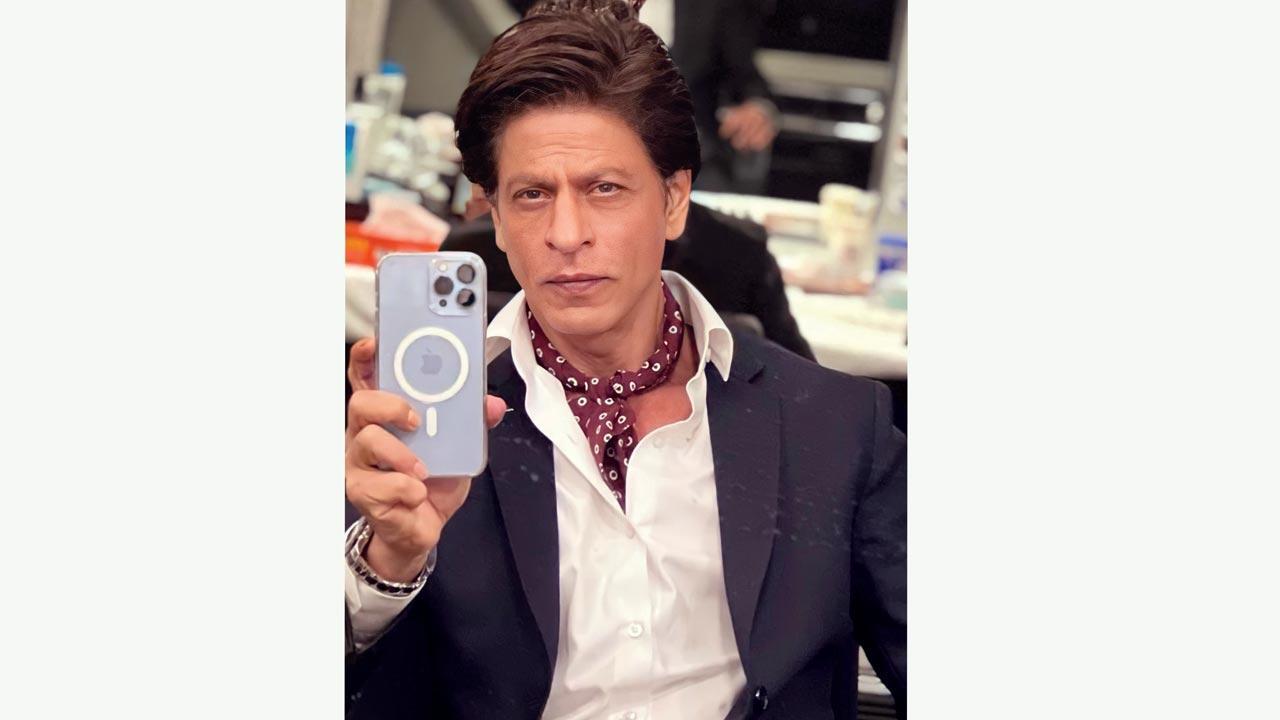

Thirty years after the Hindi film industry welcomed SRK into the movies, his legacy shines on. A social scientist, a documentary filmmaker, and his biggest fan deconstruct the myth and madness of Bollywood’s baadshah

Illustration/Uday Mohite

On our table at the Aquarius poolside restaurant of The Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, actor Shah Rukh Khan dominates the conversation. Writer-economist Shrayana Bhattacharya, who we are here to meet, teases the mid-day photographer, “Please, take good pictures… you never know, Shah Rukh might see.” It’s been over half a year since her book Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh—already a bestseller—made it to bookshelves, and just about two months since her fortuitous visit to Mannat to meet the incidental subject of her book. “I am very happy to report that I didn’t faint. He is really presidential,” she shares. On June 25, when Khan, Bollywood’s undisputed Baadshah, completed 30 years in the movies, Bhattacharya was among those who celebrated it with her two bits on social media: “An artist whose images and interviews changed the way I approach economics, writing, social science research, gender studies and myself. He is more than a ‘star’, he is a universe of concepts and meaning,” she wrote, with the hashtag #pictureabhibaakihain.

Bhattacharya tells us now, how she dislikes words like “star-struck”—often used callously for the actor’s admirers—to describe her work as a social scientist. “I am too ordinary a fan,” she confesses. What she was purely interested in, is telling the story of “what happened to women in post-liberalisation India”. “India is one of the few countries where as we have grown [economically], women’s employment drastically declined. Today, we are at the bottom five [when it comes to women’s employment],” says Bhattacharya. “I wanted the reader to understand data, the different explanations, the technical substance of it, but of course, I wanted to do it in a way which would not bore them to death. It had to be interesting and accessible, and I was very committed to that for a long period of time.” As luck would have it, SRK came into the picture.

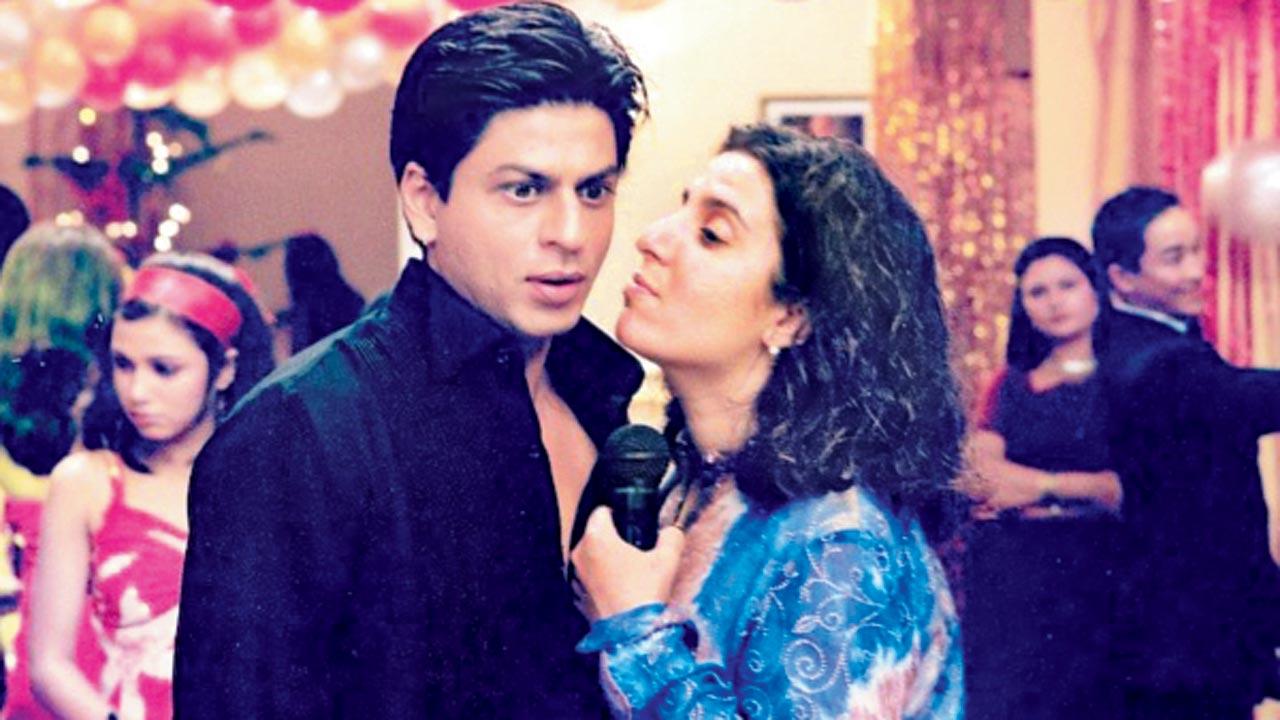

During the making of The Inner World of Shah Rukh Khan, 2004. On the set of Main Hoon Na, with director Farah Khan

During the making of The Inner World of Shah Rukh Khan, 2004. On the set of Main Hoon Na, with director Farah Khan

Her research began in 2006, when she was working on projects for Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) and Institute of Social Studies Trust (ISST) in rural hamlets of Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh. While investigating questions “about their employment and working conditions” she sensed a disinterest on their part. After all, they had answered these questions so many times before, she says. “In research, we are taught to employ different methods [to eke out information]... like ice breakers. So, I started asking people about their favourite actor, and lo and behold, everywhere I went, I met these giant Shah Rukh fans. The energy and enthusiasm when talking about your favourite actor is much more, when compared to talking about your economic circumstances, which honestly can be quite depressing. We live very harsh lives in India, at least most people. I decided I will give energy to that [the conversations about Khan],” she says. Her pursuit was a revelation of sorts. “For the next six to seven years, as I was sent to different areas of the country, speaking to women fans about him, I realised the women were no longer talking about him. They were using him as a metaphor.”

Fandom, explains Bhattacharya, is not a “silly cultural activity”. “It actually is an economic activity… to follow the work of an artiste requires money, free time, access to markets, media, public space, and even a mobile phone. None of these things, women in India [especially in rural India], can claim with ease.” She learnt along the way that one of the ways in which Khan’s Indian female fans “flexed their economic independence was to buy a movie ticket or a television set, so that they could star gaze at their favourite actor”. He became a means to articulate their autonomy. Not to mention, a benchmark to critique masculinity.

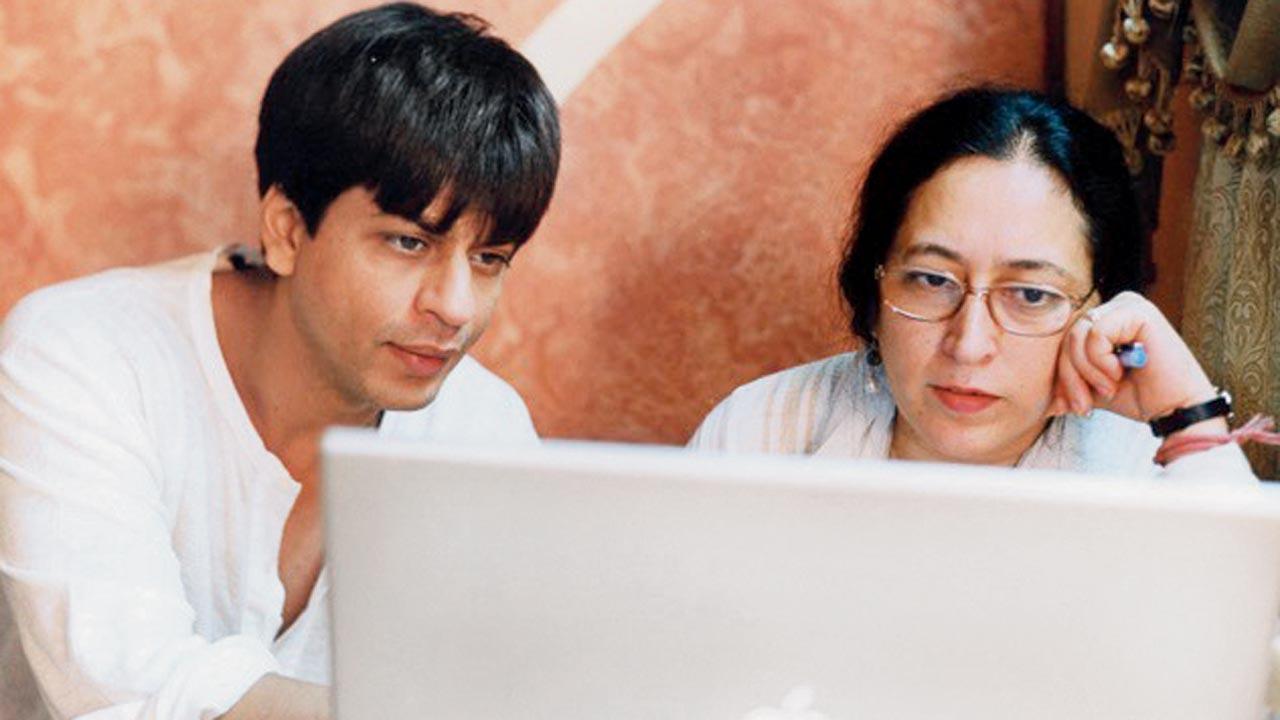

With director Nasreen Munni Kabir. Photographs by Peter Chappell. Pics courtesy/Hyphen Films, UK

With director Nasreen Munni Kabir. Photographs by Peter Chappell. Pics courtesy/Hyphen Films, UK

There is a line in her book that Bhattacharya harks back to: “As real men retreat, superstars gain more glory. An ideal man is found in fantasy. You scour the landscape of everyday life, but he is nowhere to be found.” The idea of Khan, the King of Romance as that “ideal” is what Indian women continue to celebrate even 30 years on.

Khan represents the softer, gentler kind of man, thinks Bhattacharya. Having had her own “heart smashed” in 2013, when she was in the midst of research, made her realise this more certainly than ever. “All the ordinary frustrations of not being seen and acknowledged, and all the labour that women are doing... [in Khan] they see a man who is acknowledging that, not just in his films, but also in his interviews. Through the interviews I conducted with the women, I realised that he is not just some silly celebrity crush... he is a well-thought out formulation of a man who helps in a kitchen, performs emotional labour, a man who accords a certain kind of dignity to women’s experiences, and the burdens our society places on us. He is a powerful icon not just because he is a remarkable personality of our contemporary age, or because so many people’s memories and life experiences are bound to him, but because he is a language. How many people become language?” she asks.

Writer-economist Shrayana Bhattacharya’s book Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh (HarperCollins India) uses the actor as a metaphor to explore the economic circumstances of women in post-liberalisation India. Pic/Shadab Khan

Writer-economist Shrayana Bhattacharya’s book Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh (HarperCollins India) uses the actor as a metaphor to explore the economic circumstances of women in post-liberalisation India. Pic/Shadab Khan

People’s love for Khan, argues Bhattacharya, is a serious social and cultural phenomena. Even his interviews to the media elicit emotion, she says, while narrating the experiences of her interviewees mentioned in her book. “When these women would feel lonely, they’d listen to his stories of loneliness and the struggles he had. And, they drew a lot of solidarity from that.”

Back in 2005, documentary filmmaker, TV producer and author Nasreen Munni Kabir and Peter Chappell gave fans a peak into the life of their most admired icon in a two-part film, The Inner and Outer World of Shah Rukh Khan. The documentary, in a first, showed us Khan, beyond the veneer of his stardom—the family man, diligent actor and live performer, committed smoker, who was dealing with the tragedy of losing his parents at an early age, and fighting the insecurities that came with success. Kabir, who is now in London, says that since 1988-89, she had been documenting a number of film personalities. “My choice for my documentaries were those who in my view were history makers and left an imprint on the industry.” Khan then was at the peak of his career with blockbusters like Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, Dil To Pagal Hain, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai and Kal Ho Naa Ho under his belt. “This was the time before Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, so your connection with the stars was still quite fictionalised. To see someone [like him] in their daily life, came as a revelation.”

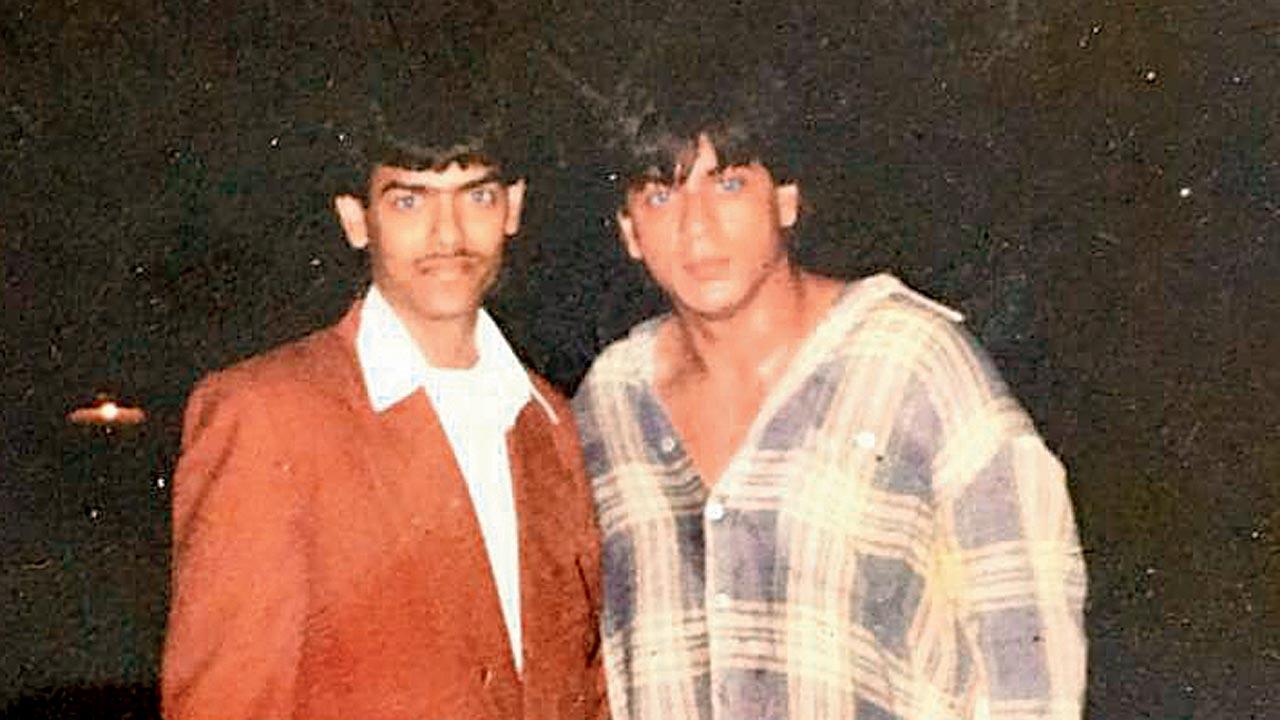

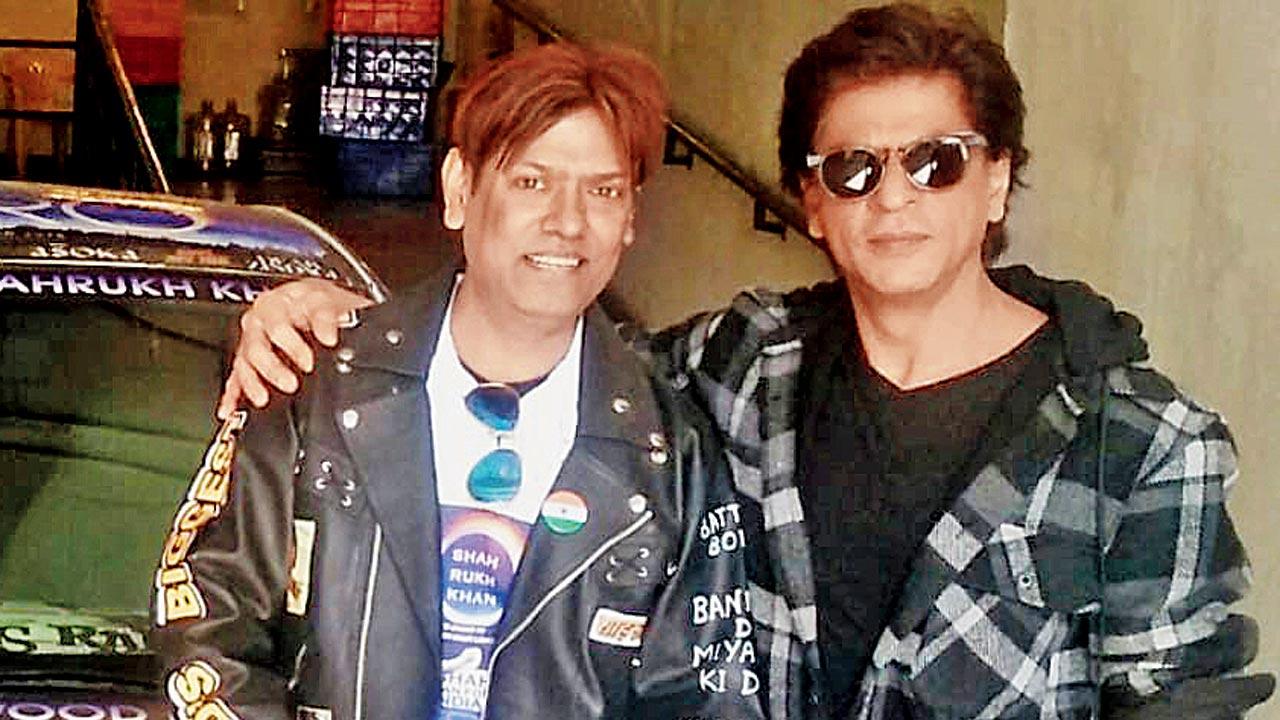

Vishahrukh wants to make a film with the actor so Vishahrukh Singh with Khan during their first meeting in 1996. me day

Vishahrukh wants to make a film with the actor so Vishahrukh Singh with Khan during their first meeting in 1996. me day

During the nine weeks she spent with him, Kabir saw a side of Khan, which was humbling—and that directly translated into how he came across in front of the camera. “He was a natural. He allowed you to film him, and was never really pretentious,” she remembers. “He was not vain. An actor, who is in front of the camera, would be constantly fiddling with his hair or checking himself out in the mirror... he was utterly the opposite of that. That was also the most endearing quality about him.” Kabir says when you interview Khan, you realise that “he is, who he is”. “And when he is with you, he is completely there. That particular capacity of being totally present, even in a fictional film, makes him so relatable.” That he is also intelligent means that he can analyse himself and his craft with great clarity.

Kabir admits that it is impossible to make an absolutely objective film about anyone, leave alone Khan, but the attempt here, was to understand what he meant to people. She remembers the time when she and Chappell went with the actor to New Delhi, where he visited the grave of his parents. “Even there, in the graveyard, he had all these people following him. They really didn’t think about that moment he needed with the memory of his parents. Peter and I, however, were at quite a distance from the grave. We chose a wide shot [to give him privacy]. I remember he said something very nice after that; he said, ‘you are not greedy. You could have been up my nose, but you chose to keep a distance’.”

To understand the reason why Khan continues to be loved among fans, Kabir says, you must go back to the 1990s, when the romantic hero was adored across generations. “Stardom doesn’t come before the films. The films [of the actor] have to match up first, and have to be lived by the fans for a certain number of years, before this actor is proclaimed a star.” In that, Khan had proved himself ably. “But there are some stars whose stardom is set in stone. So whether, the last film or the last two films are popular or not, nobody can shift them from their position. Shah Rukh is a bit like that... fans still have an attachment to him. He has become bigger than his films.”

Khan’s biggest fan, arguably, is Vishahrukh Singh of Lucknow. Vishahrukh’s fandom is both personal and public. He has christened his home Shah Rukh Palace, and his children, Simran and Aryan. His own birth name is Vishal, but he chose to keep Vishahrukh after director Subhash Ghai, who happened to see him on the set of Pardes, suggested that he take on the name of his favourite actor.

“My love for Shah Rukh ji only keeps growing,” he tells us over a video call. He is wearing a black T-shirt which has Khan’s name printed on it, and his brown hair is neatly parted in the middle, with strands inching close to his aviator glasses. It’s a “’90s SRK hangover,” we admit. Vishahrukh first saw Khan on Doordarshan, when he won acclaim for his roles in Fauji and Circus. “But, it was his character in the film Deewana [1992] that caught my attention. I had installed a music system on my bike, and I’d play two songs from the film and roam around every day... just like Shah Rukh ji.” After he got married, he and his wife Ruchi came to Mumbai to meet Khan. This was in 1996. “We didn’t even know how far Bandra was from Colaba, where we were lodged,” he remembers. At the time, Khan lived in Amrit Building on Carter Road. On someone’s suggestion, the couple even dined at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, as they were told that Khan visits a particular restaurant there after shooting. “We spent the entire evening there, and also incurred a huge bill, but Shah Rukh ji never came.” Vishahrukh finally came face-to-face with the superstar days later—it involved hovering around his building daily and befriending the security guards. He recalls creating a ruckus, when he tried to run behind Khan’s car, as it entered the gates. “I was screaming and wailing like a lover-boy for his attention. He had already read a letter that I had sent through the guard, where I had mentioned that I’d jump into the sea, if he didn’t meet me. So, he knew about me. He got out of his car, hugged and spoke to me. I was so emotional, that he had to remind me to get my camera out and take a picture with him.”

His love for Khan, he says, has only grown over time. Vishahrukh has since met the actor on several occasions, and each time, Khan has obliged him and the family. “He addresses my wife as bhabhi. When the world’s biggest superstar says something like this, who will not fall in love with him.”

In 2004, when Khan brought his fans to tears with his stoic performance in Kal Ho Naa Ho, where he is seen fighting a terminal heart condition, Vishahrukh was himself battling cancer. “I had bought the home I called Shah Rukh Palace around the same time... all this while I was undergoing chemotherapy. I drew strength from him and continue to do so,” says Vishahrukh, who has also launched a production house and an institute, where they teach dance and acting.

For Khan’s film, Fan (2016), he says the writers had reached out to him, to understand what obsessive fan worship can do. Vishahrukh was, however, disappointed with the character of Gaurav Chandna, the 20-something young man, whose world revolves around a mega movie star Aryan Khanna, based on Khan. “True fans won’t harm their heroes,” he tells us. His dream now is to make a film with Khan, titled Hum Bhi Hain Shah Rukh. “I have had many ups and downs in life, but Shah Rukhi ji has and always will remain a constant.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!