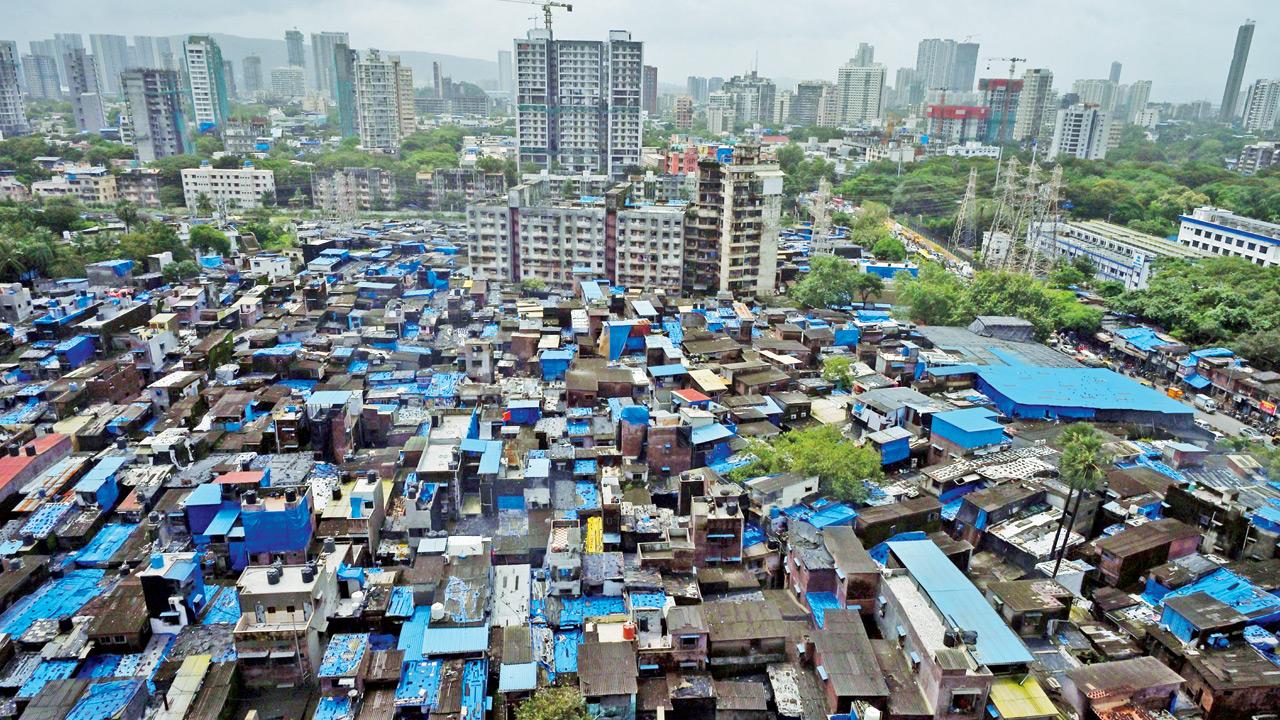

A politically incorrect proposition by Architect Jagdeep Desai to all concerned, proponents and opponents, to the redevelopment proposal in one of the largest slums of Asia

Dharavi, one of Asia’s largest slum housing clusters is located in the heart of Mumbai. FILE PIC/ ATUL KAMBLE

Most development plans are for five or ten years. This one is a seven-year, R1-lakh-crore project to redevelop Dharavi — popularly referred to as one of Asia’s largest slum.

Most development plans are for five or ten years. This one is a seven-year, R1-lakh-crore project to redevelop Dharavi — popularly referred to as one of Asia’s largest slum.

Rs 1 lakh crore may still be too little, considering all the associated costs: transit rentals, construction, operating expenses, and more.

Take just the task of constructing 30,000 flats and thousands of small industrial spaces — that alone would likely exceed the current budget.

By the way, Orangi Town in Karachi and Ciudad Neza in Mexico have larger populations, so let’s not assume Dharavi is the biggest slum in Asia — or the world.

We’re told the redevelopment plan will integrate residential, commercial, and industrial zones, rehabilitate residents, and support livelihoods through dedicated spaces for small industries.

Okay, okay… what’s new?

As usual, there’s talk of “preserving open spaces,” such as Mahim Nature Park, which, conveniently, is outside the redevelopment zone anyway.

And this project is being benchmarked against Singapore’s best practices in slum rehabilitation.

Small problem: Singapore flattened its slums — some say mercilessly — in the 1970s. It launched a massive urban renewal program to tackle housing shortages.

The Housing and Development Board (HDB) led the charge, armed with the Singapore Land Acquisition Act of 1967, which enabled compulsory land acquisition for rapid redevelopment.

But that’s nothing compared to what happened to a true urban marvel — Kowloon Walled City, or Hak Nam.

Originally a military settlement built by the Qing government in the 19th century, it eventually became a dense and lawless enclave. During World War II, its stone walls were demolished by the Japanese.

What followed was chaos.

By 1987, the British and Chinese authorities decided it had to go. In 1993, demolition began. Over 500 interconnected buildings, constructed without architects, engineers, or safety codes, were brought down.

Sunlight rarely reached the inner labyrinths. Crime, illegal gambling, drug activity, and food factories (under horrifying conditions) flourished. Still, it was home to 30,000+ people.

Many residents were rehoused by the Hong Kong Housing Authority — some willingly, others forcibly.

Very much like our current situation.

Incidentally, the average tenement size was around 23 sq m, just like in Dharavi today.

But here’s the twist: Kowloon wasn’t redeveloped into more high-rise apartments. It was transformed into the Kowloon Walled City Park — a public space with preserved heritage, interactive exhibits, and open skies.

No ‘sale component’

No 21 or 42 sq m rehab flats.

No glass, steel, concrete jungle.

Cut to Dharavi

Reports say it’s going to be the usual story — exploiting the Floor Area Ratio (FAR) and Floor Space Index (FSI) of the land.

The 600 acres of Dharavi will be filled with the typical steel, glass, aluminium, and cement-concrete structures. And the missing infrastructure? That will probably be “discovered” and added miraculously a few years later.

As always, lakhs of ‘eligible’ and ‘ineligible’ residents will be moved to temporary accommodations, only to be brought back after years, maybe.

There is no binding policy that mandates residents affected by slum redevelopment be resettled in the same area they once lived.

People commute hundreds of kilometres every day for work or education. A few extra kilometres? That’s considered normal.

To contest relocation, Project Affected Persons (PAPs) must prove that the site they’re being shifted to is so uninhabitable that no reasonable person can live there — as observed by the Bombay High Court in 2023, in a different PAP case within Mumbai.

There are policies in place

Maharashtra PAP Rehabilitation Act, 1999

National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy, 2007

PAPs can even be given lump sum compensation to settle wherever they choose — arguably for a better quality of life.

A few years ago, for the Hyderabad Metro, instead of incentivising TOD (Transit Oriented Development) around a 500-metre radius from stations, authorities reportedly offered land outside the city for the contractor to develop — a smarter, more sustainable model.

Similar ideas could spare the state and developers from building temporary accommodations on salt pans, mangroves, and ecologically sensitive zones, only to replace them later with “permanent” buildings and free-sale towers.

Real urban development is not just concrete, steel, and glass. It must be measured by the quality of life it brings to its residents.

Mumbai has a chance here to think differently.

Not going down the conventional redevelopment route might actually be less expensive for everyone. It will save our salt pans. Our mangroves. Our air quality.

Imagine a Kowloon Walled City Park-style transformation: Dharavi turned into a vast public park and theme park, complete with supporting facilities — local housing, guest accommodations, medical centres, repair hubs, maintenance services.

By the way, Mumbai is one of the few major metros in India that lacks a large municipal public park accessible to all. Sanjay Gandhi National Park is a reserved area with limited public access.

Compare it to Kolkata...

Eco Park – 480 acres

Maidan – 400 acres

Rabindra Sarobar – 192 acres

Central Park Salt Lake – 152 acres

Subhash Sarobar – 73 acres

Victoria Memorial Grounds – 64 acres

In the global perspective

Disney’s Animal Kingdom in Florida spans over 500 acres, roughly the size of Dharavi.

It cost Rs 300 crore to build. It generates about Rs 3000 crore in revenue per year.

It’s not too late.

The idea is simple

Transform Dharavi into a multi-use, open urban zone — with special economic, education, entertainment, medical, sports, and non-polluting industrial units. Maybe even a bird park, like Jurong in Singapore. Or a massive open-air aquarium. The possibilities are endless. And it would be a rare, open green space — in the very heart of Mumbai.

No doubt, this idea will likely be ignored by those wedded to the usual redevelopment model. But in the public interest, it deserves serious consideration.

In the future, we may get some open spaces — but only if today’s administration and corporate consortium have the foresight and vision to build something extraordinary.

Of course, the maximum allowable FAR and FSI will still be available for “use”, as always.

And by 2032, we’ll have a redeveloped Dharavi — one way or another.

Unless legal delays intervene.

Jagdeep Desai is an architect, academic and founder trustee chairman of the Forum for Improving Quality of Life in Mumbai

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!