Making his debut at 60 with a show on the panchakanyas of Indian mythology, Jay Varma discusses his struggle with oils, being influenced by strong women and finding a voice different from his illustrious descendant

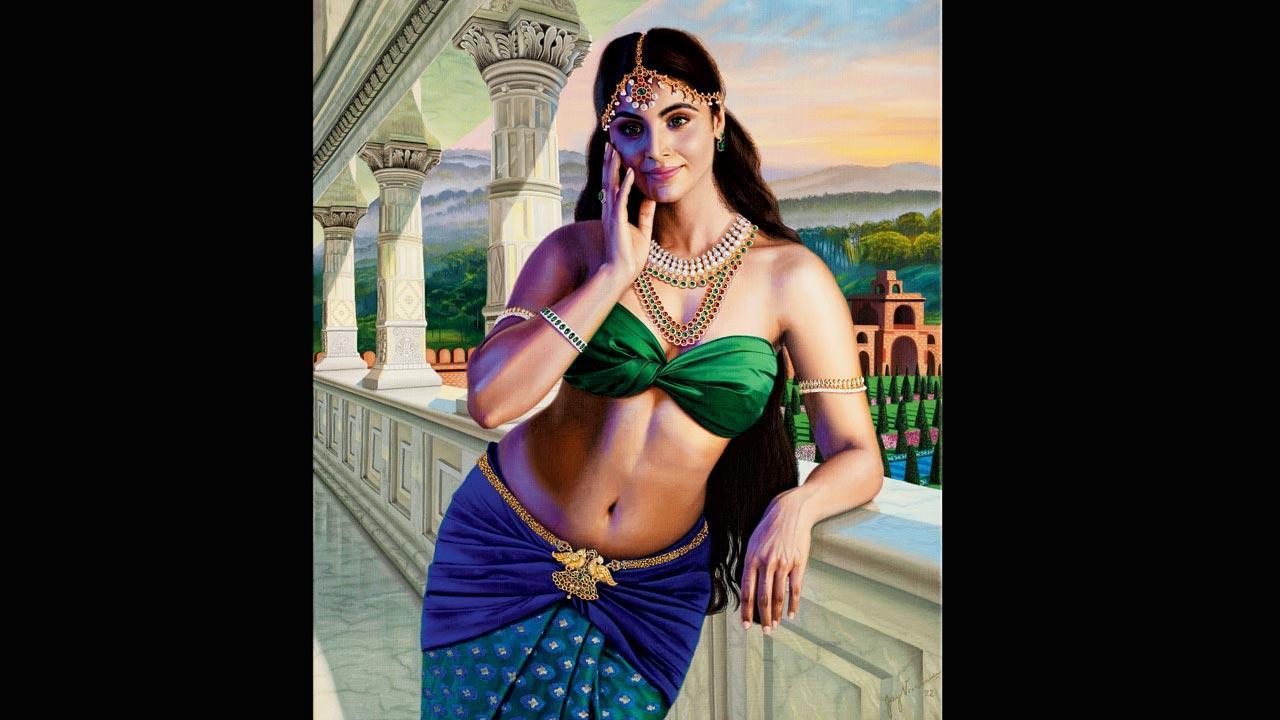

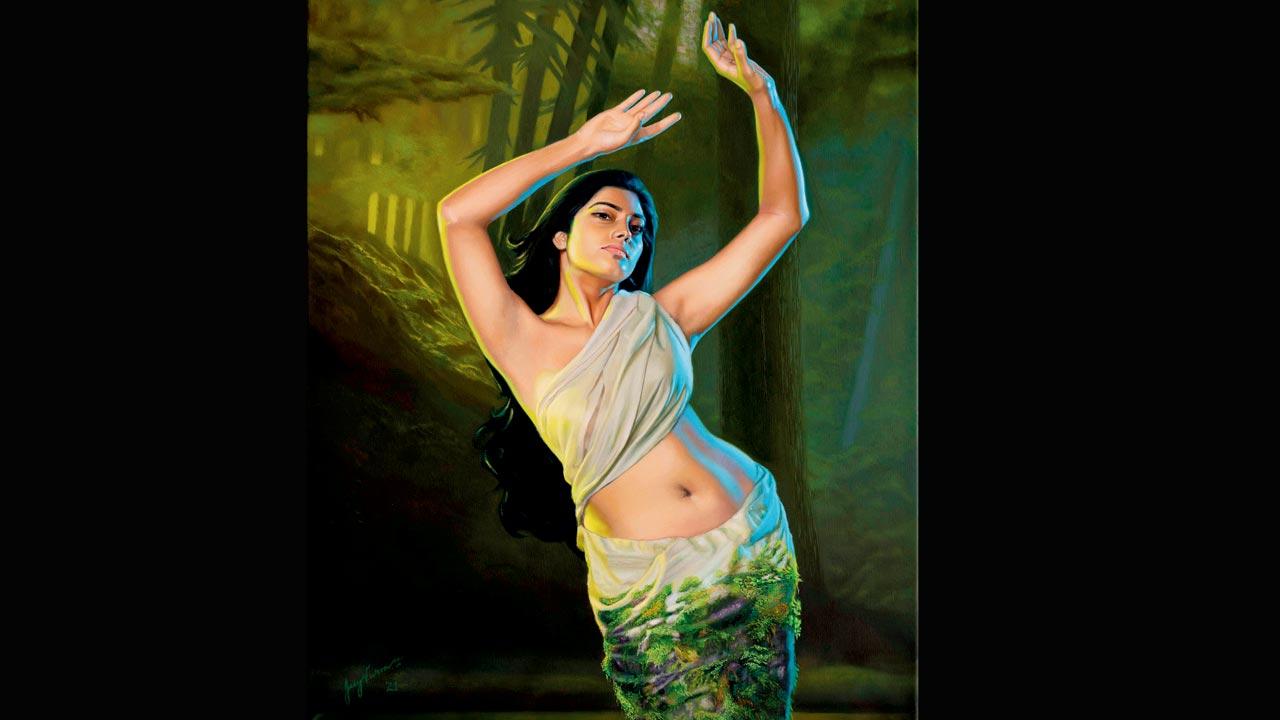

The artist’s new series, The Primacy of 5, sees him imagine the “panchakanyas” from the Ramayana and Mahabharata—Ahalya, Draupadi, Tara, Mandodari and Sita—as vastly different from what Raja Ravi Varma had envisioned

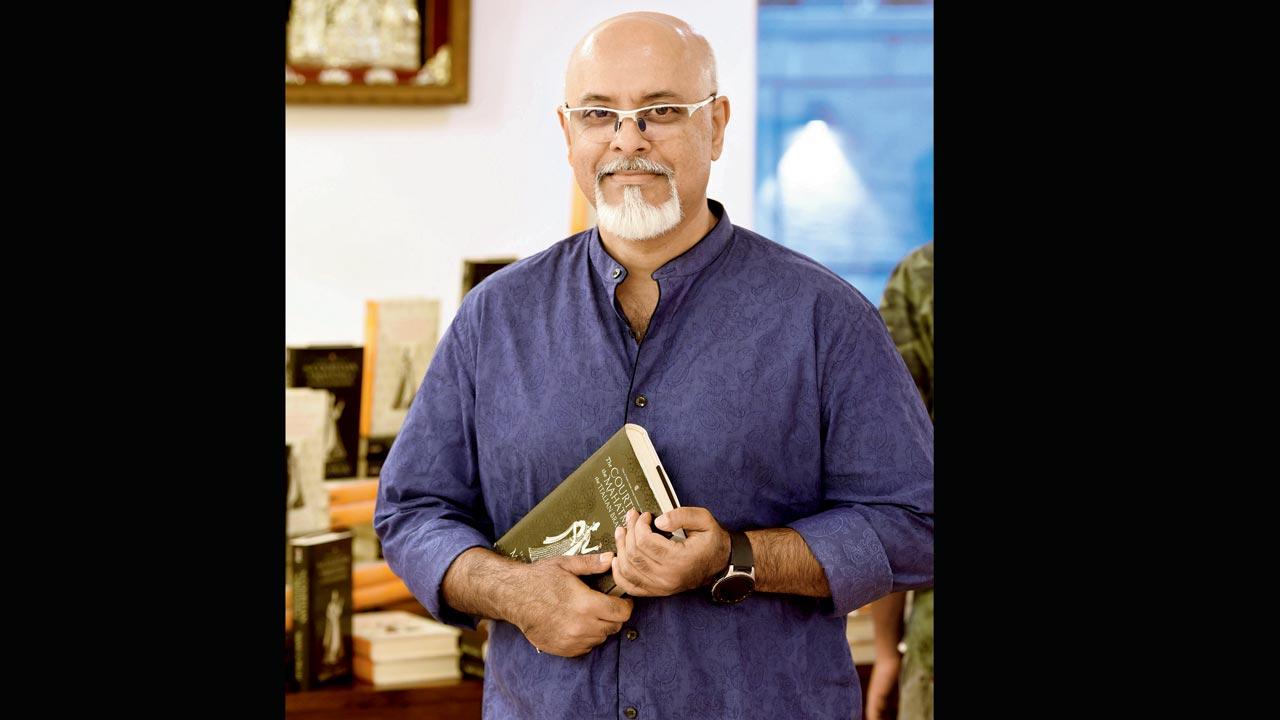

Self-Discovery is a process. Jay Varma will tell you how it can also be slow and consuming. The Bengaluru-based artist, who is a fifth generation descendent of the legendary painter Raja Ravi Varma, kept away from oils for a significant part of his life, because it “intimidated” him. Shying away from his talent—one that runs in the blood—he stuck to pencils mostly. It’s only in the last few years that something changed inside him, forcing him to pick up the paint brush. At 60, Varma is debuting with a solo exhibition, The Primacy of 5, at Bengaluru’s gallery g, which will showcase his oil paintings commissioned for private collectors.

The series, on display till April 30, sees Varma imagine the “panchakanyas” from the Ramayana and Mahabharata—Ahalya, Draupadi, Tara, Mandodari and Sita—as vastly different from what his ancestor had envisioned in his paintings, while still upholding the latter’s artistic legacy.

Sita

Sita

But more than Raja Ravi Varma, it was his great-grandmother, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi, the last maharani of Travancore (1924-1931), who is the force behind this show, he confesses. “She was an absolutely fantastic storyteller. She’d make us sit down, and tell us tales from epics in great detail, chapter by chapter. We heard tales featuring warrior kings, noble rulers, forest dwellers, demon lords... As kids, we could wish for nothing better. She definitely knew how to hold an audience. Sometimes, I almost believed that I was one of the characters,” says Varma, in a telephonic interview. He remembers hearing about Yudhisthira, the Pandava, whose feet never touched the ground when he walked: “I also began imagining that I was floating in the air!” These paintings, he says, are a tribute to her.

The female experience has undoubtedly been central to Varma’s understanding of the world, especially because the Travancore royals were matrilineal. His ancestresses were rulers, warriors, and political strategists. Art was also part of his everyday. Varma’s mother, Rukmini, made mythological canvases. “My furthest memory of her [as an artist] is from nearly half a century ago—it’s of her painting in the garage, which was at the back of our house. That image of her sitting in front of a canvas, applying oil colours with a paint brush, and slowly watching them come to life magically from abstract shapes to recognisable people and objects, is still fresh in my mind.”

Ahalya

Ahalya

It was she who first recognised 10-year-old Varma’s talent for drawing. “In those days, my great grandfather did a lot of photography, and he’d subscribe to annuals. Once, she brought one of his books, titled orld’s Best Photographs, and turned the page to a picture of a black athlete. It was just his torso. She got a couple of pencils, briefed me a bit about shading, and left me to my own devices. When she returned hours later, she was shocked with what I had done. That’s also one of my first art lessons.”

But for the longest time, he remembers attempting only pencil sketches—he found oil painting “inaccessible” and daunting. “I had a huge issue with oils and colours. I didn’t even attempt to try. I felt it was the purview of the privileged few—an exclusive club, if you may. The technical part of it is learnable of course, but you have to work very hard. I had to clear all my mental blocks. As a child, when you think you can’t paint, it does have a profound effect on your personality.”

Jay Varma

Jay Varma

Sometime in the early noughties, Varma went through a “traumatic and distressing” phase in his life, which drew him closer to art. “I started to think that I should have something to do, which will keep me occupied, and which I can do without getting bored and losing interest. It’s how I decided to learn to paint with oils. I spent some time abroad, but it was only in 2008 that I found the right atelier.” A few more years passed before art connoisseur and gallerist Gitanjali Maini, founder trustee of Sandeep and Gitanjali Maini Foundation and managing trustee of The Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation, offered Varma a grant for a three-year study programme at Studio Incamminati, a school for Contemporary Realist Art in Philadelphia. This was in 2015. “It’s been a long ride… not something that happened overnight. This [road to self-discovery] had its ups and downs, mostly downs really. At one point, I thought I couldn’t do it.”

In 2020, Varma began his professional journey with a family portrait of the Jung family. Nawabzada Omar Bin Jung was one of the individuals who patronised his

study programme.

His new series absorbs elements of Raja Ravi Varma’s work, only to find new language. Raised in the Victorian age, Ravi Varma’s women, draped in heavy gold-bordered sarees or sometimes even plain cloth, often appeared as damsels in distress: “his many Draupadi paintings show her rejecting Keechaka’s advances, being publicly humiliated by the Kauravas, or weeping as she serves as a maid”. Varma’s Draupadi, on the other hand, is a young woman, radiating desire and in the throes of love. “I wanted to give it a more contemporary feel, and make it relatable to the women of today. It was also important for me to give it context and depth, which would allow the onlooker to see the piece of art slightly differently each time they looked at it.” Draupadi, he says, was the first painting he started with in the series. “Both, the foreground and background are detailed here. When you look at Draupadi, you see her standing on the balcony of her father’s palace. This is also the moment when she sees Arjuna for the first time; she is so enamoured with his imperial bearings and charisma that she falls for him. When I made this image, the hope was that this was the first thing that people would see. There are symbols and metaphors within these paintings.” The clothes and jewellery that his women wear have also been coneptualised by him—“it required a lot of investment and research”.

Even when creating these works of art, Varma was aware that comparisons would be made with his more illustrious ancestor. “At the outset, there was this huge pressure to be able to produce a body of work that was respectable enough to stand on its own, regardless of whom it got compared with. That was a challenge for me, and also a huge weight,” he feels. “My style is different from that of Raja Ravi Varma’s, and so is my colour palette, and how I render my subject. But there is a fine line, and I will have to steel myself for any criticism that comes my way.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!