From boyhood, the CPI(ML) general secretary has dreamt of liberating the millions who are socially shackled. The party, once underground, grows too slowly to bring about enduring change

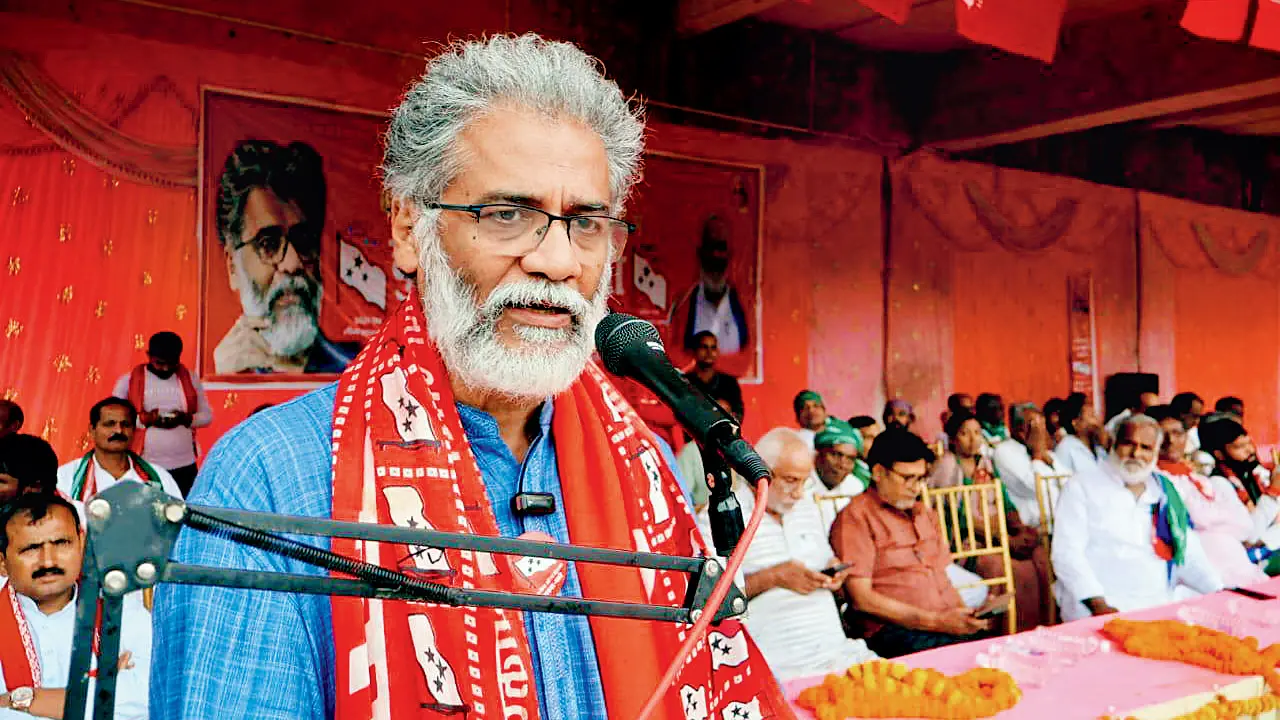

Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation General Secretary Dipankar Bhattacharya at a rally in Bihar. Pic/Bhattacharya’s Facebook account

Among the leaders spearheading the political parties in the Bihar Assembly elections, Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation General Secretary Dipankar Bhattacharya is decidedly an exception. He topped the 1979 West Bengal Higher Secondary Board Examination, secured a Master’s degree from Kolkata’s Indian Statistical Institute, scoring 65 per cent in Quantitative Economics and Planning, now known as econometrics — and still chose to join the CPI (ML), then on the cusp of transiting from being underground to participating in elections.

Among the leaders spearheading the political parties in the Bihar Assembly elections, Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation General Secretary Dipankar Bhattacharya is decidedly an exception. He topped the 1979 West Bengal Higher Secondary Board Examination, secured a Master’s degree from Kolkata’s Indian Statistical Institute, scoring 65 per cent in Quantitative Economics and Planning, now known as econometrics — and still chose to join the CPI (ML), then on the cusp of transiting from being underground to participating in elections.

He’s neither a political dynast nor has a wealthy background. His father, in fact, discontinued his college education to become a booking clerk with the Indian Railways because of financial constraints. Bhattacharya Senior was disappointed at his son’s decision to join CPI (ML) full-time, for a cushy job was his for the asking. “The bug of Naxalbari,” the CPI (ML) general secretary quipped, as an explanation for his choice.

He rewound his memory to the time he was at Alipurduar, located around 150 km away from Naxalbari, the site of the 1967 peasant uprising. Its tremors were experienced at Alipurduar, through stories of students joining the peasant rebellion, of brutal State repression and killings. In a junior class of a Railways school, at that impressionable age, he felt inspired, but also confused, particularly by a graffiti that screamed: ‘Turn the 1970s into the decade of liberation.’

He couldn’t fathom why with India celebrating, in 1972, the silver jubilee of its Independence, there was an exhortation for liberation. Liberation from what? Liberation for whom? His father explained to him that even though people enjoyed political rights, teeming millions were still socially shackled. Thus was the bug of Naxalbari born in him.

But even before the bug could burrow into him, he shifted after Std VII, in 1974, to the residential school of Ramakrishna Mission at Narendrapur, near Kolkata. Cut off from the stirrings of the world, the bug became dormant, resurfacing only at the Indian Statistical Institute. With minimum attendance not mandatory at the institute, Bhattacharya bunked classes to organise workers for the CPI (ML).

Yet it was in Bihar, not Bengal, where the party was in the thick of “war,” battling feudal landlords, who ruthlessly oppressed the poor, including wantonly preying upon women. ‘Jungle raj’ actually existed then, over which presided the strongmen from the upper castes. The CPI (ML) challenged them through a combination of armed struggle and democratic resistance, such as boycotting the harvesting of crops of oppressors and compelling them to “confess” to and eschew sexual violence. The shattering of the feudal arrogance catalysed the assertion of the backward castes, symbolised by Lalu Prasad Yadav’s rise.

In those blood-smeared decades, the CPI (M-L) didn’t participate in elections, but a rethink on this had begun even before Bhattacharya became a full-time activist in 1984. For one, Indira Gandhi’s defeat in the post-Emergency elections of 1977 underscored that people did have a say in Indian democracy operating “under the capitalist system.” The party’s boycott of elections only weakened their voice, deepening the disenfranchisement that the powerful carried out by intimidating voters and capturing booths.

For another, being underground implied the party couldn’t participate in social movements. “We realised we need to be where people were,” Bhattacharya said. To the people they went, first from the platform of the Indian People’s Front, which also comprised non-CPI (ML) leaders, in the 1989 Lok Sabha elections — and then under their own banner after the party formally came overground in 1992, in the backdrop of the rise of Hindutva and collapse of the Soviet Union.

Bhattacharya became the general secretary in 1998, at just 38. It was a challenge, for “it’s one thing to be a student activist, quite another to lead the party against feudal violence.” The CPI (ML)’s work among the rural poor has a slice of the Extremely Backward Classes and the Scheduled Castes to repeatedly vote for the party despite knowing it can’t come to power on its own.

They also largely transfer their votes to the CPI (ML)’s alliance partners. This was why the Rashtriya Janata Dal, the Mahagathbandhan’s lead player, gave 19 seats to the CPI (ML) in 2020, of which it stunningly won 12. It also brings to the Mahagathbandhan the energy of activism and a touch of gravitas, evident from Bhattacharya recently averting a meltdown of the alliance over allocation of seats.

However, these pluses can’t compensate for the CPI (ML)’s slow rate of growth, largely because of its rigid structure. You can’t become its member by paying a fee or giving a missed call. You must participate in party programmes, undergo probation before membership is confirmed — but that can still be revoked during periodic renewals. It’s a script for slowing growth, not speeding it up.

Bhattacharya countered my criticism, “In big parties, tickets are given to candidates backed by moneybags. Our candidates are from the rural poor and student leaders. The party’s rise must reflect the assertion of the poor.” I suddenly remember the tortoise won the race against the hare by moving slowly and doggedly. Yet you could also argue that the tortoise won only because the hare, in its arrogance, chose to sleep.

The writer is a senior journalist and author of Bhima Koregaon: Challenging Caste.

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!