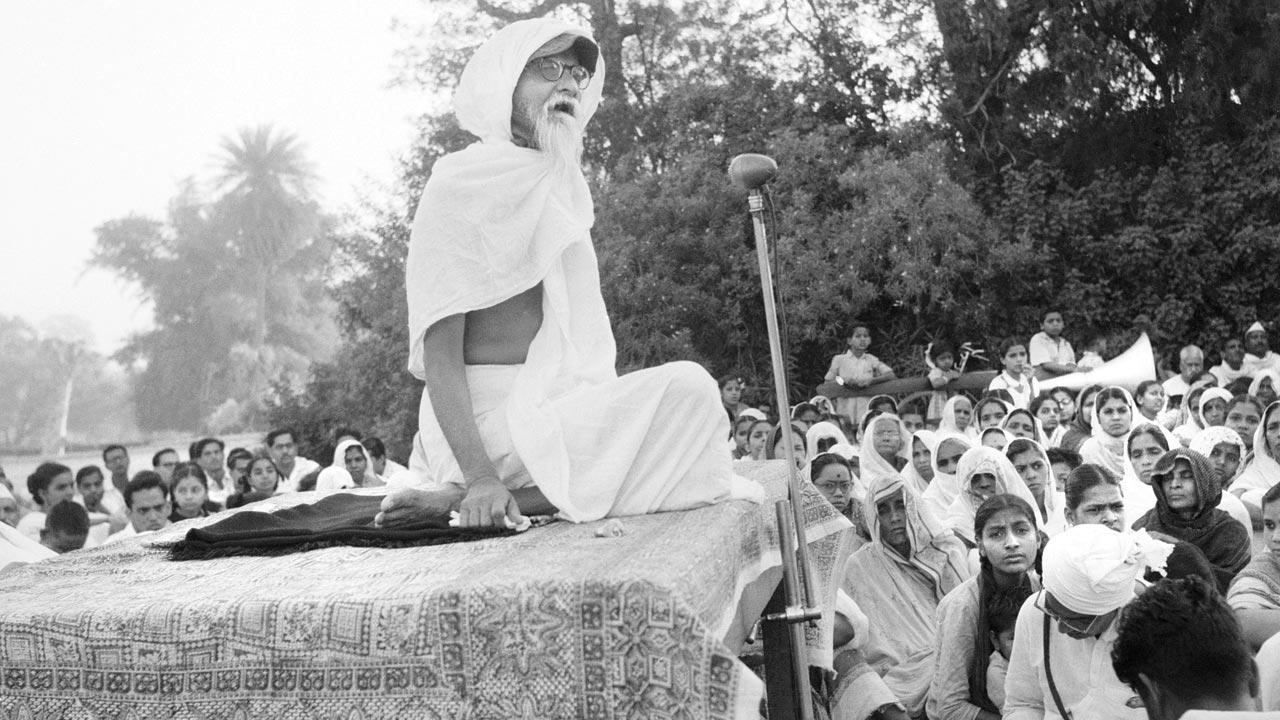

Vinoba Bhave addressing a gathering in Agra, 1960. Pic/Getty Images

![]() On May 16, 1951, exactly 71 years ago, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru expressed wonderment in the Lok Sabha about Vinoba Bhave’s courageous start of the Bhoodan movement in the politically volatile Pochampally village in the Nalgonda district of Andhra Pradesh. PM Nehru said the physically-weak and unarmed Vinoba had succeeded in the equitable distribution of land in a politically-sensitive region, where strong army contingents have found it difficult to initiate law and order.

On May 16, 1951, exactly 71 years ago, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru expressed wonderment in the Lok Sabha about Vinoba Bhave’s courageous start of the Bhoodan movement in the politically volatile Pochampally village in the Nalgonda district of Andhra Pradesh. PM Nehru said the physically-weak and unarmed Vinoba had succeeded in the equitable distribution of land in a politically-sensitive region, where strong army contingents have found it difficult to initiate law and order.

PM Nehru was not the only fan of Vinoba’s non-violent land reform; the entire nation was astounded by his sheer faith in the idea of danam samvibhaga (equal sharing), which he applied not just in terms of land distribution, but also with regard to intellect, time and physical labour. No wonder, Vinoba’s walking tour (1951-1972) across the length and breadth of India yielded fantastic cooperation from landlords, peasants, landless labourers, politicians across parties, law enforcement agencies and the news media of a newly-independent India. Never earlier and nowhere else in recorded history have people donated land—47 lakh acres/4.7 million acres—without coercion or force. The distribution of 2.5 million acres to the landless is a feat in itself.

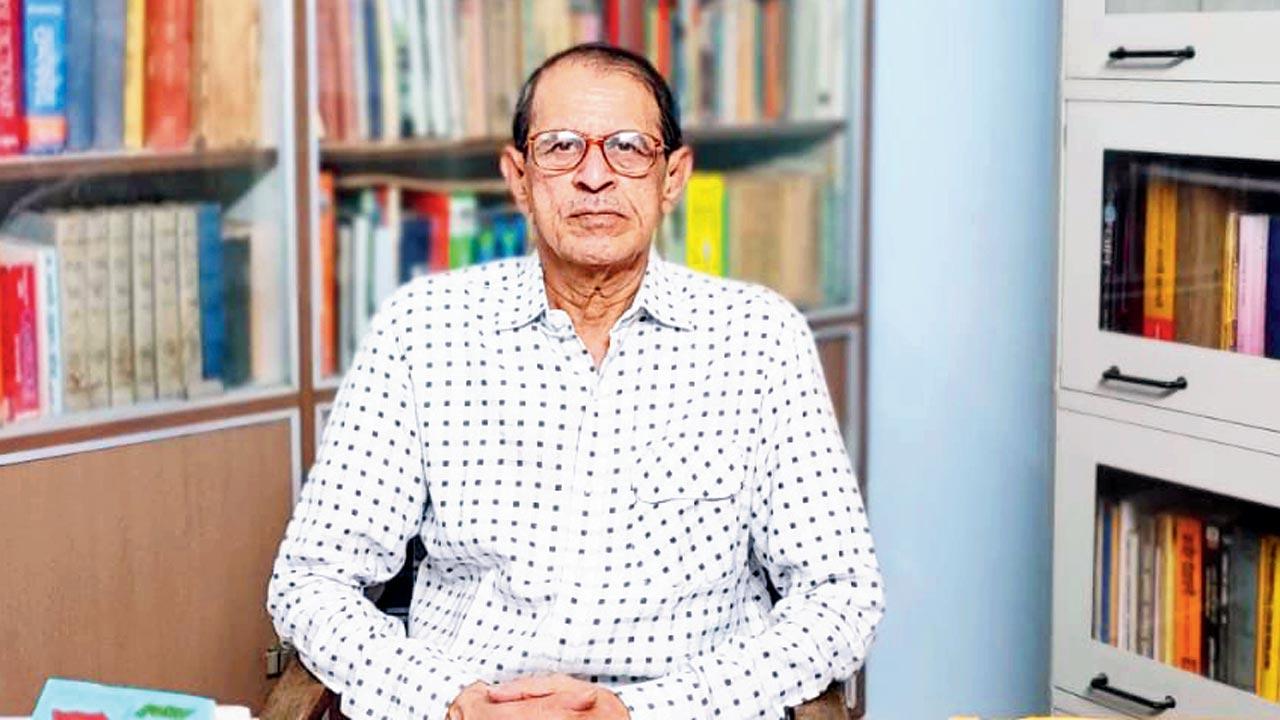

The sheer scale and impact of the bloodless revolution inspired Nagpur-based Gandhian scholar Parag Cholkar, 71, to document the Bhoodan Gramdan experiment in three languages. While his Marathi book, Avaghi Bhoomi Jagadishachi, just hit the stands, he first chronicled it in Hindi (Sabai Bhoomi Gopal Ki) in 2010; the English version, The Earth is The Lord’s, was penned in 2016. The Hindi project ran into a thousand pages, while the English and Marathi editions are compressed to 500. “Had I known other Indian languages, I would have rendered the story in each of those, as Bhoodan touches every Indian’s life,” adds Cholkar.

Gandhian scholar Parag Cholkar has documented the Bhoodan Gramdan experiment in three languages. “Had I known other Indian languages, I would have rendered the story in each of those, as Bhoodan touches every Indian’s life,” he says

Gandhian scholar Parag Cholkar has documented the Bhoodan Gramdan experiment in three languages. “Had I known other Indian languages, I would have rendered the story in each of those, as Bhoodan touches every Indian’s life,” he says

At this point, Cholkar is prepping up for two new projects. While one tome is devoted to Vinoba’s economic ideas like Swadeshi homegrown industries and promotion of Khadi Gramodyog, the other concentrates on letters written by the leader, while touring India’s countryside. Cholkar sees an immense educational value in the correspondence continued by Vinoba despite being part of a social churning. “Being a true disciple of Mahatma Gandhi, Vinoba amplified, executed and personified Gandhian ideals throughout his life. Be it his outlook towards South Asian neighbours or his philosophy of upskilling of traditional rural craftsmen or his appreciation of the farmers’ land-related woes, Vinoba presented an inclusive peace-driven progressive worldview.”

Cholkar says his research honours Vinoba’s ahimsa in thoughts and actions. “Isn’t it amazing that Vinoba resolved many trying land ownership conflicts in different corners of India without exerting any political pressure or using any unfair means? He brought warring parties face to face outside a conventional court.” Cholkar says the Bhoodan movement celebrates the power of dialogue and collaboration.

The book awakens us to the moral authority wielded by Vinoba, unmatched in current-day India, which enabled him to resolve conflicts at family-community-village levels. Be it about feuding brothers or litigating labourers or privileged princely state patrons, Vinoba treated each bhoodan with equal sensitivity. Little wonder that the movement received support from diverse corners—four churches in Kerala pledged support; the Central province, including Vidarbha, birthed a legislation to facilitate land distribution; Saurashtra and Orissa followed suit on the legislation route. West Bengal MLA Charuchandra Bhandari resigned from the post and dedicated his life for the Bhoodan cause. In fact, the movement is a celebration of the unnamed faceless volunteers who believed in Vinoba’s way of life.

After Mahatma Gandhi’s demise (1948), Vinoba was the father figure who attracted scores of volunteers. In this context, the anecdote in Deoghar (Bihar) is telling. When Vinoba appealed to the Brahmin priests in Deoghar to open the Shiv temple to all castes, including Dalits, an angry mob attacked the leader with sticks. Bhoodan volunteers formed a protective circle around Vinoba, even as the priests became more aggressive.

Cholkar devotes a special chapter to the rank and file volunteers whose health suffered in the Bhoodan walking tours. Often volunteers would reach a village in the night and sleep hungry. First-aid boxes were not handy in the countryside, which is why ailments and bruises/sores remained unattended. Women team members suffered their special share of inconveniences. Each state’s dietary preferences had to be uncomplainingly stomached by Vinoba’s followers. One instance at Santhal Pargana, Jharkhand is eye-opening. A bullock cart was lugged uphill by 10 volunteers, while climbing a forested patch in the night hours. After the dangerous journey, the team rested overnight inside a remote school. They feasted on roasted corn, the only available staple.

The Nagpur-born Cholkar has been a Vinoba fan right from his school years in Akola. After getting a degree in BTech (1974), he devoted one year to Sarvodaya movement at Wardha. He watched Vinoba from a distance in those days, especially when he sought permission to fully devote his life to Sevagram. But Cholkar couldn’t get close to the leader. He later worked as a banker for a decade, but sought premature retirement in 1985. Since then Bhoodan, Gramdan and Vinoba’s literature have been the focus of his writings. He post-graduated in Gandhian thought and later did a doctorate in Gandhian theory of the state. He has also edited Sarvodaya’s Marathi fortnightly Samyayog and oversaw the Paramdham Prakashan. In 2008, he became a visiting fellow in Vinoba studies at the Gujarat Vidyapeeth. A major portion of the research was accomplished on the campus.

Being an insider, Cholkar was chosen by the Sarva Seva Sangh—the organisation which spearheaded the movement—to represent Vinoba for the modern Indian. Gujarat Vidyapith showed interest in publishing it. Cholkar preferred “an independent academic institution over a partisan organisation”. Cholkar feels Vinoba is too vast a figure to be limited to the Gandhian followers. Interestingly, the Time magazine had Vinoba on its cover in May 1953; London Times applauded the spontaneity of his padayatras. Japan’s socialist leader Yoshiko Hoshino said Bhoodan was a novel revolution premised on cooperation and fellow feeling.

Land is the most commercialised resource in today’s India. Land ownership has led to intense riots in rural and urban milieus since Independence. Cities such as Mumbai witness prolonged political confrontations over real estate. Cholkar’s documentation brings to life an amazingly mass-scale organic land/village donation exercise. He also underlines Vinoba’s truthfulness and honesty while accounting for the donated land. When zaminadars or princely state chieftains donated land abundantly, Vinoba immediately cross-referenced the ownership records, so as to ensure fair play. While he supported cooperative farming on donated land, he was wary of co-ops formed under the name of unlettered farmers. He didn’t want land to be under the invisible control of the moneylender or the middleman. He wanted a selfless genuine response to inspire the daan—an ideal that’s worth revisiting today.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!